The Pentagon is suggesting the world’s chemical weapons watchdog use a U.S.-made mobile destruction unit in Syria to neutralize the country’s toxic stockpile, officials told Reuters.

The Pentagon is suggesting the world’s chemical weapons watchdog use a U.S.-made mobile destruction unit in Syria to neutralize the country’s toxic stockpile, officials told Reuters.

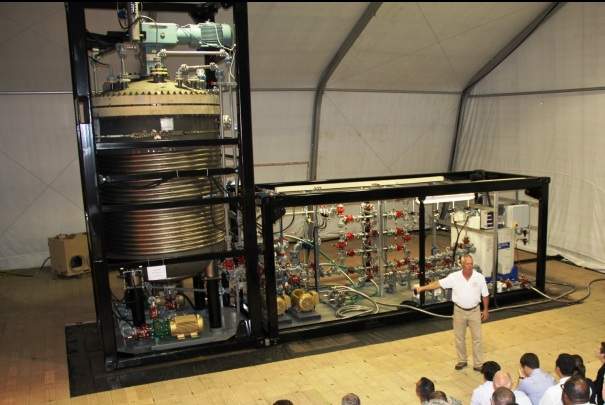

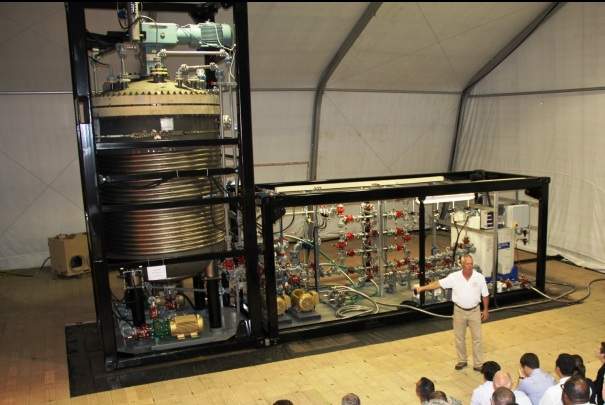

It gave a briefing on the unit on Tuesday to officials at the Hague-based Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, who are deciding what technology to use for the ambitious chemical weapons destruction plan, two officials said. . . .

“Our people’s initial response was that it looks encouraging. It looks ideal,” said a source in the OPCW who attended the briefing. “But we don’t know how it will perform in the field and we would like to know the response from Syria and other countries with similar technology.”

The source said two of the units have been produced and several more are under production.

It will largely depend on how Syria’s suspected 1,000 tons of sarin, mustard and XV nerve agents are stored. The unit can destroy bulk chemicals, or precursors, but not munitions with a toxic payload. Separating these is more dangerous and time-consuming than incinerating or neutralizing precursor chemicals. . . .

Several countries have already been contacted to provide technicians for trials with the U.S.-made unit, which finished a trial stage in August after half a year of development, said a source who asked not to be named. It is known as the Field Deployable Hydrolysis System (FDHS).

A U.S. defense official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the unit costs roughly $5 million to build. . . .

Experts say meeting the June 2014 deadline for complete destruction is a difficult goal because the chemicals and weapons are spread over dozens of sites and foreign inspectors have never worked in an ongoing conflict.

Ceasefires will have to be negotiated with opposition forces to allow for safe access to sites in their territory in a conflict that has already claimed 100,000 lives.

The U.S. unit, built by the ECBC and the government’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency, is operated by a crew of 15. It can destroy up to 25 metric tons of chemical agents per day when run around the clock, according to Edgewood.

Image: Demonstration of the Field Deployable Hydrolysis System (photo: US Army)