From Anders Fogh Rasmussen, NATO: [D]efence spending among the Allies is increasingly uneven, not just between North America and Europe, but also among European Allies. Moreover, total defence spending by the Allies in recent years has been going down, while the defence spending of new and emerging powers has been going up. If these spending trends continue, we could find ourselves facing three serious gaps that would place NATO’s military capacity and political credibility at risk in the years to come.

There is a risk, first of all, of a widening intra-European gap. While some European Allies will continue to acquire modern and deployable defence capabilities, others might find it increasingly difficult to do so. This would limit the ability of European Allies to work together effectively in international crisis management.

Second, we could also face a growing transatlantic gap. If current defence spending trends were to continue, that would limit the practical ability of NATO’s European nations to work together with their North American Allies. But it would also risk weakening the political support for our Alliance in the United States.

Finally, the rise of emerging powers could create a growing gap between their capacity to act and exert influence on the international stage and our ability to do so.

Of course, investment in defence cannot solve our economic problems. But if we cut defence spending too much, for too long, there is the risk that we could actually make the economic situation worse. Disproportionate defence cuts not only weaken our military forces, but also the industries that support them and which are important drivers for innovation, jobs and exports. This would lead to a dangerous downward spiral of lower growth and smaller and less effective militaries, particularly in Europe.

Governments need to focus on fighting the economic crisis and defence spending cannot be immune as they try to balance their budgets. However, the security challenges of the 21st century – terrorism, proliferation, piracy, cyber warfare, unstable states – will not go away as we focus on fixing our economies. While it is true that there is a price to pay for security, the cost of insecurity can be much higher. Any decisions we take today to cut our defence spending will have an impact on the security of our children and grandchildren.

Hard power will remain essential if we want to keep our populations safe and retain our global influence. This is why NATO Allies must hold the line on defence spending in 2013. We must also do more to get the most out of the funds and resources that we do have; multinational solutions will be vital for minimising our costs and our Alliance will be vital for maximising our capabilities. Then, as soon as our economies improve, we should consider increasing our investment in defence so that we can close the gaps. . . .

[T]he effects of the financial crisis and the declining share of resources devoted to defence in many Allied countries have resulted in an over-reliance on a few countries, especially the United States, growing capability disparities among European Allies, and some significant deficiencies in key capabilities, such as intelligence and reconnaissance, as illustrated by NATO’s experience in Libya. In 2012, with the approval of the Defence Package and key initiatives such as Smart Defence and Connected Forces, Allies have started to take steps toward addressing these issues.

The combined wealth of the non-US Allies, measured in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), exceeds that of the United States. However, non-US Allies together spend less than half of what the United States spends on defence, and in the decade since 2001 – the year of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States – their annual increases in defence spending have been significantly less. Since 2008, defence spending by most non-US Allies has declined steadily. . . .

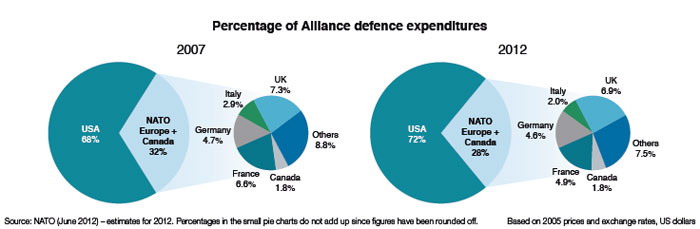

The pie charts show that the United States’ share of Alliance defence spending2 has increased from 2007 to 2012. While France, Germany and the United Kingdom together represent more than 50 per cent of the non- US Allies defence spending, more recently their defence spending has come under increasing pressure. The share of the other European Allies together has fallen from 8.8 to 7.5 per cent.

In 2006, Allies agreed to commit a minimum of two per cent, as a percentage of GDP, to spending on defence. The graph below shows how Allies are performing against this NATO two per cent guideline. In 2007, only five Allies spent more than two per cent; in 2012 this number had declined to four. . . .

The result of these disparities in investment is two-fold: an ever greater military reliance on the United States, and growing asymmetries in capability among European Allies. This has the potential to undermine Alliance solidarity and puts at risk the ability of the European Allies to act without the involvement of the United States. Cuts in European equipment procurement could also weaken Europe’s defence industrial base and the ability of European armed forces to remain at the cutting edge of technology.

Excerpts from "Secretary General’s Annual Report 2012," by Anders Fogh Rasmussen. (graphic: NATO)

Image: nato%201%2031%2013%20SG%20report%2020130129_sg_report-2012-08.jpg