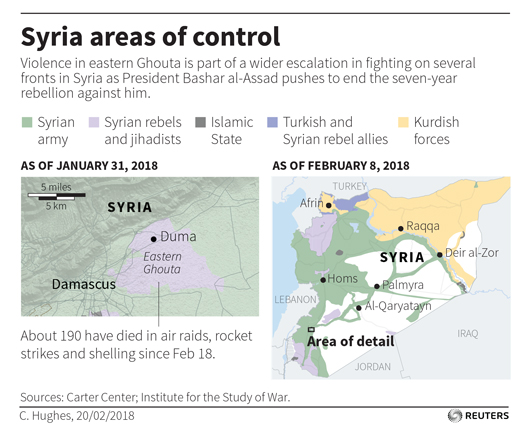

Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s forces have unleashed an unrelenting bombardment of the rebel-held Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta that has killed hundreds—many of the victims are women and children—over the past few days.

Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s forces have unleashed an unrelenting bombardment of the rebel-held Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta that has killed hundreds—many of the victims are women and children—over the past few days.

The United Nations (UN) has warned that the situation is “spiraling out of control.” The Assad regime has reportedly not even spared hospitals and schools. Targeted attacks on these locations could be tantamount to war crimes.

Residents of Eastern Ghouta are living in grim humanitarian conditions marked by extreme food shortages, astronomical food prices, and scarce medical supplies.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a United Kingdom-based monitor group, said the ongoing attack on Eastern Ghouta is the deadliest attack in that location since a chemical attack by the Assad regime in 2013. The war in Syria is now in its eighth year.

Frederic C. Hof, director of the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, discussed the developments in Syria in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from our interview.

Q: What is happening in Eastern Ghouta?

Hof: In Eastern Ghouta, the Assad regime and its external enablers—Russia and Iran—are plying a political survival strategy that they believe has worked in the past. That is a strategy of state terror featuring mass homicide of civilians in an effort to separate a civilian population from armed rebels and compel the surrender of the rebels through mass murder.

Q: What are conditions like on the ground?

Hof: There have been hundreds of civilian casualties.

There is no evidence at all that armed rebels have been targeted in any specific manner. Instead, the approach is one of collective punishment. All manner of conventional weaponry—both air and artillery—have been used to reduce residential areas to rubble. The [Trump] administration’s chemical red line has been crossed repeatedly by the weaponization of chlorine in the form of canisters packed into barrel bombs that are otherwise filled with shrapnel.

Q: What is the Trump administration’s position on the use of chemical weapons in Syria?

Hof: The Trump administration has made it clear that the use of chemical weaponry is inadmissible and that it retains the right to respond forcefully to such use. It did so once in April 2017 when the sarin nerve agent was deployed by the Assad regime against the inhabitants of a Syrian town.

What Assad himself seems to have calculated is that he can cross the red line at will provided there is no nerve agent involved in a particular operation—that the weaponization of chlorine, from Assad’s point of view, is safe.

Q: Eastern Ghouta was the site of a chemical weapons attack by the regime in 2013. Is there any evidence that chemical weapons have been used again in this Damascus suburb?

Hof: Other than weaponized chlorine, I am not aware of reports of other chemical agents such as sarin.

Sarin is clearly still being stockpiled by the Assad regime notwithstanding the chemical agreement reached by the United States and Russia in 2013.

Q: What specific support are Assad’s forces receiving from the Russians and the Iranians in their offensive on civilians in Eastern Ghouta?

Hof: There is a consistent flow of reports saying that Russian combat aircraft are involved in the assaults on residential areas in Eastern Ghouta.

In my view, [Russian] President [Vladimir] Putin’s December announcement of a drawdown and eventual withdrawal from Syria has not translated into facts on the ground. Indeed, he may have made that announcement as a sort of insurance policy, given the fact that there are Russian presidential elections coming up in March. Putin wants to assure the people of Russia that “mission accomplished” is in sight, that Russia has not waded into a quagmire, and that Syria—as a general matter with the preservation of Bashar Assad—represents Russia’s return to the stage as a great power. This is basically what Putin tells his domestic audiences.

Q: What can the international community do to stop the bloodshed in Eastern Ghouta?

Hof: If we are talking about stopping the bloodshed, there is nothing that can be done that is of a risk-free nature.

The Trump administration demonstrated in April 2017 that the use of sarin nerve agent can be stopped. It demonstrated that by eliminating an estimated 20 percent of the Syrian air force by using cruise missiles against the air base from which the sarin attack was launched.

Any effort to stop what is happening in Eastern Ghouta has to involve something along those lines.

Q: But how can that goal be achieved without escalating the war when Russian aircraft are involved in the bombardment of Eastern Ghouta?

Hof: That obviously complicates matters. It would have been far preferable if people on the ground in Eastern Ghouta had been given a chance at self-defense in the form of anti-aircraft weaponry. A Russian plane was brought down recently in northern Syria by a surface-to-air missile.

Russian aircraft are located at one principal air base in Latakia province in the northwestern part of Syria. I think the [Trump] administration has the ability to explore the possibility of hitting bases where Russian aircraft are not present.

Q: What other major developments are taking place in the war in Syria?

Hof: It is a multifaceted war.

In Syria, east of the Euphrates River, the United States is trying to come up with a stabilization formula in areas liberated from ISIS [the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham]. If the objective is not only to kill ISIS in eastern Syria, but to keep it dead, there has to be follow-on stabilization that provides for basic governance, law and order, the inflow of humanitarian assistance from the United Nations, and at least the beginning of a reconstruction of basic infrastructure. It seems that the Trump administration takes this requirement of post-combat stabilization seriously.

There was an attempt not long ago by a pro-regime force, apparently containing a large number of Russian mercenaries, to ford the Euphrates River deconfliction line and move in the direction of oil fields held by the anti-ISIS coalition. That attempt was met by force, mainly in the form of US air power, and there were reports of several dozen Russian individuals being killed and wounded in the attack.

Elsewhere, we have the ongoing saga of Turkish intervention in the Afrin district in northwestern Syria, which seems to be getting more and more complicated with every passing day. The Turks and the ground force of Syrian rebels that they are employing in this operation are finding it very, very difficult due to a combination of weather, terrain, and the skills of Kurdish [People’s Protection Units] YPG fighters to make significant progress in Afrin.

This has not been a walkover and it has been understandably difficult. Among other things, it is very difficult for vehicles to move through deep mud. So, this has been very, very slow going.

Now there are reports of Assad having dispatched pro-regime militiamen to Afrin to confront the Turks and the Turks’ Syrian allies on behalf of the Kurdish YPG. There are also reports of Turkish artillery having interdicted some vehicles associated with that intervention.

Q: What do these blurred battle lines mean for the war?

Hof: Northern Syria presents the possibility of a more and more complicated battle involving the various parties that have played a role in this conflict.

The YPG is the key element of the ground combat component of the US-led battle against ISIS in eastern Syria. As the YPG has established itself in pockets along the Turkish border, well to the west of the Euphrates River, it has from time to time collaborated with the Assad regime on an opportunity basis to try to consolidate its role.

The United States obviously takes a dim view of the Assad regime, but this, in addition to the Turkish attitude toward the YPG—which is that the YPG is a terrorist organization and the Syrian arm of the PKK [Kurdistan Workers’ Party]—complicates matters tremendously.

The YPG is still a key element of the US-led partner force in Syria east of the Euphrates River. West of the Euphrates, and in particular in Afrin district, it is something else. It is some of the same people. Kurds in eastern Syria who have been confronting ISIS have in some number left and joined the fight in Afrin.

This is all part of a very complex situation that is further complicating efforts of the United States to try to get on the same page as Turkey with regard to Syria.

Frederic C. Hof is director of the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. Follow him on Twitter @FredericHof.

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

Image: A man carried an injured boy in the rebel-held town of Hamouriyeh in Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus, Syria, on February 21. Bashar Assad's forces have unleashed an unrelenting bombardment of the Damascus suburb that has killed hundreds of people. (Reuters/Bassam Khabieh)