In yet another attempt to reinforce his administration’s counter-Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL) strategy, President Barack Obama has determined that the United States needs a small contingent of US ground personnel to enable the offensive capability of moderate Syrian opposition forces in northern Syria. As the administration explained during its rollout, the fifty special forces operators will link Kurdish YPG and Syrian Arab coalition forces on the ground with the US fighters and bombers circling above to pinpoint ISIS targets. Combined with a more intensive series of air strikes on ISIS positions in and around Raqqa, the introduction of special forces is designed to improve the fighting capability of local Syrians forces who have an incentive in driving the terrorist group from their areas.

In yet another attempt to reinforce his administration’s counter-Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL) strategy, President Barack Obama has determined that the United States needs a small contingent of US ground personnel to enable the offensive capability of moderate Syrian opposition forces in northern Syria. As the administration explained during its rollout, the fifty special forces operators will link Kurdish YPG and Syrian Arab coalition forces on the ground with the US fighters and bombers circling above to pinpoint ISIS targets. Combined with a more intensive series of air strikes on ISIS positions in and around Raqqa, the introduction of special forces is designed to improve the fighting capability of local Syrians forces who have an incentive in driving the terrorist group from their areas.

The plan sounds reasonable. Without local partners on the ground, the ability to push ISIS from the territory it currently controls and keep the group from returning will be virtually impossible. Without ground forces, any territory cleared from the air will simply have short-term effects. Yet with his latest decision, President Obama faces significant criticism from members of his own party.

Senators Tim Kaine, Martin Heinrich, Angus King, Brian Schatz, Chris Coons, and Chris Murphy all released statements on the same day as the President’s announcement, expressing their hesitancy or outright opposition to the latest deployment of US special operators. The common denominator that links these senators together is not their opposition to Obama’s strategy per se, but that the White House remains engaged in a war that Congress has not yet authorized through a formal Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF). Indeed, after nearly 8,000 airstrikes, the deployment 3,300 US personnel, and the spending of $5 billion over the past fifteen months of conflict, Obama continues to rely on a war resolution that was passed fourteen years ago against the al-Qaeda terrorist network, the organization responsible for the September 11 attacks.

With the exception of a draft ISIS-specific AUMF that passed through the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in December 2014, Congress has largely avoided the issue of war powers. The AUMF proposal that the administration submitted to Congress last February has been on the shelf without any action from the two committees responsible for overseeing the war resolution process: the House and Senate Foreign Relations Committees. The paralysis stems from opposing points of view drawn along party lines: Republicans consider the administration’s draft AUMF far too restrictive on the president’s ability to prosecute the war, while many Democrats view the resolution as not restrictive enough.

President Obama has found it exceedingly difficult to thread the needle between hawkish Republicans and dovish Democrats. With the exception of the 2001 AUMF that authorized the use of force against al-Qaeda, rarely has a president been fortunate enough to receive all of the war authority he has asked for. More often, Congress places time constraints, mission limitations, an extensive system of oversight, and certain conditions that that the administration must meet before the president could order the armed forces into action.

History is replete with case studies. The 1983 resolution that authorized US participation in the Lebanese peacekeeping mission required the White House to renew its mandate with Congress after eighteen months. The 1991 AUMF pertaining to Operation Desert Storm only allowed the use of the US military to enforce the list of UN Security Council resolutions that pertained to Saddam Hussein’s occupation of Kuwait. The 2013 AUMF that was debated in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which would have allowed the administration to use force against Syria’s chemical weapons facilities, prohibited the use of US troops on the ground for combat operations under any circumstances. Even the 2011 resolution that sought to provide domestic statutory authority for the NATO operation against Muammar al-Qaddafi expired after a full year—a sunset date that would either compel the president to end the mission entirely or return to Congress for an extension.

Republican lawmakers understandably worry that a new, ISIS-specific authorization would limit the ability of the US military to accomplish its mission. But history suggests that congressionally mandated limitations are quite normal. Of the seven war resolutions that a congressional committee or at least one house of Congress has voted on, five out of seven contained strict guidelines for the president.

How does this history apply to the ongoing war against ISIS in Iraq and Syria? If precedent over the past thirty-two years serves as a guide, any attempt by Congress to grant formal, statutory authority to the anti-ISIS campaign will likely constrain the president’s freedom of action. With the exception of the September 2001 resolution against al-Qaeda, rarely in recent history has Congress formally granted the president the power to deploy the US military in a long-term campaign as he sees fit. Therefore, any ISIL-focused resolution will contain time and/or geographical controls that would make it difficult for the US military to conduct offensive operations at full capacity. An authorization that allows the US military to operate only within the confines of Syria and Iraq, for instance, would prevent the use of force against ISIS affiliates in Libya or Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. If President Obama wanted to take action against the ISIS presence in Libya or Egypt, he would need to make the case that the group presents an extraordinary and direct threat to the security of the United States under his Article II constitutional powers. Article II, however, is not as sustainable and durable as congressional authorization in a fight that the administration’s own military advisers argue could last generations.

On the other hand, were Congress to pass a fresh AUMF on a bipartisan basis, the mission would enjoy the kind of domestic political support that puts all of America’s elected officials on the record. Every lawmaker, regardless of party or ideology, would be held accountable, a development that sends a strong and important message to the American people that their representatives take the issue as seriously as the men and women in uniform who conduct bombing runs and train Iraqi and Syrian fighters. A war authorization requested by the president and approved by Congress is by its nature beneficial for the intangible things: assuring the US pilots in the air and the US trainers on the ground that the entire US government supports the ultimate objective.

With the first deployment of US personnel in Syria, President Obama has once again opened up the debate that Congress has refused to have: whether to openly debate the US strategy on its merits and vote to approve or disapprove the use of military force. The question now is whether there is enough political will in Congress to authorize a military campaign that has already been going on for over a year—and whether Congress sees the pros of a new AUMF as outweighing the cons.

Daniel R. DePetris is a Middle East analyst at Wikistrat, Inc. and a contributor to The National Interest.

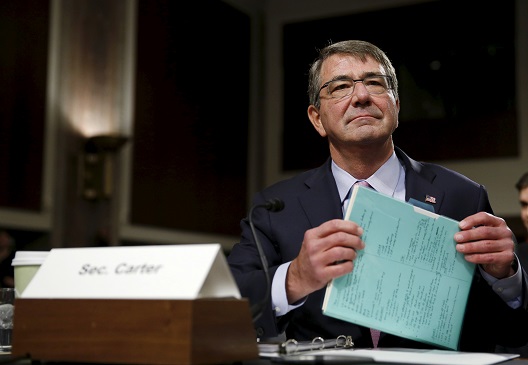

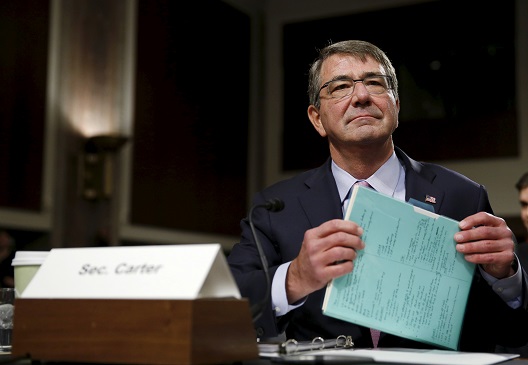

Image: United States Secretary of Defense Ash Carter prepares to testify at a Senate Armed Forces Committee hearing on "United States Strategy in the Middle East" in Washington October 27, 2015. (Reuters)