Amid recent chaos in Congress, it is often difficult to see the progress being made on any area of legislation. However, beneath the fractious noise and political posturing, some inhabitants of the Hill have been diligently working toward bipartisan legislation in a critical area of US foreign policy that deserves a brighter spotlight—export control reform.

For decades, some of the United States’ closest allies have been quietly frustrated by the indiscriminate and extraterritorial application of US export controls, which seriously hinders efforts to share technologies and collaborate on capability development projects. In particular, the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) has drawn the ire of allies for restricting the export and import of certain defense products. As one of the authors explained in June, and with no criticism toward the hardworking State Department officials who have dedicated their careers to keeping the nation’s most critical technological advancements out of enemy hands, the current legislative and regulatory regimes are not structured to support the pace or flexibility that modern technology and the strategic competition with China demands.

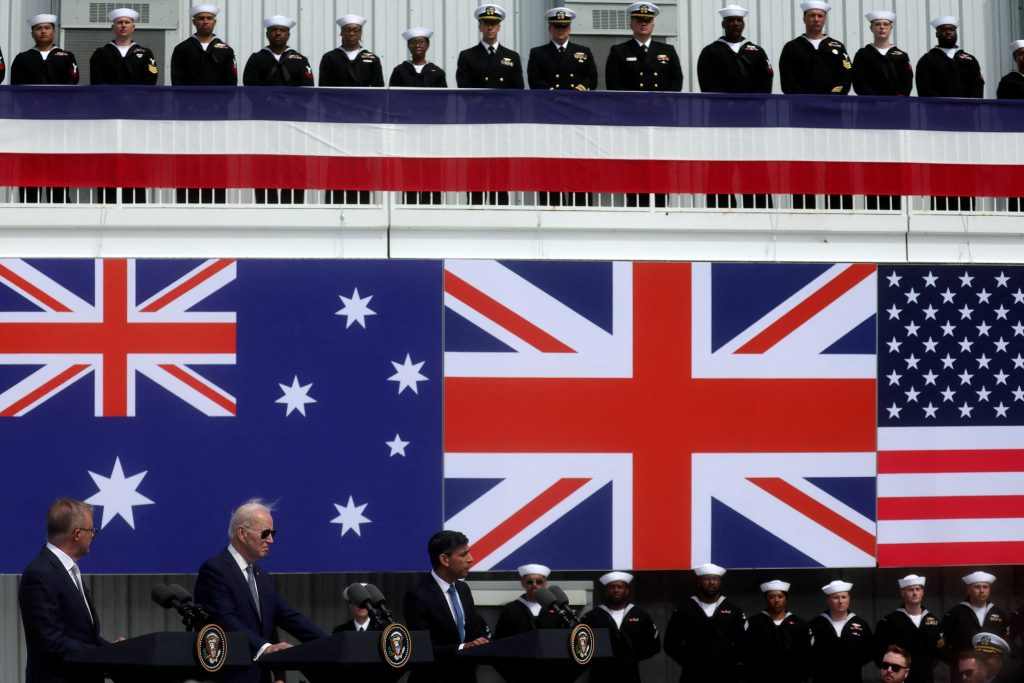

It is fortunate then that AUKUS, the trilateral partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, has driven an unprecedented state of urgency into the discussion. Politicians and policymakers in all three nations—and on both sides of the aisle in the United States—now recognize that the partnership just won’t stand with ITAR as it’s currently enforced. This is particularly clear when it comes to the wider cooperation envisaged in AUKUS for critical technologies, including those dealing with artificial intelligence, autonomy, cybersecurity, and electronic warfare.

Progress at last

Positive movement on the issue first started to appear in summer of this year, when UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and US President Joe Biden jointly announced the Atlantic Declaration, which included modernization of export controls as part of a broader US-UK economic partnership. Since then, both the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the House Foreign Affairs Committee have passed provisions aimed at legislating an ITAR exemption for AUKUS nations. That language choice is important, as any exemption which was narrowly applied to AUKUS projects would cover only a very minor portion of collaborative development among the nations and, at best, provide limited benefit in terms of removing the unnecessary delays and compliance costs which currently cause so much pain.

Some policy experts who watch this legislation closely say that Congress now stands closer to truly reforming ITAR than it ever has before. However, the differing approaches between the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and House Foreign Affairs Committe mean that a compromise bill must first be agreed through a bicameral conference committee before it can proceed. The need for a compromise bill, chaos in the House of Representatives, and continued congressional disagreement over federal spending mean there is no sign of a full floor vote in either chamber any time soon.

AUKUS is fundamentally a partnership for deterrence, and no one except for the partnering nations’ adversaries benefits from delay and continued uncertainty. The United States and its closest allies have a generational opportunity to work together to combat the increasingly dynamic threat posed by common adversaries. Allowing it to fall away because of legislative complications in one nation would be a failure of enormous magnitude. Both houses of Congress must stay the course and pass legislation for an AUKUS nations ITAR exemption as soon as possible.

Half the battle

As is often the case in Washington, legislation is only a first step. Even if a compromise bill results in the holy grail of an ITAR free transfer zone among the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and their respective industrial bases, then it will only be the beginning of the story. Many previous attempts at export control reform have failed in implementation, as other experts have pointed out. Once legislation is passed, new regulations must be written, the State Department must implement and enforce them, and the defense industries in all three nations must be willing and able to use them.

There are three areas of implementation which will require particular attention if an AUKUS exemption is to succeed. These are the scope of the exemption, the mechanisms through which industry partners can use the exemption, and the definition of “comparable standards.”

Taken in reverse order, it is almost certain that the legislation will require the United Kingdom and Australia to demonstrate that their export control regimes protect sensitive technologies to a standard that is comparable to the US regime. For the United Kingdom, this should be relatively simple, as the country has a long history of cooperation with the United States on the most sensitive of defense technologies, including nuclear propulsion and weapons development. Moreover, the United Kingdom already has a strong defense industry of its own, which develops sensitive capabilities and has a proven record of protecting US technologies. The United Kingdom also already has a robust export controls regime, which has been further reinforced in recent years through the 2021 National Security Investment Act, which significantly strengthened existing legislation on investment security, and a more recent expansion of military end-use controls, which broadened the scope and number of countries to which exports can be blocked. The United Kingdom’s forthcoming National Security Act will also strengthen protections around intangible exports already in place under the 1989 Official Secrets Act.

Australia is in a slightly different position, as its defense industrial base is much smaller and its exports are far more modest, meaning that it might be harder to demonstrate a sustained level of comparable protections. But it does already have a domestic export controls regime in the Defence Trade Controls Act of 2012, and is currently consulting on amendments to strengthen the Act, including by creating three new criminal offenses. Australia, like the United Kingdom, is also party to multilateral export control regimes, including the Missile Technology Control Regime, and voluntarily submits to end-use monitoring of items.

So, while there may be specific areas that need tightening up, there is no defensible need for either the United Kingdom or Australia to follow the example set by Canada in the early 2000s and overhaul their existing export control regimes to exactly match the United States. This is primarily because “comparable” does not mean identical, but also because it doesn’t exactly set the right tone of trusted partnership for the United States to demand other sovereign nations change their domestic laws to suit itself. Practically speaking, even if the UK or Australian government was willing to change its domestic laws in this way, any change requiring primary legislation to enact would take time to pass through its respective parliament and would introduce further, unnecessary delays. The key implementation questions here for partner nations are how, and by whom, the comparable standards criteria will be judged, how quickly that decision will be made, and how many hoops they will be willing to jump through to get the green light.

The other two issues—the scope of the exemption and the mechanisms through which industry partners can use it—are interlinked and relatively straightforward, but just as critical. In today’s world of private sector-dominated research, which produces technologies that are increasingly dual-use, industry and academia are crucial partners in defense capability development. Any exemption that these partners are unwilling to use because the risk is too high or are unable to use because the processes are too burdensome will be dead on arrival. This has happened in previous attempts to reform export controls, such as the Defence Trade Cooperation Treaties of 2007, with their overly complicated carve-outs and sign-up processes, and the more recent Open General License Pilot, which applies only to the “maintenance, repair, or storage” of a narrow range of existing technologies and is therefore almost entirely ineffectual. Moreover, the US military may be left guarding second-tier capabilities while the commercial domain races ahead with unclassified and commercially available best-in-class alternatives. This is particularly likely in the realm of software development.

These examples of past failures highlight the critical importance of clarity of scope and ease of access in delivering a workable exemption. In designing its implementation and enforcement approaches to any new exemption, the State Department should consult with the United Kingdom and Australian governments, but also with partners in industry and academia. It should ensure that the mechanism to sign up to use the exemption is as straightforward as possible, that reporting and audit processes are appropriate to the relatively low levels of security risk involved, and that there is no uncertainty regarding the scope of technologies that are covered. It is especially important that the new approach does not inadvertently introduce a dual-track system, in which some areas of technology development cooperation are covered and others are not.

If the AUKUS experiment is to live up to its promise of allowing the closest of allies to genuinely work hand in hand to advance global security into the second half of this century, then Congress and the Biden administration must both show that they are willing to make the necessary changes to a needlessly limiting export control regime that, in this case, does more harm than good. Let’s all hope they are up to the challenge.

Deborah Cheverton is a visiting senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Forward Defense program within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

John T. Watts is a nonresident senior fellow in the Forward Defense practice of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and head of US federal coordination at Cocoon Data.

Note: This piece has been updated to correct John Watts’s employer.

Further reading

Wed, Jun 7, 2023

Export controls: A surprising key to strengthening UK-US military collaboration

New Atlanticist By Deborah Cheverton

US allies have been quietly frustrated for decades about the indiscriminate and extraterritorial application of export controls, in particular the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).

Tue, Mar 14, 2023

What’s next for the US-UK-Australia submarine partnership?

New Atlanticist By

Dive into the details of the AUKUS submarine partnership just announced in San Diego by US President Joe Biden, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

Wed, Aug 16, 2023

The United States and its allies must be ready to deter a two-front war and nuclear attacks in East Asia

Report By Markus Garlauskas

This report highlights two emerging and interrelated deterrence challenges in East Asia with grave risks to US national security: 1) Horizontal escalation of a conflict with China or North Korea into simultaneous conflict; 2) Vertical escalation to a limited nuclear attack by either or both adversaries to avoid conceding.

Image: US President Joe Biden, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak deliver remarks on the Australia - United Kingdom - US. (AUKUS) partnership, after a trilateral meeting, at Naval Base Point Loma in San Diego, California U.S. March 13, 2023. REUTERS/Leah Millis