Do Chinese leaders really react more strongly to external provocations in the runup to sensitive political events, such as last month’s Twentieth Party Congress or the National People’s Congress scheduled for March?

Milestones like this party congress, party plenums, or even leaders’ informal conclaves at the Beidaihe resort do heighten Beijing’s determination to control domestic narratives and security in advance of these gatherings. Thus, it is logical to assume that this sensitivity also shapes Beijing’s responses to crises and challenges from abroad. But in practice, there is little connection between the timing of these events and the strength of Beijing’s responses to external provocations.

Global policymakers contemplating the timing of their own major decisions that affect China have nothing to gain by deliberately poking Xi on the eve of a political event. But they shouldn’t distort their timetables out of a misplaced fear of provoking a disproportionate reaction.

Case in point: US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s August visit to Taiwan. Analysts warned that the party congress that followed just months later would affect Beijing’s reaction to the visit but were hard-pressed to predict how. Some observers speculated that Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping would feel pressure to respond more forcefully to burnish his image while others predicted he would instead temper his response to minimize instability during a sensitive period. In the end, Beijing’s military exercises, punitive economic measures, and rhetorical responses were consistent with its longtime strategy of gradually but steadily increasing pressure on Taipei. There was little evidence that domestic pressure had affected Beijing’s response in either direction.

Three interrelated factors explain why Beijing’s domestic sensitivity in the runup to events like the Twentieth Party Congress doesn’t translate to significantly sharper reactions to foreign provocations such as Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan: Xi’s unassailable authority, his grip on foreign policymaking, and his character as a decisionmaker.

Unquestioned authority—and supreme narrative-shaping

Xi’s dominant political position, which was solidified last month as he packed top posts with loyalists at the party congress, allows him to respond to foreign-policy challenges based on his preferences and strategic calculations without fearing the reaction from CCP elites. Xi’s successful effort to make his personal authority a core tenet of the party’s guiding ideology has robbed disgruntled elites of the ability to oppose his policies without also exposing dangerous cracks in the basis of the party’s legitimacy. Thus, even after Xi’s handling of contentious issues such as the trade war with the United States, Taiwan policy, or COVID-19 containment measures created openings for criticism, there is no evidence that the leader’s control has been dented or challenged.

Xi’s ability to control popular sentiment is more difficult to gauge, but the party’s relentless efforts to control the domestic information environment give him a potent tool to deflect criticism. Xi’s control over domestic narratives through the information environment can be seen in the aftermath of skirmishes between the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and Indian forces in 2020. During one of the skirmishes, the PLA suffered its first combat deaths in decades (which Beijing officially acknowledged months later); but Beijing successfully suppressed unwanted discussion about the clash, and there was no sign that public pressure altered the CCP’s approach to the border clashes. While China’s disputes with India have far less political and emotional resonance with the public than disputes with Taiwan or the United States, the complete dearth of domestic pressure following PLA soldiers killed in action demonstrates Xi’s ability to shape domestic narratives.

The impact of centralized decision making

Xi’s insistence on remaining “chairman of everything” and claiming sole leadership of the CCP’s key national security-related organs means that Beijing’s major foreign policy decisions require his approval and then carry his personal imprimatur. This probably constrains the range of permissible debates among other leaders and officials and motivates them to compete to implement Xi’s guidance most effectively, rather than to promote the boldest policy proposals. Thus, officials are incentivized to echo and reinforce Xi’s views and inclinations, which are often calculating and careful.

Guided by calculation, not sentiment

Xi’s response to foreign-policy challenges has been guided by his calculation of long-term interests rather than personal sentiment or resentment about ill-timed provocations from abroad. Under Xi, Beijing’s foreign policies generally have adhered to coherent and consistent strategic principles. Those principles have sometimes been misguided and those decisions have sometimes derived from miscalculations, but they have not been capricious.

For example, in the months leading up to the Nineteenth Party Congress in 2017, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un launched an intermediate-range ballistic missile hours before Xi presided over the first Belt and Road Forum, which gathered leaders from Russia and Central Asia and was an important part of Xi’s first-term legacy. Then in September, Kim again upstaged Xi by conducting a nuclear test hours before Xi addressed the leaders of countries that are part of the BRICS grouping of developing economies—and just a month before the Nineteenth Party Congress.

Yet whatever ill will Xi may have felt proved no obstacle to the subsequent careful rapprochement between Beijing and Pyongyang. Kim visited China repeatedly between 2018 and 2019, with the first trip happening just after the close of China’s National People’s Congress; Xi visited Pyongyang a year later. His appraisal of China’s strategic imperatives trumped any resentment he may have felt about Kim’s missile and nuclear activities—activities that probably are the most deliberate foreign attempts to undermine Xi’s political choreography that the Chinese leader has ever faced.

Policymakers: Watch Xi’s calculus, not his calendar

This all suggests that the salience of China’s political calendar in influencing Beijing’s responses to crises and challenges from abroad varies by issue and decisionmaker. Most decisions about major foreign-policy provocations will land on Xi’s desk, and he will likely respond based on a long-term calculus. He is unlikely to feel pressure to either lash out to placate domestic audiences or shy away from confrontation merely to preserve stability during a sensitive period.

However, the implications are different when China’s reaction to a policy falls within the purview of second-tier decisionmakers, who are much more exposed to criticism from peers if they fail to prevent embarrassing incidents during a sensitive period. A Chinese ambassador posted to a country that Beijing considers to be of peripheral importance, for example, may have substantial leeway to shape policies or commercial arrangements and will be motivated to avoid embarrassment. Actors at this level may be more likely to quietly offer inducements or issue threats to foreign counterparts before major political events in Beijing.

One corollary is that events like the Twentieth Party Congress probably cast a much longer shadow over domestic policies than foreign policies. Domestic policymaking and implementation are much more decentralized and open than foreign policy, providing politicians and bureaucrats with more opportunities to contrast their policies with those of peers before major personnel decisions. That diffusion of authority for local policy decisions means that a provincial party secretary can flaunt their zealous enforcement of zero-COVID protocols and economic officials can debate the remit of monetary versus fiscal institutions in ways that rival PLA service chiefs and theater commanders cannot.

The fundamental point is that the effect of political events on policy is contextual. The current configuration of power has placed strategic foreign-policy decisions in the hands of a calculating leader who is largely insulated from domestic pressure. So long as this dynamic persists, international policymakers seeking to anticipate Beijing’s moves should focus on Xi’s strategic calculus rather than the increasingly stage-managed rituals on his calendar.

Mark Parker Young is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and a principal analyst at Mandiant.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

Further reading

Thu, Nov 10, 2022

Will Xi take a new economic direction? China has trillions at stake.

New Atlanticist By Niels Graham

Without reform, China's economy could be five trillion dollars smaller than projected by the end of the decade—with ramifications for global growth.

Tue, Oct 18, 2022

An allied strategy for China after the 20th Party Congress

Issue Brief By

Chinese president Xi Jinping secured a third term in power as general secretary, and China is likely to continue along a more assertive course in global affairs. The United States and its allies need an updated strategy to navigate this period of relations with China.

Mon, Oct 17, 2022

Experts react: Xi solidifies his power at China’s Communist Party Congress. What should the world take away?

New Atlanticist By

We asked our China watchers to explain how the world should read Xi Jinping's approach to the economy, Taiwan, and more.

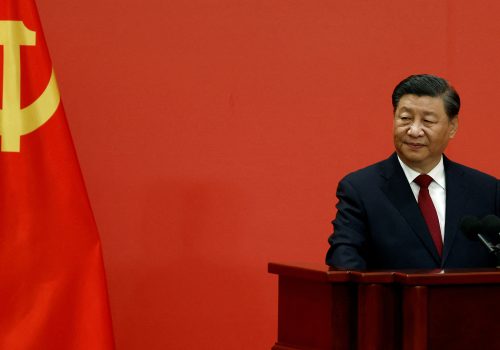

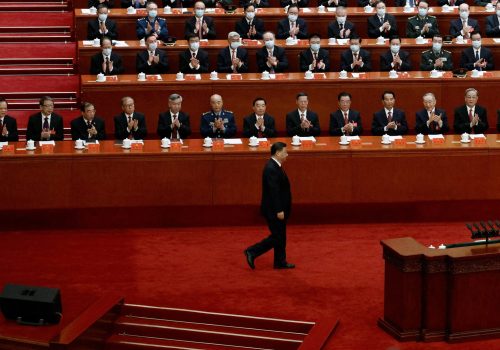

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping (standing) prepares to deliver a speech during the first day of the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party on Oct. 16, 2022, at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Photo via Reuters (Kyodo).