The Egyptian president, Mohamed Morsi, has already answered the question in the title by declaring that “Egypt will never go bankrupt”. But judging by some of the recent headlines, skeptics are still unconvinced. What does it mean for a country to go bankrupt anyway? And is Egypt really on the brink of financial collapse?

Rather than using the poorly-defined term “bankruptcy”, an alternative way for analyzing the financial sustainability of a country is to assess its ability to meet its external financing needs, which consist of:

- Trade deficit (excess imports over exports)

- Interest payment on existing debt

- Paying back external debts as they fall due

In the short term, external financing needs can be met by borrowing or drawing from foreign currency reserves. But no country can borrow forever and reserves will eventually be exhausted, so the economy must eventually adjust to rebalance external finances.

In an ideal world, the adjustment is done in a benign manner in which the country gradually winds down its debt, boosts exports and reduces imports costs. But in times of crisis, a country may be forced to do the whole adjustment momentarily by defaulting on debt and instantaneously cutting imports—including food, medicines and energy needs. This is the dreaded “going bankrupt” scenario. One reason for the unpopularity of the IMF standard conditions is that the speed of adjustment they require is too quick for most countries’ liking.

So what are the external financing needs for Egypt over the next few months? And does it have sufficient funds to avoid hard-landing?

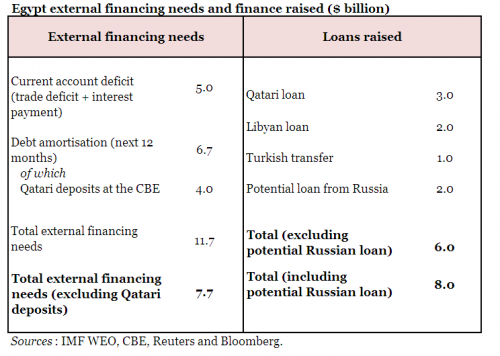

The IMF currently estimates Egypt’s external financing needs to be $11.7 billion. This figure can be split into $5 billion of expected current account deficit (that is trade deficit plus interest payment), and $6.7 billion of maturing external debt over the next 12 months. Raising $11.7 billion over 12 months may seem formidable, especially without the help of the central bank’s foreign currency reserves which are near their minimum safety level. But a more careful look at the numbers suggests it is not so bad.

According to the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE), of the $6.7 billion of external debt maturing this year, $4 billion are Qatari deposits which are unlikely to be paid back anytime soon. On top of that, Egypt has recently managed to borrow $2 billion from Libya and an additional $3 billion from Qatar. With a further $1 billion transfer from Turkey and a potential loan from Russia, the Egyptian government seems to have secured most of its external financing needs for the next few months as the table below shows.

Despite its success in securing loans, the government’s strategy carries some risks. First, it could unravel if the financing needs increased unexpectedly as a result of energy or food price shock. A second risk is that of a speculative attack on the Egyptian pound, especially with the CBE unwilling and unable to fend them off. Third, the over-reliance on Qatari funds to keep the Egyptian economy on its feet may raise questions about the political price being paid. Fourth, even if this tactic proves successful, it is at best a short-term fix rather than a long-term solution.

But the Egyptian government seems willing to take these risks rather than embarking on the unpopular and painful economic measures requested by the IMF. Perhaps it is hoping to kick the can just far enough down the road beyond parliamentary elections.

Ziad Daoud is an economist currently working for an asset management firm. He completed his PhD at the London School of Economics.

This article was originally published on Awraq.

Photo: Nasser Nouri

Image: Bakery%20Nasser%20Nouri.jpg