The US military assistance program to the Lebanese Armed Forces must endure

One morning, in late May 2007, this author found himself in the garden of a small mosque that had been requisitioned by the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) on the edge of the Nahr al-Bared Palestinian refugee camp in north Lebanon. Several exhausted and bleary-eyed soldiers sat in the shade and quietly smoked cigarettes, while a major sat on a stool answering his two constantly ringing cellphones placed on an upturned ammunition box.

The soldiers were two days into a battle against a self-proclaimed jihadist group called Fatah al-Islam, which had taken root in the camp several months earlier. The fighting began when the militants attacked LAF posts surrounding the camp, killing seventeen soldiers; some of them were beheaded as they slept in their beds.

The LAF was ill-equipped and untrained for urban warfare on this scale. The soldiers in the garden carried a mix of M16A1 and AK47 assault rifles. Their body armor had no ballistic plates and their tin helmets dated back to the 1950s. The major’s main means of communication were the two cellphones.

The ever resourceful LAF up-armored civilian bulldozers using steel cages, metal plates, and sandbags to offer protection against Improvised Explosive Devices and snipers. Some of the LAF’s UH-1 “Huey” helicopters were rigged to carry five hundred-pound static aerial bombs that had been in storage since the 1960s. The pilot would fly directly above the target and release the bomb World War I style.

The battle lasted three months before Fatah al-Islam was finally defeated and driven from the Stalingrad-like rubble of the destroyed refugee camp. Over 160 soldiers were killed in the confrontation and more than two hundred militants died.

Fast forward ten years to August 2017, and the LAF was back in action—this time, against some six hundred militants of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) that were holed up in the barren mountains that straddle the border with Syria in north east Lebanon. This theater was wholly different compared to the cramped urban passageways of Nahr al-Bared, but the enemy was more numerous and deemed more formidable.

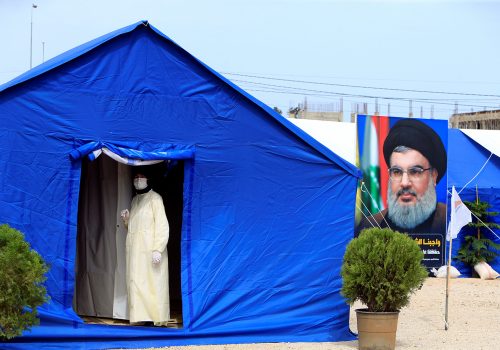

Lebanese Hezbollah had just finished a week-long successful offensive against the jihadist group Jabhat Fatah ash Sham whose stronghold lay in hills just south of ISIS territory. That fight had ended in a deal in which the surviving militants were bussed off to the rebel-held Idlib province in northern Syria. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah then announced that the LAF would take the lead in the fight against ISIS.

The LAF launched a carefully drawn-up plan that saw a combination of regular and special forces units adopt a pincer movement to close on ISIS fighters from the north, south, and west and force them east to the border with Syria. Missile-firing AC208 Cessna aircraft flew over the battlefield, directing laser-guided 155mm “Copperhead” artillery rounds onto ISIS hilltop bunkers and fortifications. In less than a week, ISIS was defeated and had retreated into a seven square mile area adjacent to the border with Syria. It was a stunning success that drew widespread praise from foreign military observers. A retired LAF brigadier general, who had helped devise the operational plan, later told this author that “two things won the battle: ISR [Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance] and precision munitions.”

What a difference a decade makes. In 2007, during the battle against Fatah al-Islam, the LAF had precious little precision munitions and ISR capabilities. The drastic improvement came from twelve years of foreign military assistance, primarily from the United States, which has provided over $2 billion in weapons, ammunition, equipment, and training since 2005.

The aforementioned foreign aid has turned the LAF into a more confident and competent military force that has earned the respect of the Department of Defense. Nevertheless, fifteen years of US commitment to the LAF could come under threat in the post COVID-19 era, as Washington potentially prioritizes plans to budget for measures to protect US forces against future pandemics. That could have implications for the continued military assistance program for partner countries like Lebanon.

The military assistance program already has been under fire for some time because of the perceived conciliatory relationship between the LAF and Hezbollah. That relationship is extremely complex and nuanced and defies black-and-white explanations. As two armies crammed into a tiny country, the LAF and Hezbollah engage in case-by-case deconfliction efforts. Some elements of the LAF have cooperative ties to Hezbollah, but there are many in the LAF that bristle at having to share national security duties with a non-state actor that draws its direction from Iran. And although Hezbollah has not opposed the LAF’s relationship with the US, it is quietly wary of the LAF’s growing capabilities. Hezbollah’s spoiler actions during the LAF’s campaign against ISIS in August 2017 were particularly revealing in this regard.

Hezbollah upstaged the LAF by independently launching its campaign against Jabhat Fatah ash Sham in July 2017, just, two days after then Prime Minister Saad Hariri had announced that the LAF would have that responsibility. When the LAF began its own offensive against ISIS two weeks later, Hezbollah media outlets repeatedly claimed the battle was being waged in coordination with Hezbollah and the Syrian army, even though the LAF fought independently. When it became clear that the LAF had triumphed and was poised to crush the last surviving elements of the Islamic State, Hezbollah stepped in to announce that a deal had been made in coordination with Damascus to allow the militants to escape to the Syria-Iraq border. During a visit to the battlefield on the first day of the ceasefire, a Lebanese soldier told this author: “We know [Hezbollah] wanted us to fail. But we didn’t.”

Lastly, Hezbollah held a victory parade in Baalbek to celebrate the defeat of Jabhat Fatah ash Sham, but, when the LAF planned a similar event in downtown Beirut in September 2017, it was abruptly cancelled two days beforehand. This author was told that Hezbollah had leaned on its ally, President Michel Aoun, to halt the event. The sight of a victorious LAF marching through the center of Beirut was, apparently, an optic that Hezbollah preferred not to see.

Other than for its competition with Hezbollah, maintaining US support for the LAF is increasingly critical as Lebanon undergoes its worst economic and fiscal crisis following the end of the sixteen-year civil war in 1990—a crisis exacerbated by the Coronavirus-enforced shutdown. The Lebanese lira, officially pegged since the mid-1990s at 1,507 to the US dollar, has plummeted since February on the parallel market, reaching LL4,000 to the dollar by April 27. Unemployment is soaring and businesses are shuttering every day. Banks have arbitrarily imposed capital controls, limiting the amount of money account holders can access and banning international transfers.

When the long-expected economic crisis began to bite in October 2019, Lebanese from across the country staged mass protests against the current cross-sectarian political leadership. Although the coronavirus shutdown ended the protests, they are beginning to re-emerge and are spurring violence as tempers flare and frustration mounts.

The LAF is the one state institution that can prevent chaos from taking over the country. If the LAF was to disintegrate, Lebanon would face a disastrous security situation, where Hezbollah would be the sole effective military force in the country. One option that the administration should consider is diverting some of the current funding to help pay the salaries of the LAF. The purchasing power of the Lebanese lira has declined and that will place great pressure on soldiers and their families. It could, down the road, lead to desertions—as happened in the civil war—with soldiers looking to find alternative means of employment.

Furthermore, if the US halted its military assistance program, there are other countries—most notably Russia—that may seek to fill the vacuum. Moscow has been signaling an interest in expanding its Middle East influence from Syria into Lebanon for several years, using the LAF as its primary vehicle. The LAF is now fully invested in US and Western weapons and equipment and is uninterested in acquiring Russian systems. But if the US funding dries up, it may have little choice but to accept whatever assistance is offered regardless of the sponsor.

The US military assistance program has been a solid success in Lebanon and the LAF deeply appreciates the partnership. That partnership must endure as Lebanon faces an ominous future.

Nicholas Blanford is a nonresident senior fellow with the Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Image: Lebanese army soldiers deploy in an attempt to open a road blocked by demonstrators during ongoing anti-government protests in Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon November 5, 2019. REUTERS/Mohamed Azakir