Beyond power machinations and political maneuvering, events in Saudi Arabia signal a more important, historic shift is underway

Riyadh – King Salman’s unprecedented purge of the Saudi royal family this week was an earthquake whose ongoing aftershocks will go far beyond the country’s borders—rippling out across the Islamic world from the custodian of Mecca.

The purge’s possible architect and certain benefactor was the king’s son, the 32-year-old Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who is engaged in one of the most audacious political and economic gambles of our times. Yet perhaps even more far-reaching have been his moves toward social liberalization and his public appeals for “moderate Islam.”

Talk to royal family members over the age of 50 and you’ll hear whispered trepidation over what they consider the reckless actions of a headstrong prince. By contrast, among Saudis under 30, who make up more than half the population, and women, who account for the majority of the country’s graduate students, one hears a new sense of optimism and opportunity.

The facts by now are well known, but their importance remains underestimated.

King Salman and his son, referred to by Western diplomats as MBS, moved with ruthless speed this past week to arrest more than 60 princes and business leaders on corruption charges, shutting down more than a thousand accounts, with the potential to confiscate more than $800 billion in assets.

The latest shock is the move to freeze the account of Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, the man MBS replaced as crown prince last June. And perhaps the most telling arrest was that of the powerful Miteb bin Abdullah, son of late King Abdullah and an earlier pretender to the throne, who controlled the National Guard—a palace guard force charged with protecting royals (or potentially supporting coups against them).

A Saudi official explained MBS’ head-spinning tempo, using a bike-riding metaphor. If the bicycle rolls too slowly, it could topple, tossing its rider. If the bike races too quickly, it risks the danger of a more violent, devastating crash. MBS, the official said, must have had reason to decide slow-going posed enough of an immediate danger that it was wiser to risk over-acceleration.

How MBS manages his ride from here will have regional and global consequences. That may sound hyperbolic given Saudi Arabia’s modest size, with a population around 30 million people. Yet the country’s outsized importance has other sources.

With Mecca and its two million annual pilgrims, Saudi Arabia is the center of global Islam. With its escalating battle with Iran, it is the vanguard in the Sunni-Shia rivalry. As one of the world’s top two oil producers and exporters, it remains a force in the global economy. And as the largest military power among the Arab Gulf states, it is a key US regional ally against terrorism.

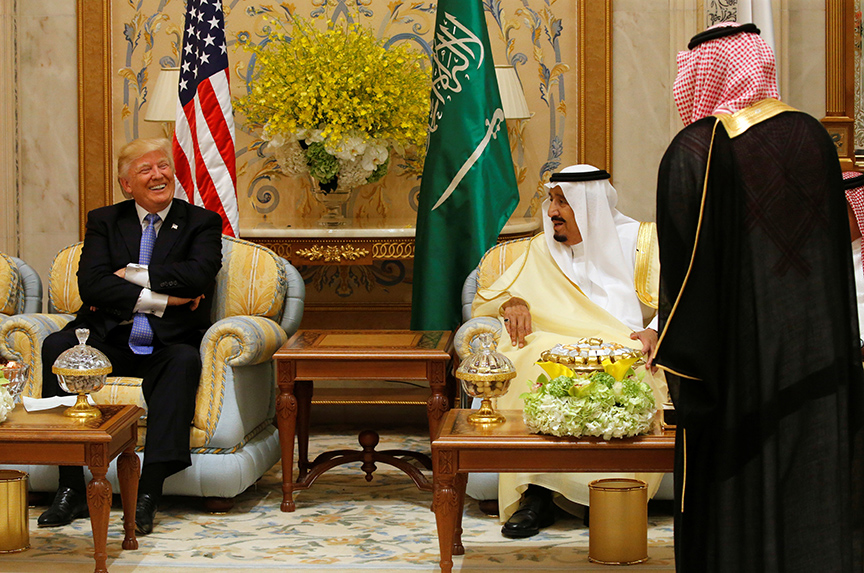

US President Donald J. Trump (left) waited for the start of an event with Saudi Arabia’s King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (second from right) and Gulf Cooperation Council leaders at their summit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on May 21. (Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

Most of the attention showered on the crown prince in past weeks has focused on his economic modernization plans, under the heading of Vision 2030. More recently, the world’s attention has been drawn to his moves toward social liberalization and statements on religion—reigning in religious police, providing women the right to drive cars (announced by royal decree in September), opening cinemas (later this year), and permitting women to vote in municipal elections.

Just a few days ahead of the purge, the crown prince convened some 3,000 global investors at his Future Investment Initiative. Some Western media focused on the gimmick of the Saudis presenting the first national citizenship to a robot named Sophia. More interest was showered on the crown prince’s rollout of a $500 billion investment project for the new city of Neom, in the Gulf of Aqaba, an economic zone that will have its own judicial system and tax and labor laws, and power itself through wind and solar energy.

While the Islamic world took clear notice, too little Western attention focused on MBS’ thinly veiled condemnation of the past four decades of Saudi history, and his call for a more modern relationship between religion and society.

“We are returning to what we were before,” he said, “a country of moderate Islam that is open to all religions of the world. We will not spend the next thirty years of our lives living with destructive ideas. We will destroy them today.”

Writing in Arab News, an English-language daily newspaper published in Saudi Arabia, Maha Akeel, the director of the public information and communication department at the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, provided a wistful vision of that past world, and imagined a better future. “These sentences announce a seismic shift on a grand scale,” she wrote. “For those of us who are too young to remember or who were not born yet, we are told that in the 1960s and 1970s, women went about without covering their hair or wearing a black abaya, and even drove cars; that music and sports were taught at boys’ and girls’ schools; that there were rudimentary cinemas playing Arab and foreign movies…These appear to be tales from a world beyond, but there are black and white pictures and films to prove it all.”

It’s perhaps not surprising that many media reports regarding MBS’ anti-corruption campaign, the proximate reason for the royal purge, and his grand plans for economic modernization have been laced with heavy doses of skepticism and even cynicism. Some reports have questioned whether MBS’ goal is reform or merely a cover for seizing greater authoritarian powers.

It is also accurate to observe that the crown prince isn’t building a parliamentary democracy but is employing authoritarian means, even by Saudi monarchical standards, to set the table for his father’s likely abdication in the months ahead. History is messy, and its protagonists are rarely either perfect or driven in totality by an altruistic vision.

Yet none of that should obscure the possibility that the country that long produced and exported much of Islam’s ideological extremism, a country that for decades seemed impermeable to change, could now have a leader who wants to put Saudi Arabia at the forefront of religious moderation and economic modernization.

In a digital age where the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and extremism have been a magnet for disenchanted youths, outsiders would be mistaken not to embrace this alternative path. Alongside skepticism and anxiety, one senses something rare in Saudi Arabia these past days.

That is a significant whiff of hope.

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

Image: Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (center) attended an allegiance pledging ceremony in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, on June 21. (Bandar Algaloud/Courtesy of Saudi Royal Court/Handout via Reuters)