Atlantic Council’s Pham says President Salva Kiir must step down to give his country a chance

Four years after it won independence from Sudan following decades of war, South Sudan is once again trapped in a vicious cycle of conflict that has turned the world’s youngest nation into a failed state, says the Atlantic Council’s J. Peter Pham.

South Sudan was plunged into the crisis in December 2013 following a power struggle between its President, Salva Kiir, and his deputy, Riek Machar, whom he fired and later tried to arrest, alleging a coup attempt. The United States says it has seen no evidence of such a plot.

South Sudan became independent on July 9, 2011.

“Africa’s youngest country, and the world’s newest country, was born with an incredible amount of goodwill, incredible promise. That promise has not been kept and the goodwill has been squandered by the conflict that the political elites of South Sudan allowed to foment and then to break out into open civil war,” Pham, Director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center said in an interview.

The war has killed tens of thousands, displaced more than two million people, and pushed South Sudan into a humanitarian crisis that has been marked by rampant food insecurity.

Kiir must step down as President if South Sudan is to have any hope of extricating itself from this dire situation, says Pham.

J. Peter Pham spoke in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts of that interview:

Q: Four years since its independence from Sudan, how is South Sudan faring as a country?

Pham: If one is honest, there is probably no greater disappointment to the many people, policymakers, analysts, and advocates who for many years kept the attention on the conflict in Sudan and who fought to secure for South Sudan the opportunity of self-determination through the referendum in 2011, than what has happened.

Africa’s youngest country, and the world’s newest country, was born with an incredible amount of goodwill and incredible promise. That promise has not been kept and the goodwill has been squandered by the conflict that the political elite of South Sudan allowed to foment and then to break out into open civil war.

The country is now not only the world’s youngest nation, it is also what is arguably its most failed state. The conflict that broke out in December 2013 has killed tens of thousands; displaced well over two million people, internally and externally as refugees; and currently leaves probably a third of the population of about 11 million in grave danger of not only food insecurity, but of facing potentially catastrophic famine in the course of the next year.

Q: Former Vice President Riek Machar wants President Salva Kiir to step down. He blames Kiir for violating multiple ceasefires. Can South Sudan move forward with its current cast of leaders?

Pham: Certainly there is blame to go around, not only between the two main parties to the conflict, but the regional actors as well as the international community. That being said, however, when one occupies a position of authority as a legal government one is held to a higher standard. I would argue, as I have in the past, that Riek Machar is correct insofar as his analysis that Salva Kiir has to go.

Salva Kiir as President precipitated what was a political crisis by firing his vice president and other leaders. Then he exacerbated the situation, turning a rivalry between politicians into an armed conflict by attempting to claim, without any evidence, an alleged coup attempt to justify eliminating his opponents. However, if you’re going to try and physically eliminate your opponents, you had better do get it right the first time. He tried to stage a night of the long knives, but he didn’t even bring a penknife to the fight. That type of criminal incompetence turned a political dispute into a civil war. That level of sheer idiocy alone disqualifies him going forward.

In a speech at the Atlantic Council last October, US Special Envoy for Sudan and South Sudan Donald Booth laid out a realistic position for the United States. It is, I think, a very prudent position: the fact that we’re interested in a transition, we’re interested in a way forward, and we do not have any favorites as to who will lead that transition.

There is no default position that says Salva Kiir needs to stay. I am going to argue that perhaps he needs to go. But I also think Machar has a great deal to answer for even if he didn’t start the conflict, certainly for the conduct of the conflict. The important thing is to move forward with a process that will enable real political dialogue rather than simply cementing someone in place.

Q: What can the international community—the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the US, the UN—realistically do to put pressure on Salva Kiir and Riek Machar to resolve their conflict?

Pham: I am a little more optimistic of the negotiating process now than I was several months ago because the international community has finally come to the realization that the IGAD-led process was fatally flawed.

IGAD, the sub-regional African body, included South Sudan as a member. So one of the parties to the conflict, Salva Kiir as President of South Sudan, participated in meetings of the group that was supposed to be mediating the conflict. Needless to say that was a no starter and IGAD was unable to overcome that obstacle.

The reinvigorated process, which brings in the international community, the African Union, and other actors, potentially helps bridge that impasse.

Another party to the conflict, Uganda, which has sent troops to prop up Salva Kiir, was part of IGAD, as was Kenya, which had turned a blind eye to the comings and goings of people on both sides of the conflict. So the IGAD mediators up to now didn’t succeed because, not having entirely clean hands, they lacked credibility.

Another problem was sanctions. The United States and the United Nations have tried to be evenhanded and sanctioned three relatively minor leaders on both sides of the conflict. That is not going to get anything moving if the only people punished are lower-ranked leaders who are unlikely to have assets to freeze or international travel plans.

First one has to have real sanctions against people who really are in power. Then we have to buy-in of the countries in the region to enforce the sanctions. The fact is that on both sides of the conflict their leaders have homes in different countries, especially, Nairobi.

And, finally, we need a real arms embargo. Arms continue to flow into South Sudan to both sides of the conflict.

Q: On the point of an arms embargo, the United Nation’s peacekeeping chief has urged the UN Security Council to impose an arms embargo on South Sudan and to blacklist more rival leaders. What is holding that up?

Pham: A combination of factors. Part of it is political will on the part of the international community. There are many people, including in our own country, who look at South Sudan rather than through the clear lenses of realpolitik, through rose-tinted lenses from their years in advocacy.

Regional countries, Kenya in particular, not only allow leaders on both sides of the conflict and their families to come and go, but in the past year have allowed large arms shipments to go—while there is no formal arms embargo, but certainly there was an appeal by the United Nations and by various members of the international community to cut off arms—from China to Salva Kiir’s side of the conflict. That is unhelpful. You also have Ugandan forces fighting to defend Salva Kiir.

Q: Besides war, South Sudan is also facing a large humanitarian crisis. Will this crisis only get worse?

Pham: Right now there is a lull in the crisis that is deceptive. The lull is mainly meteorological. This is the rainy season, which makes most of South Sudan impassable. When tracks and fields become passable armed conflict will resume.

In the meantime, the rains are making humanitarian assistance that much more difficult. The worst part is that due to the insecurity farmers are not planting. According to the United Nations, a third of the people in South Sudan are food insecure. One anticipates that over the course of the next year that food insecurity could easily metastasize into full-blown famine.

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

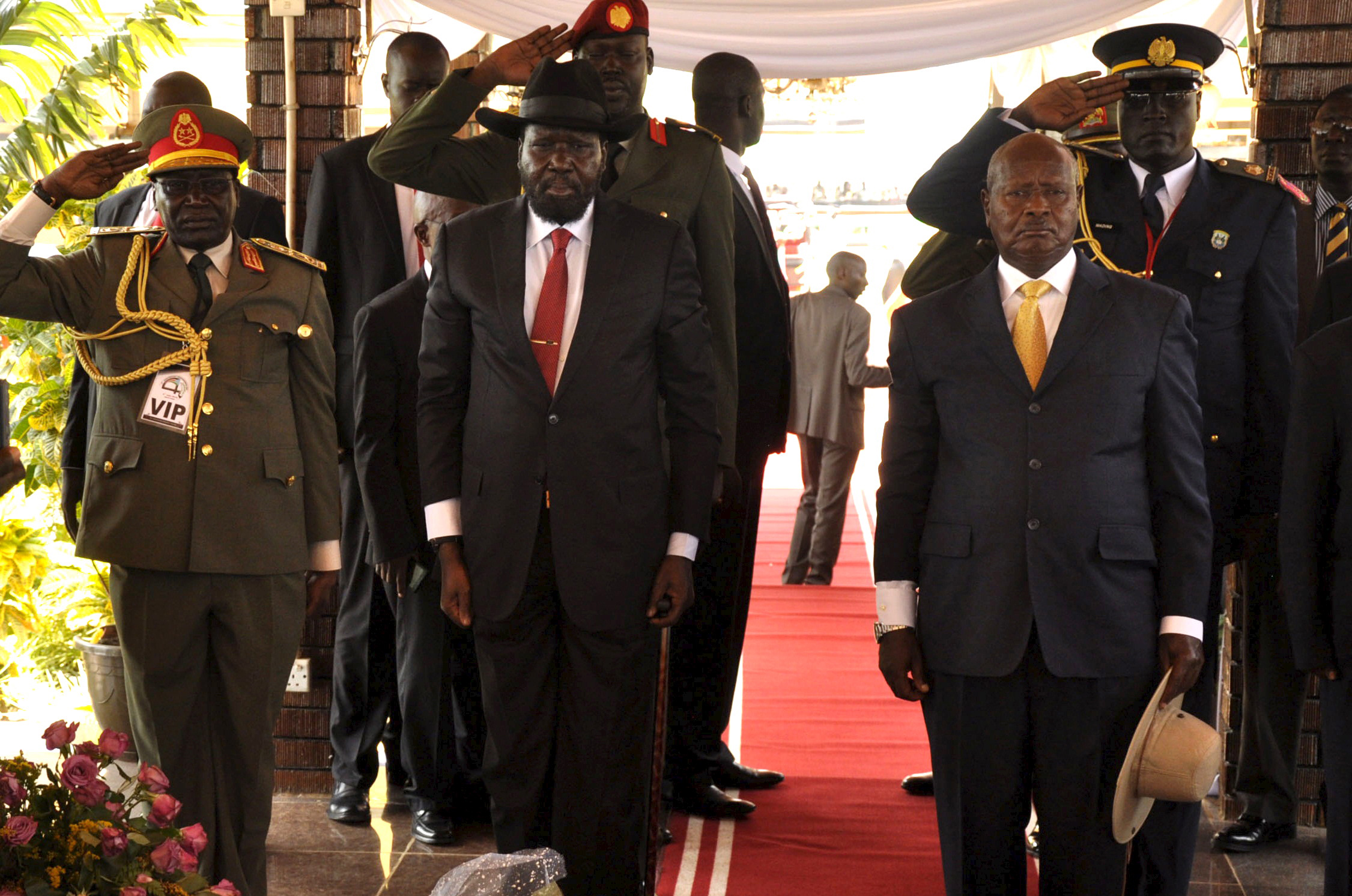

Image: South Sudan's President, Salva Kiir (center), and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni (right) pay their respects at the mausoleum of Sudanese rebel leader John Garang during a ceremony to celebrate South Sudan's fourth independence day in the capital Juba July 9 (Reuters/Jok Solomoun)