Turbulence seen across the Middle East and North Africa has caused most observers rightly to see Tunisia as the last best chance for a democratic outcome to the 2011 Arab Spring. While it is right to speak of the “Tunisian exception” relative to the high degree of dysfunction seen elsewhere though, the fragility of Tunisia’s transition should not be underestimated.

Turbulence seen across the Middle East and North Africa has caused most observers rightly to see Tunisia as the last best chance for a democratic outcome to the 2011 Arab Spring. While it is right to speak of the “Tunisian exception” relative to the high degree of dysfunction seen elsewhere though, the fragility of Tunisia’s transition should not be underestimated.

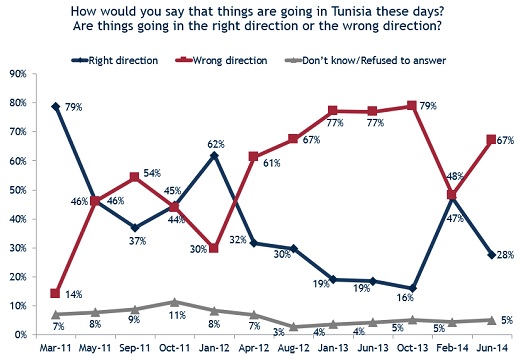

A February 2014 public opinion poll conducted by the International Republican Institute (IRI) revealed the close link between progress on the country’s democratic transition and Tunisian attitudes towards key issues like the economy. Conducted shortly after the passage of Tunisia’s new constitution, a considerable upward trend can be seen in those saying the country is moving in the right direction (from 16 to 47 percent). A similar upward trend is seen in Tunisians saying they can afford things like new clothes and eating out at restaurants (from 17 to 33 percent).

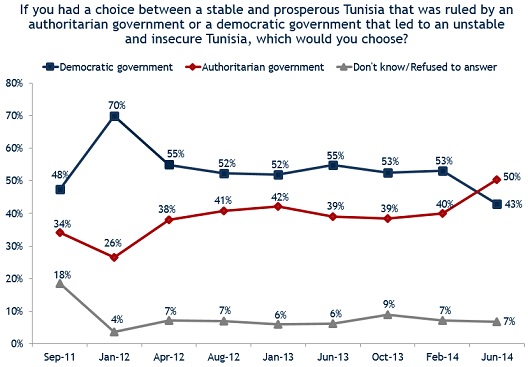

Fast forward four months to an IRI survey conducted in June and a concerning downward trend is seen. Those saying Tunisia is moving in the right direction sunk to only 28 percent, while those saying they can afford new things decreased from 33 to 24 percent. Likewise, Tunisians describing the current economic situation as very bad increased from 40 to 58 percent. Perhaps most troubling is the impact Tunisia’s economic challenges has had on perceptions about democracy. The June poll found that the perceived lack of democracy in the country increased with a record 39 percent saying that Tunisia is not a democracy at all. Worse, for the first time in IRI polling, those saying they prefer stable authoritarianism reached 50 percent, while 24 percent said it did not matter what form of government Tunisia has.

A partial explanation for the swings in opinion is that Tunisians, experiencing democracy for the first time, do not have realistic explanations about the pace their country will experience the tangible benefits of the transition. They also may not fully appreciate the damage done by the Ben Ali regime and the negative impact it has on Tunisia’s economic prospects now. At the same time though, the vibrant democratic culture that is emerging in Tunisia does not immediately equate with public confidence in political parties and leaders for which Tunisians yearn. In the June IRI poll, 70 percent said politicians in Tunis do not care at all about local problems (outside the capital Tunis). Sixty-five percent said that Tunisia’s political parties are only interested in power and personal gain.

Tunisia’s official campaign period begins October 4. Most of the major political parties have published their programmes; the equivalent of party platforms. But with over 100 parties and 1,300 registered candidate lists, Tunisian citizens can perhaps be forgiven if they have a difficult time distinguishing between political competitors. The Ennahda Islamist party, which captured the largest share of votes in Tunisia’s 2011 elections, may again have a slight advantage based on its use of religion to attract voters in much the way identity politics works in other countries. But the Ennahda-led government also alienated more secular Tunisians and was seen as being too slow by many in responding to Tunisia’s security challenges. It is not surprising then that 31 percent of Tunisians say they do not yet know for whom they will vote in parliamentary elections on October 26, while an additional 30 percent say they will not vote for the same party as they did in the last election. Like the other parties, Ennahda leaders must convince Tunisians they have a clear program for how they would lead the country, and be realistic about meeting the expectations they are setting.

There is plenty of reason to be cautiously optimistic about the next milestone in Tunisia’s transition. When compared to the rest of the region, the country is a bright spot. But enthusiasm for democratic progress fades when advances in the political transition are not matched with tangible benefits, especially economic benefits. As parliamentary elections approach, Tunisia’s political leaders must do a better job at managing the public’s expectations. This is critical for the campaign period, and will be especially important for the next elected government.

Scott Mastic is the International Republican Institute’s Director for the Middle East and North Africa. He visited Tunisia last week. IRI will send international election observers for Tunisia’s parliamentary and presidential elections.

Image: Ali Larayedh, former Tunisian prime minister and leader of the Ennahda Movement Party, gestures and stands among supporters waving national flags, in Tunis October 6, 2014. Tunisia's main Islamist party began campaigning on Monday preparing to face off with secular opponents and former regime officials in the second free elections since the North African state's 2011 uprising. (Photo: REUTERS/Zoubeir Souissi)