From Kenneth M. Pollack, the Washington Post: If Washington does choose to intervene, however, there are ways to reduce these risks. First, America could start providing lethal assistance, particularly more advanced anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons to help kill off the regime’s heavy weapons faster and allow the opposition to prevail more quickly.

Even more important, the United States and its NATO allies could begin to provide military training for Syrian fighters. More competent opposition forces could better meet and defeat government troops. Such training would also help diminish the factionalism among the armed groups and bring greater discipline to the opposition, including in a postwar environment. Indeed, the American program to organize and train a Croatian (and Bosnian Muslim) army in the mid-1990s was crucial both to military victory in the Bosnian civil war and to fostering stability after the fighting.

Moreover, one of the best ways for the United States to influence a post-civil-war political process is to maximize its role in building the military that wins the war.

Ending a war vs. building a nation

Historically, the only real alternative to ending a civil war by picking a winner is for an outside force to suppress the warring groups and then build a stable political process that keeps the war from resuming. The military piece of this — shutting down the fighting — is relatively easy, as long as the intervening nation is willing to bring enough force and use the right tactics. The hard part is having the patience to build a new, functional political system. The Syrians in Lebanon, NATO in Bosnia, the Australians in East Timor and the Americans in Iraq demonstrate the possibilities and the pitfalls.

This course is typically the only way to end the violence without the mass slaughter of the losing side. It also can prevent fragmentation and an outbreak of fighting among the victors. If done right, it can even pave the way toward real democracy (as the United States started to do in Iraq before its withdrawal last year), which results in greater stability in the long run.

But it is not cheap, and it requires a long-term commitment of military force and political and economic assistance. The cost can be mitigated in a multilateral intervention such as in Bosnia and Kosovo, rather than a largely unilateral effort along the lines of the U.S. reconstructions of Iraq and Afghanistan. In the case of Syria, that means the United States isn’t the only nation that needs to sign on; Turkish, European and Arab support matter as well.

Right now, there is absolutely no appetite in the United States for a Bosnia-style intervention in Syria. That is understandable. Unlike in Libya, the humanitarian disasters unfolding in Syria have not been enough to galvanize the United States to action. In addition, there is nothing intrinsically important there for U.S. vital interests. Syria does not have significant oil reserves, nor is it a major trading partner. It is not an ally and was never a democracy. If Syria were merely to self-immolate, it would be a tragedy for the Syrian people but extraneous to American interests.

However, if Syria’s civil war spills over into the rest of the Middle East, U.S. interests would be threatened. Civil wars often spread — through the flow of refugees, the spread of terrorism, the radicalization of neighboring populations, and the intervention and opportunism of neighboring powers — and Syria has all the hallmarks of a particularly bad case.

At its worst, spillover from a civil war in one country can cause a civil war in another or can metastasize into a regional war. Sectarian violence is already spreading from Syria; Iraq, Lebanon and Jordan are all fragile states susceptible to civil war, even without the risk of contagion. Turkey and Iran are mucking around in Syria, supporting different sides and demanding that others stop doing the same. Terrorism or increasing Iranian influence might pull even a reluctant Israel into the fray — just as terrorism and increasing Syrian dominance pulled Israel into the Lebanese civil war years ago.

This is what we must watch for. Spillover may force Washington to contemplate real solutions to the Syrian conflict, rather than indulge in frivolous sideshows. If that day comes, our choice will almost certainly be between picking a winner and leading a multilateral intervention.

Chances are we will start with the former, and if that fails to produce results, we will shift to the latter. That may seem far-fetched, but it is worth remembering that in 1991 there was virtually no one in the United States who supported an American-led multilateral intervention in Bosnia, and by 1995 the United States, under a Democratic administration, was doing just that.

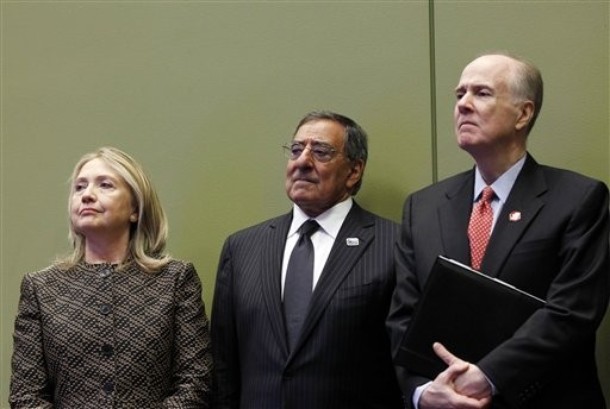

Kenneth M. Pollack is a senior fellow at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. He is the author of “A Path Out of the Desert: A Grand Strategy for America in the Middle East.” (photo: AP)

Image: ap%208%2012%2012%20Clinton%20Panetta%20Donilon.jpg