Fatih Birol, the International Energy Agency’s chief economist, is not prone to hype. So industry executives listen when he calls the surge of U.S. oil and gas production “the biggest change in the energy world since World War II.”

“This is bigger even than the development of nuclear energy,” said Birol in an interview just minutes after he had briefed dozens of the world’s leading energy players and policy makers over breakfast at the fourth annual Atlantic Council Energy and Economic Summit here on the IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2012. “This has implications for the whole world.”

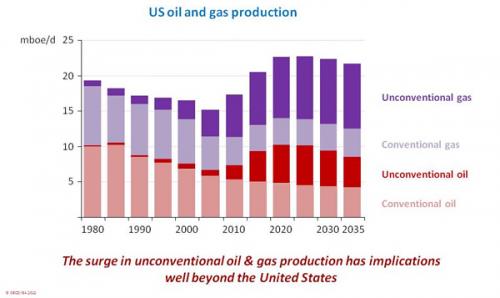

Where Birol lingered longest in his briefing was on a slide, projected for dramatic effect on a giant overhead screen. It was history by PowerPoint, first showing U.S. energy production through 2030 from conventional sources. That scenario left America as a middling producer requiring imports as far as the eye could see. The next two overlays added shale gas and “tight oil” – products of hydraulic fracking, horizontal drilling and America’s God-given geology. According to IEA projections, the U.S. will overtake Russia as the world’s top gas producer by 2015 and will pass Saudi Arabia as the No. 1 global oil producer by 2017. By 2035 the U.S. is likely to be energy self-sufficient and an exporter of oil and liquefied natural gas. Experts are only now beginning to absorb a gusher of geopolitical consequences.

Just when it seemed America’s global influence might be ebbing, the world’s leading military and economic power was adding unconventional energy weapons to its arsenal. The Obama administration – confronting fiscal cliffs, Middle Eastern conflagrations and China’s rise — is only now beginning to understand how to leverage this energy windfall as the president shifts his efforts from re-election to historic legacy.

Those who have despaired about American decline – either relative or absolute — in a world where less democratic and benevolent powers are rising, now hope for an American comeback. Those less inclined toward U.S. leadership worry that this fossil-fuel blessing might reverse the tide toward a more politically humble and environmentally conscious America.

Some of the greatest benefits of the boom could be transatlantic in nature. Several European countries thought to be rich in shale gas resources – Ukraine, Poland, Romania and Bulgaria – have paid a considerable commercial and political price for their continued dependence on Russian gas at a time when a European Union anti-trust action against Gazprom has only deepened tensions. That said, Europe has been slow to embrace unconventional gas and oil extraction; France has a moratorium on fracking, and environmental groups are slowing development elsewhere.

Here’s where concerted U.S. government and private-sector support could pay rich dividends, diversifying Europe’s energy sources and winning new markets for U.S. extractive and environmental technologies. David Goldwyn, a former U.S. State Department special envoy for international energy, wrote in the New York Times that the U.S. “should assist others who want to develop their own resources … by helping their governments put in place the fiscal, environmental and safety regimes necessary to facilitate the growth of robust domestic markets.”

Gulf Arabs are particularly concerned about the potential impact of an energy-self-sufficient America on their interests. Despite Obama administration reassurances, they doubt whether the U.S. will be as reliable a provider of security if its energy dependence shrinks even while risks proliferate: nuclear-fueled Iranian expansionism, simultaneously growing Shiite and Sunni extremism, Egyptian democratic fragility and rising Israel-Palestinian violence.

The IEA projects that U.S. oil imports from the Mideast will decline to virtually nothing over the next decade, while China’s dependence expands rapidly. By 2035, some 90 percent of Mideast exports will land in Asia, the IEA projects. Over time, Beijing will question the wisdom of relying entirely on the U.S. to secure its energy shipping lanes from the Gulf, and U.S. taxpayers will question why they are paying for the Fifth Fleet to do the job. Energy interests have a tendency to redefine military alliances.

Yet the Chinese dimension goes further than that. China has shale gas reserves equal to or larger than those of the U.S., though they haven’t yet been exploited. Following an agreement reached by Obama on his first trip to China in November 2009, the U.S. is helping the Chinese in areas ranging from exploration to environmental protection. At the same time the China National Offshore Oil Corp. is purchasing Canada’s Nexen Inc. for $15.1 billion, an acquisition aimed at acquiring shale gas technology, and other Chinese companies are following suit.

The most immediate impact of the shale-gas bonanza has been on America itself. “Most important, it means that the many people who had written off the U.S. economy have made a big mistake,” says Birol. “The U.S. current account deficit is declining, there will be downward pressure on inflation and the dollar will strengthen.”

As Daniel Yergin wrote in the Financial Times, these new energy sources have created more than 1.7 million U.S. jobs, and by 2020 those numbers could grow to 3 million. New taxes and royalties could amount to more than $110 billion by that time, providing urgently needed resources for cash-strapped governments. At the same time, historically low U.S. natural gas prices, which are a third of those in Europe and Japan, are prompting billions of dollars of investments in U.S. advanced manufacturing – thus fueling a new export economy.

During the U.S. election campaign, Australian Foreign Minister Bob Carr famously said America “was one budget deal away from restoring its global preeminence.” Factor energy into that picture, and President Obama has all the makings for a historically successful second term.

Fred Kempe is the president and CEO of the Atlantic Council. This column was originally published by Reuters.

Image: pa_shalegas.jpg