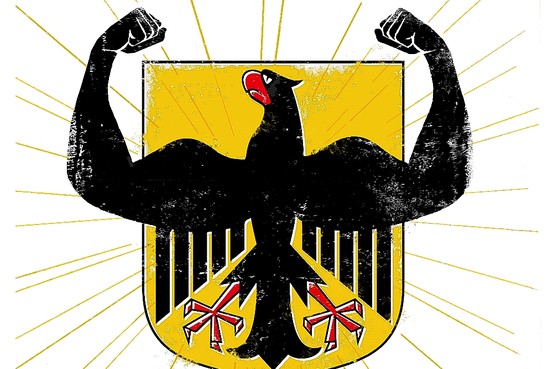

From Marcus Walker, the Wall Street Journal: What is Germany’s place in the world?

German leaders argue that they don’t want to tinker with a winning formula, and they’re already making significant contributions to the EU and NATO. But critics see it differently. They attack the country for wanting to be a big Switzerland: a trading nation that profits from the business opportunities of a globalized economy but shirks the dirty work of globalization, including international involvement in armed conflicts.

Germany’s traditional allies even fret that the country is losing interest in Europe and the West. . . .

Both NATO and the EU were built around Germany, by allies that wanted to bind Europe’s strongest country into a multilateral structure. Germany, rueful of its history, also felt more comfortable inside their embrace.

Today’s Germany, more confident of its own strength and virtue, exudes the sense that it no longer needs either alliance quite as much as it used to. Only 24% of Germans see more upsides than downsides to EU membership, while 31% see more downsides and 40% say it’s a mixed bag, according to a survey published in German newspaper Die Zeit in March. . . .

Euro-rhetoric is no longer effective, "because peace in Europe is no longer in question," says Volker Perthes, director of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. "You need to explain to people, more than in the past, why burdens for German taxpayers are in their interests. . . .

NATO allies are worried by the revival of a pacifist stance under German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle.

German pacifism after World War II was long tolerated, even welcomed, in a Europe that had suffered from German militarism. But since the 1990s, Germany was supposed to become a "normal" country again, one that took part in multilateral interventions in war-torn places such as Kosovo and Afghanistan.

When the UN Security Council voted for military intervention in Libya, Germany abstained, breaking with its NATO allies. Germany even withdrew its ships from NATO naval patrols in the Mediterranean, since such patrols were now enforcing a UN-mandated arms embargo against Col. Moammar Gadhafi.

In a speech to Germany’s parliament, Mr. Westerwelle denied the country was isolated, because it had voted the same way as "important countries and partners such as Brazil, India, Russia and China."

The implication was that in Germany’s new foreign-policy doctrine, the BRICs—Germany’s booming new export markets—are interchangeable with the West as Germany’s partners, depending on the circumstances.

Many German lawmakers are uncomfortable with Mr. Westerwelle’s policy, and Ms. Merkel has made efforts to repair relations within NATO. But opinion polls showed ordinary Germans want just as little to do with the Libya conflict as their foreign minister.

"Some Germans have become pacifistic and have forgotten about responsibility," says [former German economy minister Michael] Glos, the conservative lawmaker. "Pacifism is cheap when others manage conflicts."

Plenty of other European countries are also inward-looking, says Ulrike Guerot, senior fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations in Berlin. "But we Germans have to learn that we matter more than others in Europe," she says.

Mr. Walker is a staff reporter of The Wall Street Journal in Berlin. He can be reached at marcus.walker@wsj.com. (graphic: Edel Rodriguez/Wall Street Journal)

Image: wsj%206%2028%2011%20Germany.jpg