It was not a cruel joke, and it appears the tragedy endures: on March 23, the Egyptian army’s research unit posted on its Facebook page a link to an online Google spreadsheet, titled “Registration form for Virus C and HIV/AIDS Patient”, for those wishing to book an appointment for treatment. A few hours later, the Facebook link was removed – but the Google form is still there.

It was not a cruel joke, and it appears the tragedy endures: on March 23, the Egyptian army’s research unit posted on its Facebook page a link to an online Google spreadsheet, titled “Registration form for Virus C and HIV/AIDS Patient”, for those wishing to book an appointment for treatment. A few hours later, the Facebook link was removed – but the Google form is still there.

To understand why this is a tragedy, a brief retrospective is warranted.

In late February, Egyptian media trumpeted the news that a military research team had succeeded in creating a diagnosis tool for Hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS, that would not require the patient having their blood drawn and had the same accuracy as traditional tests. The machine, named “C-Fast” and which looks like a stapler with a television antenna sticking out of it was dubbed a “mechanical divining rod”, and it identifies an infected patient by pointing at them. It is also remarkably cheap to manufacture, requires no source of energy to function, and is allegedly so sensitive it will start wagging like a happy dog’s tail if an infected patient is in the next room.

It all sounded quite impressive, particularly in a country where Hepatitis C has, according to the World Health Organization, reached an “epidemic spread” with 10 to 14 percent of the population infected, amounting to 8 to 10 million people. Though details of how it functions were unclear, it sounded like a real breakthrough.

Very soon thereafter, the public was blown away by another revelation: a second machine, also developed by the military researchers, could cure HIV, Hepatitis C, and according to various cavalier televised statements by members of the “research” team, could also cure any kind of virus, including the H1N5, and, in case one wasn’t sufficiently impressed, could also cure diabetes, skin diseases, and even cancer. And, to quote the official announcement video – it could also detect red termites in palm trees.

The name of this miracle device was “Complete Cure”, or “CC.” Any homonymic resemblance to the Minister of Defense’s name is entirely fortuitous.

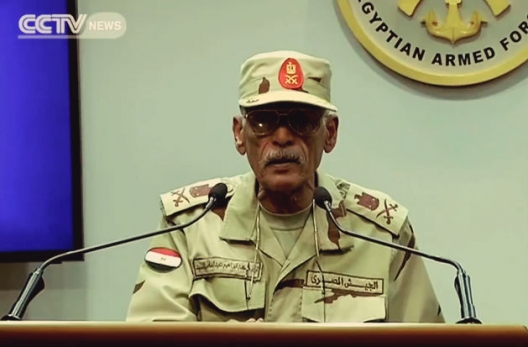

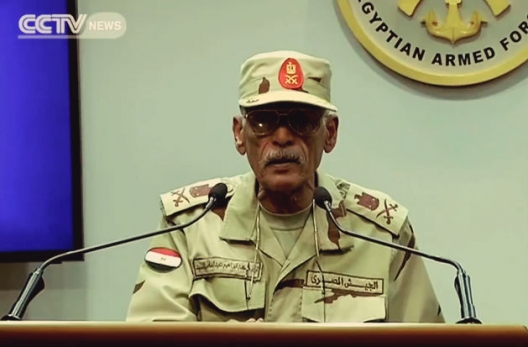

The official announcement of this discovery was not made at an international medical conference, but at a press conference dominated by uniformed officers, where one General Doctor Ibrahim Abdel-Ati, in too-new and slightly too-large military fatigues, presented his invention. Abdel-Ati also showed a video of himself telling a bedridden patient, “Your test results are flawless, you used to have AIDS, but now it’s gone,” to which the patient responds “thank God, thank God.”

And then came the part of the speech that has passed into cultural lore in Egypt, spawning endless mockery and countless memes. Abdel Ati said:“I take the AIDS from the patient, then feed it to him as kofta (meatballs) for nourishment. I take the disease, give it to him as nourishment. This is the culmination of scientific achievement.”

As the uniforms in the room clapped, and the presenter gave a clumsy military salute then left the podium, audiences at home blinked in disbelief. They looked at each other to confirm what they had just heard. Many checked the channel they were watching lest it were a prank.

They then took to social media, and “Koftagate” was born.

As the presentation was mercilessly mocked for its form, the content was also being dissected by scientists. The President’s scientific advisor Essam Heggy said it was a “scientific scandal.” MIT virologist Islam Hussein fulminated for days on Facebook at the absurdity of the claims made by Abdel-Ati and his team, ultimately producing an 80-minutes YouTube video in Arabic to refute the invention in an apparent attempt to avenge the entirety of science and logic, which were being trampled. After discussing the shoddy science behind the ‘invention,’ he pointed at the absence of clinical tests, medical proof, or patents backing the claims. Journalists also conducted similar investigative work and found a 2010 patent submission for the diagnosis tool under different names; Abdel-Ati’s never turned up, and none of the senior army physicians interviewed knew of him or his work.

At the same time, the history of the “General Doctor” was also combed through. He is, it turns out, neither a General nor a Doctor; the rank he was awarded by the Army for his work and the title he seemingly awarded himself, in an attempt to distance himself from some deeply suspicious herbal treatments he’d contrived, out of a rental apartment in the South of Cairo. Lawsuits had been filed against him; and in at least two instances he had been sentenced by a court.

But despite all the mounting evidence, many in the state-owned and state-aligned media, along with their various cheerleaders, are defending the ‘discovery’, heaping all-too-familiar accusations of treason over the skeptics. Abdel Ati refuses to answer questions about his medical training and background and stating that Army hospitals will start diagnosing and treating people as of the coming June 30 – the first anniversary of the massive protests that paved the way for the military to depose former president Mohamed Morsi.

We are not discussing a moon landing or even a theoretical physics breakthrough, with little or no immediate life repercussions. This purported medical discovery deeply concerns millions of Egyptian families, with 165,000 new cases yearly – 70 percent of which are related to the poor healthcare system. And while many were mocking Abdel-Ati and his AIDS-flavored meatballs, millions of others were hugging in joyful disbelief and falling to their knees in prayer, thankful that the suffering of their loved ones would come to an end. It’s possible that the unsubstantiated and breathless defense some have been mounting was probably born of despair: they believed it, and consequently it must be true. Anything else would simply be too painful.

Come June 30, my fear is that far too many will go to military hospitals, and will be sent home uncured. Or, worse—be told they are virus-free when they are not.

And until that day I shall pray that I am wrong, because the disappointment which will be inflicted upon millions whose hearts will sink as they realize that the suffering of their parents or children is far from over, and that this disease will probably take their lives, is terribly cruel. False hope is a terrible affliction for a doctor to give. Giving false hope to millions should amount to a crime. And that latest posting, which announced the opening of the waitlist for treatment, means that the army is set on pushing through with this charade.

This is more than a political blunder. This is a national tragedy. And if it plays out the way it seems that it will, than this stab to the heart of the most vulnerable, would be unforgivable.

Mohamed El Dahshan, an economist and writer, is a non-resident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.