From the European Institute: So what does Libya show about Western military cooperation in trying to control future conflicts even against minor rogue states? It shows that NATO without the U.S. cannot handle an expeditionary war even on the scale of Libya , which is conveniently located just across the Mediterranean from NATO airbases in Libya, enabling European fighter-bombers to reach their targets without having too rely too heavily on aircraft carriers. (This campaign had only a French and an Italian carrier.) Europe also faces shortages in precision-guided missiles that would make it hard to sustain a similar operation for a similar length of time. On the U.S. side, Barack Obama’s decision to “lead from behind” amounts to a warning about restrictions on readiness in Washington to take on military action in situations that do not involve American interests directly. With the Pentagon facing cuts (perhaps deep ones) in its budget, the words of former Defense Secretary Robert Gates have more meaning than the old refrain about the Europeans needing to do more to shoulder their fair share of the burden of collective defense. In a farewell speech earlier this year, Gates said that the U.S. has a “dwindling appetite” to serve as the heavyweight partner in the military order that has underpinned the transatlantic relationship since World War II and condemned planned European defense cuts, saying that Americans are tired of engaging in combat missions for those who “don’t want to share the risks and the costs.” U.S. officials have subsequently insisted that Gates was not announcing the demise of NATO but merely seeking to goad the Europeans into “smarter” use of their defense resources and better “pooling and sharing’ in their military planning.

Even when slightly recalibrated by U.S. officials to be a positive call to arms, Gates’ stinging speech rings as a real warning that the U.S. may no longer be prepared to take military action mainly to “save the alliance” from crises that centrally involve Europe and not the U.S. — as it did in 1999 in Kosovo and now again in Libya.

Taken together, the situations on both sides of the Atlantic after this strange North African campaign seem to indicate that the longstanding terms of the old military relationship within the West between America and Europe have ended, buried in the Libyan sands. At the same time, the new pragmatism that prevails in Paris – and in Washington and London – seems to leave open as many doors as leaders can imagine. Whether or not anyone uses these openings, of course, is another question.

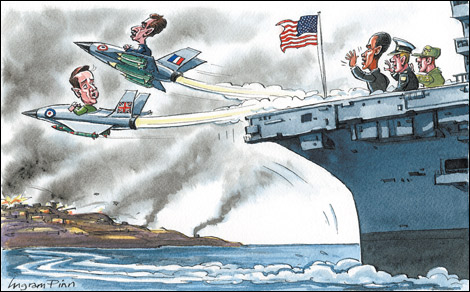

Alain Frachon, Senior Editor at Le Monde newspaper. (graphic: Ingram Pinn/Financial Times)

Image: ft%203%2025%2011%20%20Ingram%20Pinn.jpg