Secretary of Defense Robert Gates on June 10th painted a very grim picture of NATO’s possible future – and thus the future U.S. role in Europe and prospects for U.S.-European cooperation. Less than a week earlier, the same Secretary Gates had outlined a bullish future for the U.S. in the Asia-Pacific region – a U.S. determined not only to maintain its military presence but to increase its forces and strategic commitment.

The NATO Gates warned in Brussels that U.S. fiscal problems and the failure of most European NATO members to share the burden foreshadowed the “real possibility for a dim, if not dismal future for the transatlantic alliance.”

The Asia Pacific Gates, on the other hand, explained that U.S. debt and budget problems would not prevent the United States from maintaining a strong regional presence and keeping its commitments in Asia. Speaking at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, he asserted that “ irrespective of the tough times the U.S. faces today, or the tough budget choices we confront in the years to come,” U.S. interests as a Pacific nation will endure and “the United States and Asia will only become more inextricably linked over the course of this Century,” which argues “strongly for sustaining our commitments to allies while maintaining a robust military engagement and deterrence posture across the Pacific Rim.” AP Gates outlined a series of steps planned to enhance the U.S. military posture in the region and asserted that “America is, as the expression goes, putting ‘our money where our mouth is’ with respect to this part of the world – and will continue to do so.”

Why the “two Gates”? This may reflect a number of factors. In transatlantic relations, Gates was seeking to send a jolt through NATO capitals in perhaps fast-fading hope of a “reset” in the NATO countries’ political and military commitments to the alliance. He reeled out depressing statistics of the huge disparities between the U.S. and the rest of the NATO countries and pointed to the unpreparedness to even fight a small war against Libya without the U.S. in the lead in capabilities and resources. He warned against Europe turning away from meeting its responsibilities even to its own immediate defense as well as from a larger sense of its “out of area” mission. While the U.S. is worried about NATO cohesion and commitment to share the defense burden, Washington does not need to play the role of an external balancer to provide reassurance to nations facing uncertainty about the role of an emerging great power in their region.

The contrast with the U.S. in Asia is striking. The Asia-Pacific Gates was clearly trying to reassure Asians that despite U.S. fiscal problems, the United States is determined to maintain and even enhance its role in the region. There was no badgering of allies and friends to do more but rather an effort to convince states worried about China’s rise that the U.S. would bear the burden, despite fighting two wars and looming further defense budget cuts, to preserve peace and stability in the region. The U.S. wants to enhance its bilateral alliances with regional states and hopes they will make greater commitments. But there is no regional multilateral alliance like NATO that is failing to live up to its commitments. The U.S. has long been the regional superpower and balancer – and regional states are eager that it continue to credibly play that role. Ironically, while China is the focus of U.S. and Asian states concern about potential imbalances and instability, the U.S. presence serves Beijing’s interests by reassuring regional states which otherwise might be more reluctant to strengthen interdependence and political ties with China.

Gates was sufficiently confident about the long-term staying power of the U.S. in Asia that he responded to a taunt from persistent Singaporean critic Kishore Mahbubani about the staying power of the United States by offering a $100 bet that “five years from now the United States’ influence in this region is as strong if not stronger than it is today.”

There is, of course, only one “Gates.” But the contrast in the Secretary’s speeches is indicative of the shift in power and wealth from West to East – and the determination of the United States to remain the major player in the East as well as the West despite the “rise of the rest.”

Banning Garrett is the Director of Asia Program and Strategic Foresight Project, Atlantic Council.

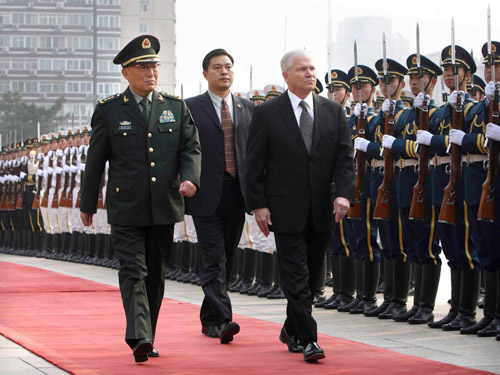

Image: gates_PLA.jpg