On July 6, the long-awaited British inquiry into the decision to invade Iraq in 2003 was released. In a 12 volume report that took seven years to complete, the public is given greater insight into then Prime Minister Tony Blair’s decision-making process, his relationship with then US President George W. Bush, and into the failure of the British government to consider the post-war impact on Iraq, and its role in rebuilding the country.

On July 6, the long-awaited British inquiry into the decision to invade Iraq in 2003 was released. In a 12 volume report that took seven years to complete, the public is given greater insight into then Prime Minister Tony Blair’s decision-making process, his relationship with then US President George W. Bush, and into the failure of the British government to consider the post-war impact on Iraq, and its role in rebuilding the country.

Speaking to MENASource, Dr. Nussaibah Younis, the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East Senior Fellow on Iraq, delves into what the Chilcot Report means for the British government, the families of the British soldiers who died in Iraq, and the Iraqis themselves, reeling from a devastating bombing that has left over 250 people dead in Baghdad.

Q: What does the Chilcot Report say, and does it lay to rest the question of the legality of the British involvement in the 2003 invasion of Iraq?

Nussaibah Younis: The Chilcot report doesn’t address whether or not the Iraq war was legal. What it does state is that the preparation running up to the Iraq War was woefully inadequate, and that the political establishment, the intelligence community, and the military forces in the United Kingdom should have done a better job in interrogating the government over the assumptions it had made to justify invading Iraq and over the state of the war plans, and in particular, should have interrogated the government more closely over its decision to leave the war planning entirely up to the Americans.

Q: So what criticisms does the report make?

NY: There was a sense in the British government that the post-war plan was going to come from the Americans, and that British would slot in wherever the Americans needed assistance. But that planning wasn’t being done at all. There was too much positivity and not enough critical engagement on behalf of the entire political establishment and the supporting civil service establishment and that’s really where the biggest criticism comes from in the Chilcot report.

Other key criticisms have included the way in which Prime Minister Tony Blair presented the assessments he had gained from the intelligence community. He had gained assessments that were not entirely coherent, and certainly not ironclad, and was then turning around, not only in public, but also to his cabinet and to parliament, and presenting that same evidence as if it were far stronger and far more compelling than the intelligence he actually received.

Chilcot stopped short of saying Tony Blair intentionally misled the British public, or for that matter the British parliament, but there’s certainly a suggestion that facts were somewhat massaged or presented differently because Tony Blair was pre-committed to bring the United Kingdom into this war, and that facts and the intelligence assessment weren’t necessarily driving him at the time.

Q: In reports on the inquiry today, there has been a sense that Blair’s decisions were influenced by an interest to protect UK-US relationship. How does the report, in reality, handle that question? Is it explicit in how it addresses that relationship?

NY: No – it’s implied. A lot of the report is couched in much more sensitive language. It suggests that these are some of Tony Blair’s preoccupations but doesn’t outright accuse him of lying or manipulating. There’s long been criticism in the United Kingdom over what was seen as an inappropriately close relationship and there’s been a lot of concern and skepticism over the shared ideology—this kind of neo-liberal interventionism—that Bush and Blair were seen to share. In the memos that have been published in this report—and are the reason it was delayed for so many years, because of the sensitivities of releasing these private exchanges—the exchanges make clear that Tony Blair was committed by whatever means to supporting the United States in its intervention in Iraq, totally apart from whatever evidence there may or may not have been around the question of WMDs.

The perception that’s long been held in the United Kingdom and, an accusation that has long been leveled at that Labor government, that WMDs were used as an excuse and that intelligence was trumped up to make the case for war—I think all of those accusations have been very well substantiated by this report.

Q: How does the report handle the UK’s actual performance in Iraq?

The report is critical of the performance of the United Kingdom—that there was a huge gap between the ambitions of this kind of nation building project and the resources that both the UK and US were prepared to put forward. Its performance, particularly in Basra where it took a lead, was woefully inadequate. They ended up making humiliating deals with local militias just to stop their troops from being fired on, they made very little in the way of lasting impact, developed very little infrastructure, and Basra is now a pitiful place despite the vast oil wealth that springs forth from its own land. At the end of the day, in 2009, the Brits packed up and left with their tail between their legs having accomplished virtually nothing. From start to finish, it’s a pretty devastating report.

Q: How does the report address the question of the UK’s role in the post-war planning in Iraq?

NY: It just talks about the fact that the UK didn’t see post-war planning as its responsibility or its role. And from the US perspective—they were planning for the post-war situation in terms of a humanitarian crisis. The US was expecting refugees, thinking about camps, about movement of food, and it wasn’t seen beyond the actual overthrow of Saddam, it wasn’t seen as a security mission or as a nation building mission, but more as a simple post-war dealing with refugees, and rebuilding infrastructure, and then handing over to the Iraqis. There was just very little sense of what kind of internal conflicts might be triggered by the removal of Saddam Hussein and nothing like the level of security or the number of troops to prevent the looting that we saw very early on and to impose law and order and to ensure security of people who were hunted down for one vendetta or another – there was a real under-emphasis on security in the post-war planning.

Q:With the publication of the report, families of the British soldiers who were killed in Iraq, are reiterating their call for Blair to be brought up on war crime charges. Can this report have any impact on that issue?

NY: I think that this report is going to be seen as inadequate for those families that feel that the war was fought under false pretenses, and who want to see Tony Blair held to account. The report doesn’t take a stand on legality, it doesn’t outright accuse Blair of intentionally lying or intentionally misleading the British public or parliament, and it doesn’t really lay the groundwork for any further action to be taken against him. Also there just aren’t statutes or precedents in particular in either British law or in the International Criminal Court that lay the basis for any further proceedings against Tony Blair, and we were well aware of this, so I think that the families of the soldiers, unfortunately, are likely to continue to feel that justice has not been served.

Q: What is the impact of this report on Iraqis? The Iraqi Foreign Minister, when asked to comment on the report, responded ‘What report?’ Does this represent the general Iraqi response to the Chilcot Report?

NY: In Iraq, several days ago, over 250 civilians were killed in a shopping district in Baghdad called Karada. It was a devastating bombing – the single largest bombing in Iraq since 2003 – at a time when we had the victory against Fallujah, and Iraqis, particularly Baghdadis, had been hoping for some respite from the car bombings. And yet this bomb managed to make its way into Baghdad from Diyala past who knows how many checkpoints and how many corrupt police officers. Diyala is dominated by Iraqi militias, and has always been a source of instability and violence, and is somewhere that Iraqi security forces have always been aware of being a source of potential bombings. For a vehicle of that size to make it to this area without being checked is an indictment of the Iraqi political establishment and the security services. And that’s why we’ve seen people take to the street absolutely furious at the Prime Minister, and that’s why we’ve seen the resignation of the Interior Minister. So Iraqis are preoccupied with the failure of their own government today, and with the challenges that continue to be posed by ISIS, by the economic crisis the country is facing, by the needs of internally displaced people, by the need to reestablish some sort of security in Baghdad from these car bombings. So I think to Iraqis, the Chilcot Report seems like a naval gazing, academic exercise, that’s almost offensive in its irrelevance to what Iraqis are going through today, and to the kind of support they need today.

Q: We often hear that the invasion of Iraq gave rise to groups like ISIS. Does the report lend any sort of context or understanding that the recent bombing in Baghdad was a direct result of the war in Iraq?

NY: The report acknowledges, and Chilcot certainly acknowledged in his press conference today, that the repercussions of the invasion of Iraq are still very much with us, and that the evolution of ISIS has come out of the invasion of Iraq. But I think it’s important to note that the fundamental damage that was done to Iraqi society, was done in large part by Saddam Hussein and by the Baathist party. When you look at some of the tactics that ISIS uses and their radicalization—much of that has its roots in Baathist Iraq, in the kind of tactics that Saddam Hussein used. Many ISIS members have their military training from Saddam’s Iraq and their experience as intelligence operatives in one of the most horrific intelligence structures that we’ve ever seen in the world—a lot of the roots of the violence and the anger and particularly the sectarian and ethnic anger and divisions—those seeds were sown by Saddam Hussein and we see a similar thing in Syria. ISIS is a product, in many ways, of authoritarianism, and what authoritarianism does to societies. So I think even if there hadn’t been an invasion, eventually we would have seen an attempt to overthrow Saddam Hussein’s regime, which would have been extremely bloody and violent and could well have led to the emergence of something similar to ISIS.

Q: What impact could the report have on the region as a whole?

NY: What’s most damaging about a report like this, though of course it’s not its intention, it can end up being used to make the argument against the intervention of the international community into areas where there is great humanitarian tragedy taking place, and I think the tragedy of the Iraq war has been in part the reaction to the crisis in Syria, and by the international community’s unwillingness to intervene in Syria by learning all the wrong lessons from the Iraq war, which is not that you don’t ever intervene, but that when authoritarian regimes come apart, there’s a lot of violence and ugliness, and it takes time for those societies to heal but that protecting civilian populations in the wake of those kinds of disintegrations is absolutely necessary, is in our national security interest, and is the responsibility of the international community.

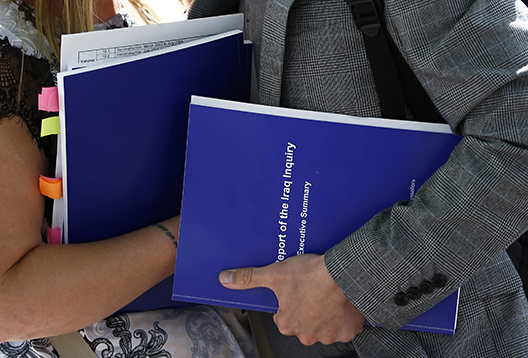

Image: A relative of a British soldier killed in Iraq, holds a copy of The Report of the Iraq Inquiry, by John Chilcot, at the Queen Elizabeth II centre in London, Britain July 6, 2016. (Peter Nicholls/Reuters)