It was the first time on the streets that I was not met with aggression as I roamed around gathering signatures for Tamarod. I usually experienced distrustful glares or comments, angry remarks expressing how I was destroying the country or vows that I was not Egyptian and had no right to be on the streets campaigning.

Most remarkable though was, and still is, the increased participation and enthusiasm of citizens from all cross-sections of society. Down one street lined with mechanic shops, men sat smoking shisha and drinking tea as they proudly announced that they had already signed the Tamarod petition. One man brought 250 signed sheets that needed to be delivered to the campaign office. Another man, unable to copy out the numbers on his national identification card, had campaigners fill the form and he scribbled out his signature.

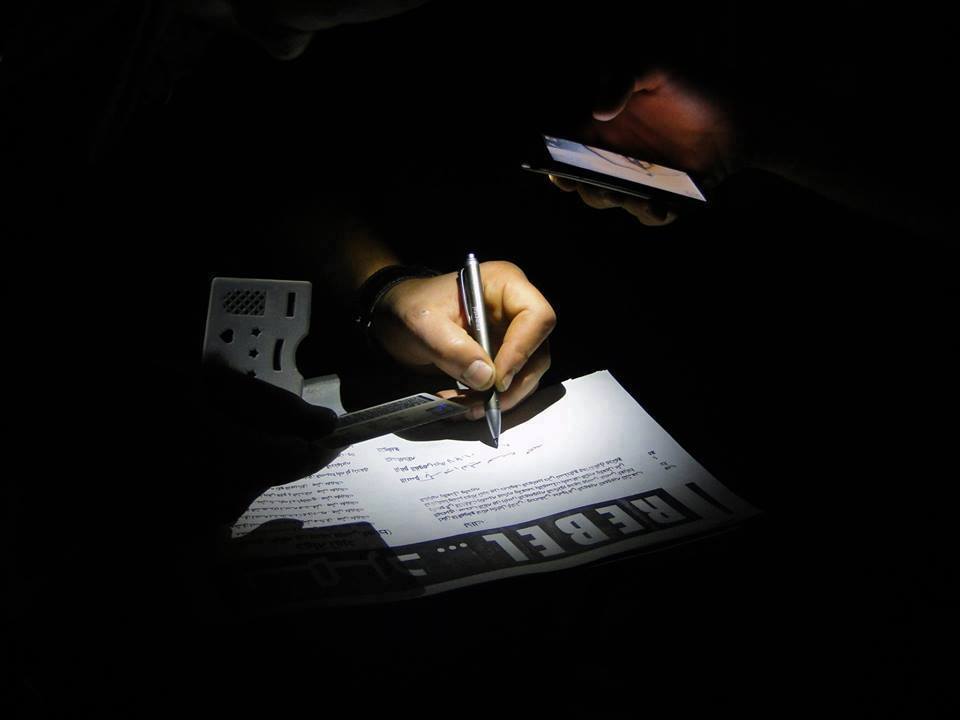

Now, one week leading up to June 30, the campaign announced that it passed its goal of 15 million signatures. Tamarod’s effectiveness stems from several factors. As a decentralized movement, it gained immense street popularity and redefined the concept of political leadership by empowering the average citizen to participate. Tamarod applications were made available online, allowing anyone to download, sign, and deliver them to the campaign office. One student made hundreds of copies to take to his university since no one from the campaign had showed up. Other activists gathered on Saturdays, roaming their neighborhoods gathering signatures. A few weeks into the campaign they launched online submissions, allowing Egyptians to sign the petition, no matter where they were. However, unlike past movements, the campaigners pushed into what historically are considered Muslim Brotherhood strongholds; South Sinai, several governorates in Upper Egypt, and Cairo slums.

Aside from the fact that it was and still is easy to participate in the campaign, the consequences of political inadequacy have been a positive catalyst for Tamarod. Inefficiency has slowly trickled down to affect the lives of most Egyptians, both rich and poor alike, leaving ‘withdrawing confidence’ from President Morsi an attractive option. As the first heat wave hit the country in late May, and electricity cuts hit highs for the summer, people’s frustration grew. Stores and restaurants shut down, losing customers, money, and occasionally were robbed, as the electricity went out every day for two weeks. A couple of weeks later, even after the government announced that the national supply of electricity outstripped the demand, electricity blackouts continue throughout the nation. Gas shortages force taxi and bus drivers to stand in line for hours to fill their tanks. Trash still lines the streets in the summer heat.

Dissatisfaction is not only visible in the increasing numbers of signatures announced by the Tamarod campaign, but also in two recent polls. Poll results show growing dissatisfaction with the president and the Egyptian leadership over the past two months. The Egyptian Center for Public Opinion Research (Baseera) reported a decrease in Morsi’s supporters from 46 percent to 42 percent in just one month. Additionally, over 5,000 face-to-face surveys by Zogby Research Services (ZRS) revealed that only 28 percent of eligible voters polled support Morsi, most of who identify with the Muslim Brotherhood. However, these results, while showing a significant decrease in support of Morsi, do not indicate a growing support for opposition, leaving a vast majority of pollers largely dissatisfied with the ruling Islamist party (74 percent) and the opposition leaders (71 percent).

It is unclear if Tamarod and the protest on June 30 will succeed in its goal of bringing about early elections and essentially everyone in the country is waiting in expectation to see what will happen. Unfortunately though, with increased aggression on the streets, many expect violence. Tamarod campaigners have already been caught up with clashes with members of the Muslim Brotherhood in several different governorates and in some cases their offices raided. In the official Tamarod campaign song, the young rappers recall the death of the martyrs they feel have died in vain, while some young revolutionaries express that they are not afraid to die for the cause. This is all a natural expression of a societal and political frustration, and in many ways an expected repercussion of past violence that most protestors have not forgotten.

Despite the tension on the streets, there are successes that have caught the attention of most Egyptians. The first success is that Tamarod has mobilized people en masse to be politically active once again. Activists have often wanted to see the first eighteen days of the revolution recreated and it has proved challenging to create new avenues for political engagement. Tamarod succeeded at preceding the June 30 protest with weeks of campaigning, signatures, and online advocacy. This is supported by an increasing number of political leaders and parties backing the Tamarod campaign, regardless of political leanings. Many opposition leaders and political movements have expressed support of the campaign, and announced their followers’ participation in the protests.

The public’s growing dissatisfaction with Morsi and his party could provide a significant boost to the opposition, despite its divisions and contradictions. However, like the spontaneous revolution that preceded it two years ago, the Tamarod campaign has once again proven that the Egyptian people need not wait for their ‘out-of-touch’ political leaders to represent their opposition to the status quo. While ElBaradei and other opposition leaders have indicated their intention to respond to the needs and expectations of this growing movement and the desired political change, they may well be swept up in the very same tide of anger and frustration that is driving the protest against Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. One question remains unanswered. What happens on July 1?

Amira Mikhail is the Egypt research intern with the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Photo: Tamarod Facebook Page

Image: Tamarod.jpg