Ever since the beginnings of the modern petroleum industry in Azerbaijan in the mid-19th century, the country has, despite being a major oil exporter, also been a net gas importer.

It was only recently that production from Phase I of the Shah Deniz gas-condensate field picked up, along with output of associated gas at the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli (ACG) field. Several smaller fields operated by SOCAR, the national oil and gas company, have also contributed. For the first time in its history, in 2007 Azerbaijan was able to discontinue gas imports from Russia and begin exporting to Turkey via the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP). So far, exports have run at a low level, well below SCP’s initial capacity of 6.7 billion cubic meters per year (bcmy), which will eventually be increased to 20-22 bcmy. However, with the removal of major impediments to exports of gas from Azerbaijan to Turkey, exports will rapidly grow – to Turkey and beyond. If only Azerbaijan and Turkey could come to an agreement.

Negotiations between Azerbaijan and Turkey have been dragging on primarily because the two sides could not agree on the price, volume, and terms and conditions for transit of Azeri gas via Turkey. Under the previously signed contract for export of up to 6.6 billion cubic meters per year (bcmy) of gas to Turkey, the price was set rather low, at $120 per 1,000 cubic meters, even though it could be renegotiated once per year. Besides, BOTAS, the Turkish gas company, insisted on buying Azeri gas and then reselling it to customers in Europe, a policy which prompted some observers to note the emergence of “Gazprom lite”.

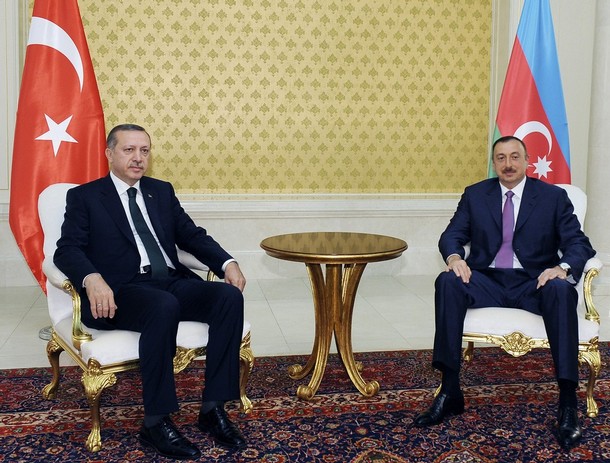

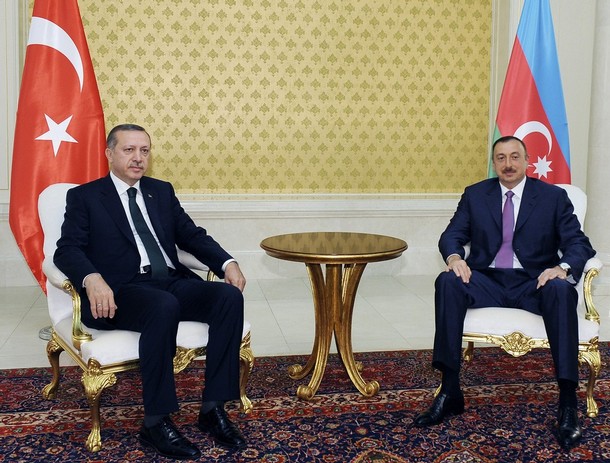

These issues should have been resolved during the recent visit of Turkey’s PM Recip Tayyip Erdogan to Baku, where he discussed with President Aliyev of Azerbaijan the gas price, a visa deal, and the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute. It was expected that the gas agreement would be signed on May 17, during the visit, but surprisingly the deal was postponed due to undisclosed “minor technical issues.” It is now scheduled to be closed in early June in Istanbul, where Turkey plans to hold a gas summit with EU participation. Reportedly, the delay is more pomp than circumstance, as the actual contract between SOCAR and BOTAS has been put to paper and is now just waiting for the ink during a nicely appointed occasion.

Hopefully, the delay will be the last one. At stake is not just Nabucco, which has so far failed to subscribe suppliers of gas, but also Turkey’s credibility and ambition to become a gas hub serving the Balkans and Europe, along with Azerbaijan’s long term position as an exporter of natural gas.

Most of the oil and almost all of the gas produced in the Caspian basin still reach international markets via pipelines across Russia. Russia buys most of Turkmenistan’s gas, all of Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s, and has offered to do the same with Azerbaijan’s gas. The absence of direct outlet to international markets has delayed the development of the Shah Deniz field in Azerbaijan and stripped the country from a new major source of export earnings. Nabucco has also suffered, since Iran, which often plays along with Russia in the Middle East, is currently the only other potential source of gas for the pipeline.

Some of the delay was caused by geopolitical factors. Turkey’s recent move to reconcile with Armenia was met with consternation in Baku, which seeks to orchestrate regional energy and cooperation projects in a way that bypass Armenia. The delay may actually hurt Azerbaijan more than anyone else, since without an outlet to markets it will be impossible to proceed with Shah Deniz II, now due in 2017. Turkey has requested 6-7 bcmy from Shah Deniz II, which will produce an additional 16 bcmy on top of the current 9-10 bcmy from Shah Deniz I. That would make available some 10-12 bcmy of gas per year to Nabucco, still quite short of its ultimate capacity of 31 bcmy, but possibly just enough to proceed with the project.

But Nabucco is not the only way to take natural gas from Turkey to Europe. On May 20, Germany’s E.ON Ruhrgas joined the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) project along with Norway’s Statoil (which also participates in Shah Deniz and SCP) and Switzerland’s EGL. The project will deliver gas from Greece (which is already connected to Turkey by a 36 inch pipeline) to Italy. The move peeved both the Nabucco partners, who now include Germany’s RWE, and the participants in the Italy-Greece-Turkey Interconnector project (ITGI), a project that also aims at bringing Caspian gas to Italy via Turkey and Greece. ITGI is promoted by Italy’s Edison, Greece’s DEPA, and Turkey’s BOTAS, and Bulgaria’s Bulgargaz has expressed desire to join it. However, only Nabucco, in which BOTAS participates as well, will commit itself to developing the extra transiting capacity in Turkey that is needed for any of these projects to succeed.

In the puzzle, Azerbaijan and Turkey remain the key. During the “gas summit” which convened in Prague in May 2009, EU offered trade and transport facilities to the two countries so that the so-called “Southern Corridor” could become a viable avenue for exports of Caspian oil and gas. At the time, European Investment Bank President Philippe Maystadt said the bank has held funding talks with the consortium behind Nabucco and those behind the two other proposed pipelines to bring Caspian gas to Europe — the TAP pipeline and the ITGI. Options for bringing gas into Turkey from Iraq and Egypt were also considered.

In early June in Istanbul, another gas summit will convene and another milestone may be passed. Keep your fingers crossed.

Dr. Boyko Nitzov is Director of Programs and Galib Abbaszade is an intern for the Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Energy Center at the Atlantic Council. Photo credit: Reuters Pictures.

Image: turkey-azerbaijan-gas-talks.jpg