It would seem that the struggle for power and legitimacy between the political forces, the revolutionary youth movements and the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) in Egypt has shifted from the squares and streets of the capital city, to events in history. The conflict has multiplied, moving from an attempt not only to control the present and shape the future, but to a new battle over things already past. At the heart of this conflict is the legitimacy of the army’s revolution in July 1952 versus the legitimacy of the people’s revolution in January 2011.

With the lead up and in the aftermath of the celebrations, an ongoing debate that clouded the revelry of the sixtieth anniversary of the 1952 Revolution has been about the movement’s original goals. The revolution’s six goals included the elimination of feudalism and capitalist imperialism, and the establishment of a real democracy, one ensuring social justice for its people. Many of the goals of the revolution were achieved, and in a timely manner, but after six decades, Egyptians took to the streets, igniting a revolution on January 25, 2011, in the name of those very same goals – for a lack of social justice. Egypt revolted against former president Hosni Mubarak, who viewed his rule as a legitimate extension of the 1952 revolution.

Many, among them the Muslim Brotherhood and the April 6 Youth Movement, believe that the January Revolution, viewed as the ‘People’s Revolution’ has eliminated the legitimacy of the 1952 Revolution, and so there should be no room for celebrating the failure to achieve basic goals in almost 60 years.

By political science standards, the July Revolution is no revolution at all – but rather was a military coup, simply due to the lack of the participation of the Egyptian people. While there exists an accusation that the 1952 Revolution led to the establishment of military rule, disguised in civilian clothing, it has remained a symbol of victory in Egypt, liberating the country from centuries of enslavement to other nations.

The 1952 Revolution succeeded in eliminating both feudalism and the ruling elite’s capitalist imperialism. Millions of Egyptians went from living their lives as impoverished farmers to land-owning citizens, their children receiving a free education. The revolution created a significant industrial foundation for the country, providing Egyptians with a good economic condition.

Fast forward 60 years, and through the 18 continuous months of the People’s Revolution, the relationship between SCAF and the revolutionary youth movements and many of the political forces has deteriorated, as a result of a chain of events which witnessed, among other things, the killing of protesters and 12,000 civilians standing trial in the country’s military courts. As a consequence, an association now exists between the army’s 1952 revolution and SCAF, leading to a flurry of events created on social networking sites, calling for Egyptians not to participate in celebrations for the anniversary, and instead to demand an end to military rule.

All participants in Egypt’s current political game are engaged in an attempt to grant themselves the mantle of legitimacy. The revolutionary youth, political forces, particularly those that are Islamist in nature, feel that the 2011 revolution has provided them with that mantle, one they associate with the general Egyptian population. At the same time, SCAF feels that the ‘Army’s Revolution’ legitimizes the army’s political role in the country, particularly as the army was instrumental in the establishment of the first Egyptian republic.

I believe that the conflict over the legitimacy of the January and July revolutions is part and parcel of the Islamist movement’s desire to take control of Egypt’s history, erasing from the history books any achievements gained through the 1952 Revolution. This, in of itself, is a test for President Mohamed Morsi, one in which he has to prove that he is a president for all Egyptians, and not a Muslim Brotherhood president who views the 1952 revolution in the context of a defeat for the organization.

While Morsi has relinquished his 33-year membership with Muslim Brotherhood, his political leanings are still clearly aligned with the group. When taking an informal oath in Tahrir, Morsi made a veiled reference to the 1960s, interpreted by many as a reference to the arrests and torture of Muslim Brotherhood members at the hands of then-President Gamal Abdel Nasser, the very symbol of the 1952 revolution. The treatment of the Muslim Brotherhood at the time is a clear explanation for their apathy and indifference to the 1952 Revolution.

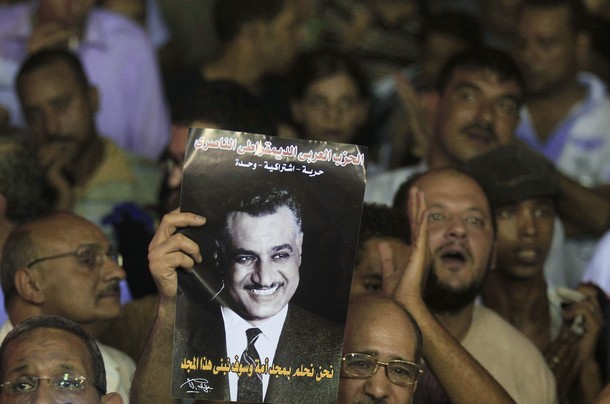

A number of political factions, among them leftists and Nasserists, as well as pro-SCAF citizens, took to the iconic Tahrir Square, a symbol of the January Revolution, on July 23 in celebration of the anniversary, amid chants of the now famous phrase, ‘The army and the people are one hand’.

Many of them were left feeling that the call by Islamist and some liberal political forces not to participate in the celebration was an attempt to change the course of history. They believe that Islamist political parties are devoted to their own historical presence, which goes far beyond the 1952 Revolution, particularly since Islamist political factions are dedicated to a project that goes against the Pan-Arab unity project adopted by the 1952 Revolution. Leftist leaders I talked to stressed the point that the Islamist project depends on the unity of Muslims and Islamic nations, rather than focusing on nationalism, as Nasser’s project did.

That said, the Muslim Brotherhood stressed the fact that participation in the 1952 Revolution celebrations was not discussed in any of meetings held by the organization’s leaders. Dr. Mahmoud Ghozlan, the Muslim Brotherhood’s official spokesman, said that the group is primarily concerned with the success of the January 25th Revolution, and are not preoccupied with issues relating to history.

The Egyptian streets are home to varying points of view regarding the 1952 Revolution. Some prescribe to the notion that it was a military revolution, and that January’s 2011 Revolution has overshadowed it. Others view the 1952 Revolution as a revolution of the people, carried out by way of the army, and so it should retain its legitimacy.

Speaking with people in the street, I was struck by fact that the popularity of the 1952 Revolution seemed to outweigh the popularity of the 2011 Revolution. This appears to be due to the fact that Egyptians enjoyed an immediate and welcome change as a direct result of the revolution. This stands in stark contrast with the January uprising, which for the most part has had no positive outcome, but rather has been followed by a painful period.

The 2011 ‘People’s Revolution’ is in need of real and tangible achievements on the ground if it is to replace the 1952 ‘Army Revolution’ in the hearts and minds of the Egyptian people as the legitimate uprising of the nation. Following 1952, many Egyptians reaped the benefits of a revolution that they did not undertake themselves, whereas in 2011, while they took to the streets, their voices and willpower playing an integral role in the uprising in Tahrir Square, they have yet benefit from it in any way.

Haitham Tabei is a special correspondent for the Washington Post and Asharq Saudi newspaper in Cairo, he previously worked as a journalist at the London-based newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat and as a political researcher with the Egyptian Council for Foreign Affairs.

Photo Credit: AP

Image: 610x_111.jpg