Twenty years after the Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon, Hezbollah faces host of challenges

The chain of events twenty years ago, on May 24, that would lead to one of the most significant moments in the Arab-Israeli conflict began in an unlikely manner. Two exiled residents of Kantara, a village lying just inside Israel’s occupied zone in south Lebanon, had slipped away from a memorial in the neighboring unoccupied village of Ghandourieh to visit their old homes.

Normally, crossing into the occupation zone on foot would have been tantamount to suicide. But they knew that the Israeli-backed South Lebanon Army (SLA) militia had abandoned its compound in Kantara days earlier as part of Israel’s plans to leave Lebanon for good. Sure enough, on arrival, they found the village unguarded and were greeted by a handful of startled elderly residents who had remained in Kantara during the occupation. Phone calls were made and soon an army of civilians was pushing through the lines of United Nations peacekeepers and following the road to Kantara. With Kantara liberated, the crowd pressed on north; initially, to the village of Qsair and, then, east through Deir Serian. By nightfall, they had reached the large village of Taibe, a mere two miles from the border with Israel.

This unexpected development stunned both the Israeli military and Lebanese militant group Hezbollah. Israel was preparing to depart Lebanon in line with a pre-electoral promise a year earlier by Prime Minister Ehud Barak that, if elected, he would “bring the boys back home” within a year of taking office. He hoped to achieve that goal by reaching a peace deal with Syria that would allow for an orderly withdrawal from Lebanon. That ambition collapsed in April 2000 when President Hafez al-Assad rejected a peace proposal that fell short of the Syrian leader’s expectations. Barak was left with no choice but to honor his pre-electoral pledge even if it meant withdrawing from Lebanon unilaterally.

By May 2000, the Israeli military was drawing down its forces ahead of the final pullout scheduled for July. Hezbollah, on the other hand, was preparing to mount a last offensive against the Israeli troops, determined that the world would see the occupying forces retreating under fire. The next morning, hundreds of former residents of the occupation zone gathered in the village of Shaqra and, despite the protestations of UN troops, began a march across the frontline to the village of Houla on the border with Israel. The Israeli army was powerless to stop unarmed civilians and it was all over two days later. The SLA collapsed, with some surrendering to the Lebanese authorities and others fleeing in terror with their families into Israel, fearing reprisals from the triumphant Hezbollah. The Israelis dynamited some of their positions and under a barrage of artillery fire pulled their forces out of Lebanon without incurring casualties.

It was the first time that Israel had yielded occupied territory through force of Arab arms alone. It was Hezbollah’s crowning moment and the group’s popularity in Lebanon and across the Arab and Islamic worlds had never been higher.

May 24 marked the twentieth anniversary of that historic event—the culmination of Hezbollah’s resistance campaign from the mid-1980s to oust Israeli troops from Lebanese soil.

At the time, Hezbollah was a small organization numbering some three thousand to four thousand full-time and part-time fighters. It had a small, but potent, parliamentary presence and it had the protection of neighboring Syria, which dominated Lebanese politics at the time. Hezbollah’s largest rocket had a range of only twelve miles, just enough to cross the occupation zone to spatter targets in northern Israel.

In the intervening two decades, Hezbollah has grown from a lean and focused military organization that used its rudimentary weapons and equipment to good effect, to today’s massive army of some thirty thousand trained fighters, many of whom have been battle-hardened in Syria. Its arsenal of rockets and missiles, including guided systems with 1,100-pound warheads, would not look out of place in a medium-sized European army. The wars in Syria, in Iraq against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), and in Yemen in support of the Houthis, have turned Hezbollah into Iran’s most dependable ally and force enabler. Perhaps, the ultimate accolade for Hezbollah is that Israel now considers the Lebanese group to be its gravest conventional military threat. Politically, Hezbollah is the dominant force in Lebanon. Hezbollah and its allies form the parliamentary majority and back the Lebanese government.

And, yet, despite this amassing of military might and political power, Hezbollah, paradoxically, has never faced such an array of challenges. In the twenty years since the Israeli troop withdrawal from south Lebanon, a whole new generation of Lebanese Shias have grown up with few tangible memories of the Israeli threat. It is becoming increasingly difficult for Hezbollah to sustain the anti-Israel resistance narrative to younger Shias, especially, those who do not live in proximity to Israel in south Lebanon.

Hezbollah promotes the notion of a society of resistance, where all elements of the community, not just the fighters, are in a state of constant war readiness and are committed to the cause. The party achieves this through speeches, parades, festivals, lectures, media propaganda, and study groups that begin in childhood and continue uninterrupted into adulthood and beyond. However, the last time Hezbollah fought Israel in a significant manner was fourteen years ago in the month-long war of 2006. Since then, Hezbollah has staged only seven overt military operations against Israeli forces. Instead, Hezbollah has been busy battling Sunnis in Syria and Iraq and assisting Yemen’s Houthis to confront a Saudi-led coalition. And, for many Lebanese Shias, it is not the threat of Israel that has been uppermost on their minds in recent years, but the rise of extremist Sunni groups like ISIS, which have staged several bombings in Shia-populated areas of Lebanon.

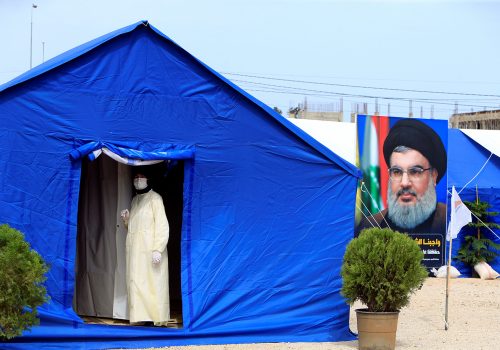

Then, there are the monetary difficulties brought on, mainly, by US sanctions against Iran and on Hezbollah’s financial supporters, augmented by the costs of running a war in Syria and paying salaries in an organization that has increased tenfold since 2006. So dire is the financial crunch, that, Hezbollah leader Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah made a public call for donations from party supporters in 2019.

Hezbollah’s military intervention in Syria on behalf of Bashar al-Assad’s government has destroyed the consensus of support it had earned among the region’s Sunni Muslims. When protests broke out in Lebanon in October 2019 against the country’s corrupt political elite and the worsening economic climate, the Shia duopoly of Hezbollah and the Amal Movement were among the targets. Shia protestors braved intimidation and threats from Hezbollah and Amal supporters to join anti-government gatherings in Beirut or stage their own protests in Shia-populated areas of the country.

Hezbollah’s internal cohesion is not as strong as it was when the party fielded only a few thousand fighters. The rapid recruitment process following the 2006 war and, especially, after it began deploying in Syria in 2012 has lowered the quality threshold of some recruits compared to twenty years ago, which has resulted in some internal corruption and indiscipline.

It is easy to picture Nasrallah in a contemplative mood, perhaps, nostalgic for a return to the party’s “golden years” in the latter half of the 1990s, when life was simpler. The fighters were focused and committed to the singular cause of ousting the Israeli army from Lebanese soil; they had the consensus and growing admiration of the Lebanese for its martial prowess; they were unencumbered with the grubby quid pro quos of Lebanese politics; they were untainted by the endemic corruption of Lebanon; and their resistance priority was protected by Syria. The Israeli troop withdrawal was a moment of victory for Hezbollah, but it also for the first time placed the party in a quandary with which it has had to wrestle ever since before a growing audience of critics: how do you justify a continued resistance when there is no occupation left to resist?

Nicholas Blanford is a nonresident senior fellow with the Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Image: Members of U.N. peacekeepers of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) sit in their vehicle at a lookout point in the town of Al Wazzani, near the Lebanese-Israeli border, in southern Lebanon January 5, 2016. REUTERS/Aziz Taher