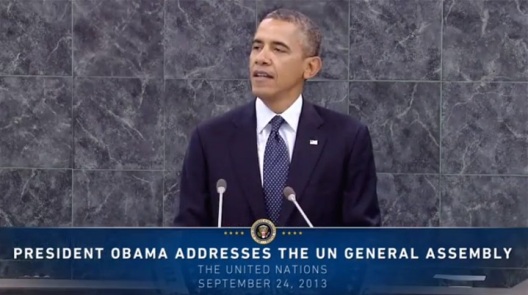

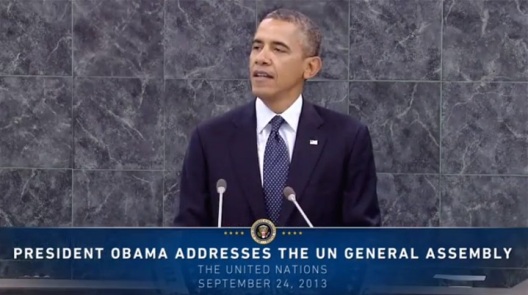

Using the forum of the United Nations General Assembly, President Barack Obama tried to present a coherent picture of the US approach to a region whose challenges will dominate the balance of his presidency whether he likes it or not. Indeed, the main headline of the president’s address might be something like “Obama Pivots to the Middle East.” Although the thrust of the speech clearly aimed at (and perhaps succeeded in) countering the impression of American disinterested ambivalence toward the turmoil of a troubled region, some of the language on Syria reflected more of the same.

Using the forum of the United Nations General Assembly, President Barack Obama tried to present a coherent picture of the US approach to a region whose challenges will dominate the balance of his presidency whether he likes it or not. Indeed, the main headline of the president’s address might be something like “Obama Pivots to the Middle East.” Although the thrust of the speech clearly aimed at (and perhaps succeeded in) countering the impression of American disinterested ambivalence toward the turmoil of a troubled region, some of the language on Syria reflected more of the same.

On the plus, side the president said some things that are obvious, and yet needed to be said. Referring to the chemical massacre of August 21 the president noted, “It’s an insult to human reason and to the legitimacy of this institution to suggest that anyone other than the regime carried out this attack.” There should be no doubt that the president knows who and what he is dealing with when he engages with Vladimir Putin. “It’s time for Russia and Iran to realize that insisting on Assad’s rule will lead directly to the outcome they fear: an increasingly violent space for extremists to operate.” Actually, Putin wants Assad to prevail so he can claim to the world that Russia successfully stands by its friends, even the war criminals among them. And Iran needs Assad for one thing: a physical link to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Neither Putin nor the Supreme Leader loses sleep over Syria’s fate except when their respective bottom lines are challenged. Still, it was good for the president to reiterate the inadmissibility of continued Assad rule in Syria.

In a passage no doubt reflecting an essential part of Barack Obama’s worldview, the president illustrated concisely a crucial part of his Syrian dilemma: “And, as we pursue a [negotiated] settlement, let’s remember this is not a zero sum endeavor. We’re no longer in a Cold War. There’s no great game to be won…”

If only Mr. Obama were the sole or decisive voter on this high-minded proposition. Does he think that the president of the Russian Federation, the person insulting “human reason” and the legitimacy of the UN by denying the truth of what happened on August 21st, shares his view about the 21st century state of international relations? Does he believe that the Supreme Leader of Iran, a man who presides over a worldwide network of murder and mayhem, shares his enlightened view of how the world should work? Or was he trying to persuade the Putins and Khameneis of the world by assuring them that America has no interest in Syria “beyond the well-being of its people, the stability of its neighbors” and so forth? Would he expect such a reassurance to be believed or respected by the likes of Putin and Khamenei? If Russia and Iran carry Assad across the finish line, can the US credibly claim it did not lose and it does not matter because it never signed up for the game?

Indeed, the president felt obliged to state that “The United States of America is prepared to use all elements of our power, including military force, to secure our core interests in the region.” He enumerated the core interests in terms of confronting external aggression, ensuring the free flow of energy, dismantling terrorist networks, and tolerating neither the development nor use of weapons of mass destruction.

Will Bashar al-Assad interpret this as a green light to continue his campaign of massed artillery, aerial, rocket, and missile fires on residential areas so long as he holsters the chemicals? Does this explain Russia’s interest in getting chemical weapons out of the Syrian equation, and Assad’s apparent interest, to date, in cooperating? Is the president really willing to take military strikes off the table no matter the scope of the humanitarian outrage in Syria, so long as chemical asphyxiation is not involved? To quote Barack Obama in yesterday’s address, “should we really accept the notion that the world is powerless in the face of a Rwanda, or Srebrenica?”

Indeed, the president employed some misdirection to deflect criticism on this score. “I know there are those who’ve been frustrated by our unwillingness to use our military might to depose Assad…” No doubt there were individuals in the Syrian opposition hoping to be handed power on a silver platter. Yet those Americans who have urged this president to consider the use of military force to stop, slow, or mitigate the wanton slaughter in Syria have not counseled a military campaign to depose Bashar al-Assad. If destroying the dictator’s tools of terror were to have that effect, fine. But the president tabled a red herring for the edification of the General Assembly. And by so doing he did himself no favor by implying that any application of US military force would entail the explicit mission of deposing Assad.

The president expressed the worthy hope that “Our agreement on chemical weapons should energize a larger diplomatic effort to reach a political settlement in Syria.” This weekend Secretary of State John Kerry will be exploring precisely this possibility with his Russian counterpart. If Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov indicates Moscow’s readiness to intervene with Assad to stop the massed fires on civilian residential areas and implement the deescalatory and humanitarian steps Kofi Annan urged way back when, then there may be a way forward. Unless the slaughter stops there is no basis for Geneva. An opposition already whiplashed by the administration’s twists and turns cannot afford to show up for dialogue in Geneva with those raining shells and bombs on its putative constituents. There can be no Geneva unless the terror campaign stops, unless the opposition wishes to commit suicide and the US wishes to abet it.

The president’s remarks were followed by an announcement that a variety of Syrian armed opposition elements, ranging from the Nusra Front to some that had used the Free Syrian Army brand, were forming a new alliance and rejecting the Syrian National Coalition. This essentially slaps a press release (one welcomed by the Assad regime and its apologists) on a pre-existing situation and illustrates the point that the term “Free Syrian Army” is not, in and of itself, an adequate vetting filter for the provision of US lethal assistance. This development also helps to illustrate the mother of all unintended consequences in Syria: the rise of well-funded, Assad-regime abetted jihadist groups in the absence of a leading American role in determining who gets what in terms of external military assistance. The operational question now is whether this announcement will do what it appears intended to do: dissuade the Obama administration from moving effectively to arm, equip, and train units willing to fight for the preservation of something in which Assad and his enemies of choice have no real interest: Syria for all of the Syrian people.

Frederic C. Hof is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.