Over the past three decades, the tiny, wealthy Gulf emirate of Qatar has become one of Japan’s most important Middle Eastern partners. Driven by Japan’s demand for steady access to hydrocarbon resources from a reliable and stable partner and Qatar’s large-scale projects in preparation for the World Cup in 2022, the energy and construction sectors continue to dominate bilateral trade. However, in recent years Tokyo-Doha relations have expanded in financial, security, educational, and diplomatic spheres.

Over the past three decades, the tiny, wealthy Gulf emirate of Qatar has become one of Japan’s most important Middle Eastern partners. Driven by Japan’s demand for steady access to hydrocarbon resources from a reliable and stable partner and Qatar’s large-scale projects in preparation for the World Cup in 2022, the energy and construction sectors continue to dominate bilateral trade. However, in recent years Tokyo-Doha relations have expanded in financial, security, educational, and diplomatic spheres.

Since establishing diplomatic relations in May 1972, Japan and Qatar have developed strong ties in the energy sector. Japan played a key role in the international consortium developing Qatar’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry in the 1990s. The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster heralded a new era of bilateral cooperation. Japan shut down its nuclear plants, which had previously accounted for nearly one-third of domestic electricity production, making it increasingly reliant on Gulf energy imports to meet its needs.

Tokyo and Doha are arguably equally dependent on one another. As the world’s top LNG exporter, Qatar is Japan’s second-biggest LNG supplier (behind Australia) and Japan is Qatar’s top export partner. The Gulf Arab emirate is also Japan’s third largest oil seller (behind Saudi Arabia and the UAE), accounting for 11 percent of Japan’s oil imports, and its fourth biggest import partner. The bilateral trade, however, is markedly imbalanced. In 2013, Qatar exported $37.2 billion in energy resources to Japan, while Japan exported only $1.32 billion to Qatar, primarily in the automotive, electronics, and machinery sectors.

Sliding oil prices have taken a toll on Qatar’s state finances, causing Doha to run a deficit this year (estimated at $12.8 billion) for the first time in 15 years. Compared to other GCC states, however, Qatar is weathering the storm of cheap oil relatively well. This is largely attributable to Qatar being less dependent on oil for revenue than the other five GCC members. Qatar’s reliance on LNG (of which prices are only loosely correlated to oil prices) has left the emirate’s fiscal state more stable largely due to the long-term LNG contracts with Japanese companies including Japan’s Chubu Electric, Tokyo Electric Power, Kansai Electric, and Marubeni. Companies from other Asian countries have also signed long-term contracts with Qatar, helping the Gulf Arab state secure revenue during this period of instability in global energy markets. But Japan is Qatar’s most important trade partner and top LNG market; South Korea and India rank second and third, respectively.

Japan’s Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida visited Qatar last October to boost bilateral relations in economic and diplomatic spheres. His spokesman described Qatar as “very important for the stability of the Japanese economy,” adding that the Gulf country is “able to play a very active diplomatic role in these issues in this region, and so it is very valuable for [Japan] to exchange views on regional issues.”

With a sovereign fund valued at $256 billion, the wealthy GCC country can borrow from foreign banks rather inexpensively due to favorable interest rates and other contractual agreements. This is advantageous for Japanese financial institutions, including Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Mizuho, and Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp. These three financial companies, along with Qatar National Bank, Deutsche Bank, and Barclays, arranged a syndicated five-year loan (valued at $5.5 billion) for “general business purposes”, which Qatar closed in January. Earlier this year Mitsubishi Heavy Industries-led consortium secured a $61.5 billion order to construct a subway in time for the World Cup in 2022. Other major Japanese firms investing in Qatar, which include Thales and Hitachi, will construct a subway, a signaling system, a large commercial facility, and provide train maintenance in prepration for the event.

As Qatar and other GCC states are major arms markets, Japan has an advantage over lenders in Europe, where financial transactions on weapons carry more political risk and impose greater pressure on governments due to public opinion and corporate social responsibility. Last year, Qatar made a $6.8 billion down payment on Rafale fighter jets and missiles with funds borrowed from Japanese banks. As Qatar contributes to both the ongoing US-led campaign against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS or ISIL) and the Saudi-led one against the Houthi rebel movement and loyalists of former presdient Ali Abdullah Saleh in Yemen, Japan will likely continue to find Qatar a lucrative country for arranging arms deals with its major financial firms.

After the Fukushima disaster, Doha officials established the Qatar Friendship Fund, which donated $100 million to Japan for reconstruction projects. Additionally, Qatar has opened a Qatar Science Campus (QSC) in Japan’s Sendai City and a Qatar Sports Park in Shirakawa. Both ventures are consistent with Qatar’s tradition of utilizing its wealth and vast energy resources to achieve enhanced prestige within the international diplomatic arena. From as early as 2009, Japan has also supported Qatar’s diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict in Darfur within the framework of the 2011 Darfur Peace Agreement (aka the Doha Agreement), which the Sudanese government and the Liberation and Justice Movement signed in July 2011.

Challenges Facing Japanese-Qatari Relations

Despite this profitable relationship, Qatar faces competitors in the energy sector – chiefly from Australia and the United States. If Qatar is to maintain a completive advantage, it will likely have to lift the self-imposed moratorium on gas development (announced in 2005 and still in place) and boost its infrastructure investments in the emirate’s giant North Field. Saad al-Kaabia, Qatar Petroleum’s director of oil and gas ventures, stated that Doha imposed the moratorium, which was initially to be lifted in 2008, due to “a technical issue”, and extended the moratorium due to the risk of damaging the reservoir.

However, Qatar may soon lift the moratorium in the near future given the potential for more countries to enter the global LNG market between 2018 and 2023. As development is a timely process, Qatar might decide to begin exploiting the North Field before the end of 2017, according to energy analysts. As the North Field is acknowledged as the world’s lowest cost undeveloped gas field to exploit, international upstream firms will likely see a valuable opportunity to work with the Qataris as partners in this field’s development should officials in Doha decide to lift the moratorium. Within this context it is reasonable to question why Qatar has maintained this moratorium for over a decade. The answer likely stems from the fact that because the emirate has a small population and the world’s highest GDP per capita the Qataris have not seen a need to exploit the North Field yet.

Another important factor is Japan’s intention to restart 25 of its 48 nuclear reactors by the end of 2018, potentially diminishing the nation’s dependence on Qatar for LNG and oil imports. Certainly, Japan restarting these nuclear reactors raises questions about the country’s demand for Qatar’s increased capacity. Under such circumstances, there is a possibility that Qatar’s LNG exports will increase in other Asian markets such as China, India, and South Korea.

Often overlooked, Japan plays a quiet yet important role in the Middle East. Most discussion of Tokyo’s interests in the Gulf centers around Japan’s need for oil and gas, but Japan also exerts diplomatic influence by maintaining neutral, non-controversial foreign policies vis-à-vis the conflict-plagued region. For example, Tokyo has not taken sides in the Syrian crisis, but instead delivered a $60 million humanitarian aid package to the region in 2013 to ease the refugee burden imposed on Syria’s neighbors, most importantly Jordan. Japan maintains strong relations with Israel as well as Arab states and Iran. A decade ago, Tokyo initiated the “Corridor of Peace and Prosperity,” a “confidence building” initiative aimed at improving Arab-Israeli relations through the establishment of an independent Palestinian state which enjoys prosperous relations with both Israel and Jordan.

For this reason, many in the region view Japan as an important economic partner, which does not bring political baggage to the region. According to a BBC poll, only 14 percent of Saudis and 5 percent of Iraqis have negative attitudes toward Japanese influence (with positive ratings for Japan in those two countries at 42 percent and 54 percent, respectively), underscoring how negative attitudes toward Japanese influence are far less prevalent among these two countries’ citizens than they are toward France, Russia, the US and the UK.

From the Japanese perspective, Qatar represents a steady partner in a region beset by political unrest and turmoil. “Cautious optimism is the key concept for all our operations. Qatar is a symbol of steadfast actions.” These were the words of a Japanese business executive with decades of experience in the MENA region.

Qatar and Japan, although located on opposite sides of the Asian continent, maintain a deep relationship rooted in pragmatism and vital national interests. As a resource-poor country with the world’s third biggest economy, Japan is thirsty for foreign energy sources. Yet like other Asian nations dependent on foreign sources of oil and gas, Japan is vulnerable to the risks of growing geopolitical instability in the Gulf which threaten its steady access to a steady supply of hydrocarbon resources. Although this has prompted officials in Tokyo to develop deeper energy relations with gas-rich states outside the Middle East, Japan will remain invested in Qatar as the world’s leading LNG exporter and the Gulf region, from where Japan imports 80 percent of its oil and more than one quarter of its natural gas. At the same time, Qatar’s astonishing economic growth of the last two decades is largely attributable to the emirate’s ‘Look East’ strategy and its sale of LNG and oil to Asia, the destination for 80 percent of Qatar’s LNG exports. It is only logical to conclude that two countries so dependent on each other will continue working together for the foreseeable future to strengthen bilateral relations.

Cinzia Miotto is a Gulf analyst based in Saudi Arabia. Giorgio Cafiero is the CEO of Gulf State Analytics.

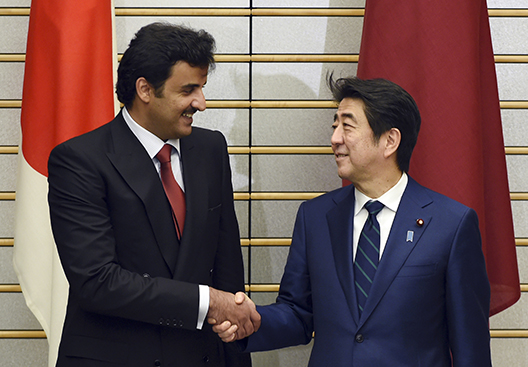

Image: Qatar's Emir Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al-Thani (L) is greeted by Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe before their talks at Abe's official residence in Tokyo February 20, 2015. (Toshifumi Kitamura/Reuters)