From Charlemagne, the Economist: Hardly a meeting of foreign ministers passes without punitive measures against a brutal regime: import and investment bans, restrictions on financial dealings, hit-lists with hundreds of people stopped from entering the EU and having their assets frozen. “We have become a sanctions machine,” quips one minister.

In January the EU imposed a fifth round of sanctions on Iran. This included banning oil imports and freezing the assets of the Iranian central bank. This month it turned the screws on Syria again. Here, too, the EU acted against the central bank, and seven Syrian ministers were put on the list. In Belarus 21 new people were similarly “designated”, mostly policemen and judges involved in suppressing civil rights. In the ensuing tit-for-tat, Belarus demanded the withdrawal of the Polish and EU ambassadors in Minsk, and EU members recalled their envoys for consultations. Since 2010 the EU has imposed sanctions against Myanmar, Zimbabwe, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya (some have since been relaxed, as regimes fall or change behaviour).

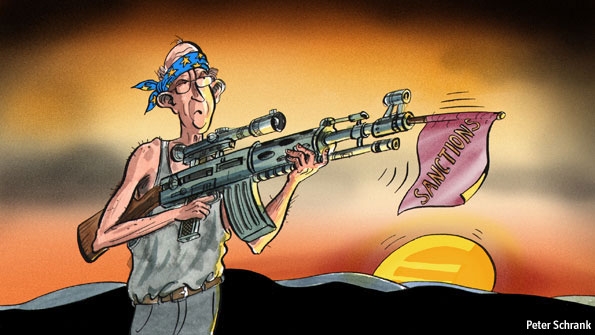

This machinegun fire of sanctions is due, in part, to circumstance. The suppression of uprisings across the Arab world demanded an urgent response. The EU now has a permanent diplomatic arm, the European External Action Service (EEAS), that is good at sanctions. Securing agreement for them among 27 members is an achievement. Even the usually despairing Americans are impressed.

Still, sanctions are uncertain. Twelve years of tough ones against Iraq did not dislodge Saddam Hussein (that took an invasion). Sanctions may have contributed to the downfall of Laurent Gbagbo in Côte d’Ivoire and Muammar Qaddafi in Libya, but the decisive blows were military. In Iran escalating sanctions have not dissuaded the regime from its nuclear ambitions, though they may push it into more talks with the EU’s diplomatic chief, Cathy Ashton. That said, the sanctions were aimed as much at convincing Israel that it did not yet need to bomb Iran.

In Syria sanctions seem so far to be doing little to stop Bashar Assad from bleeding his country. The international response is hampered by Russia and China, which have vetoed a UN resolution, fearing it would invite a Libyan-style intervention. This week’s EU summit was discussing how to prise Moscow and Beijing apart. But even if the UN could act, Britain and France might not be keen on military action. Syria is a stronger foe than Libya, and the consequences of intervention are less predictable.

The sanctions policy may soon reach its limits in terms both of people and transactions to ban and of interests among European states. Slovenia has vetoed placing a Belarusian oligarch on the sanctions list, apparently to protect a firm with a juicy contract to build a housing and office complex in Minsk, complete with a new Kempinski hotel. To impose oil sanctions against Iran took a promise to help debt-crippled Greece find an alternative source of oil (and soft finance). The Greeks blocked moves to ban imports of phosphates from Syria. (graphic: Peter Schrank/Economist)

Image: economist%203%201%2012%20EU%20sanctions.jpg