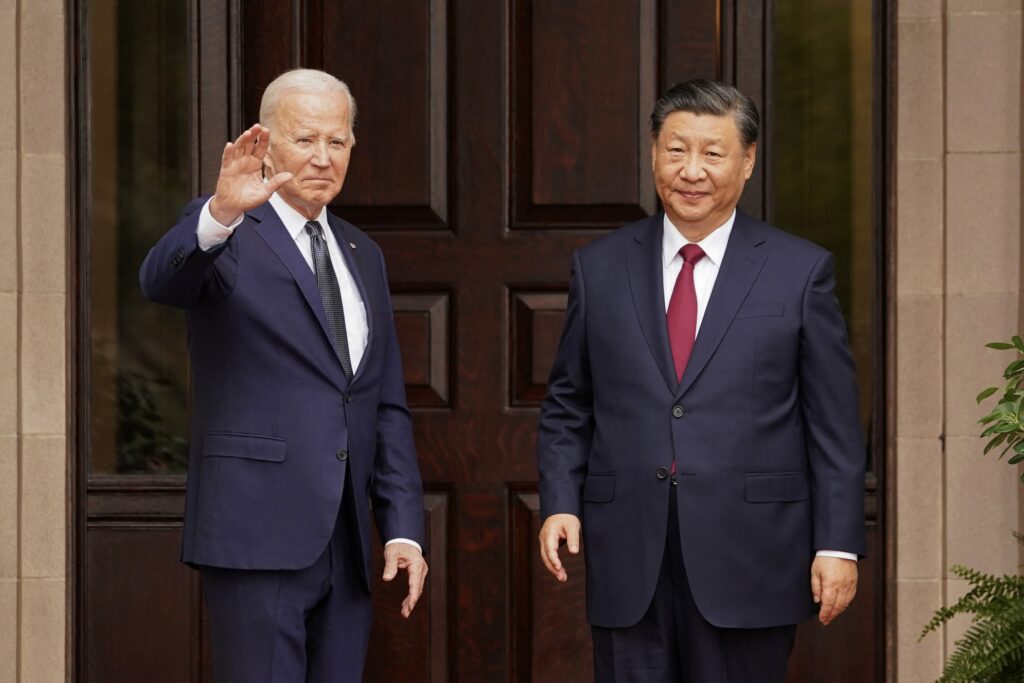

This week, US President Joe Biden will meet Chinese leader Xi Jinping in Lima, Peru, for the 2024 Leaders’ Summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). APEC is a twenty-one-member forum representing roughly 60 percent of global gross domestic product, and Biden’s trip to Peru for it constitutes the first stop in the president’s farewell tour and only his second trip to Latin America during his four years in office. While the summit’s agenda will focus on the host government’s priorities of deepening the bloc’s trade and investment ties, the simultaneous presence of the two most powerful world leaders in Latin America will command the attention of international audiences.

Biden’s visit to Peru, which will be followed by a trip to Brazil to attend the Group of Twenty (G20) Leaders’ Summit, is a final opportunity for his administration to diplomatically engage with governments in the Latin America region. Historically, the United States has featured as a premier trade and investment partner in Latin America, and Washington has wielded significant political influence. But recently and increasingly, Chinese political and economic ties have deepened in the region.

Chinese economic and political influence in Latin America has raised concerns in the US government. Last year, General Laura Richardson, the then commander of US Southern Command, warned that China “is on the 20-yard-line . . . to our homeland.” As such, the trip presents a welcome opportunity for the Biden administration to engage multilaterally with countries in the region and leave a parting message that the United States remains a partner and alternative to China. However, at the tail end of four years marked by geopolitical conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, which steered his administration’s foreign policy focus away from Latin America, Biden will arrive in Lima and Rio with little of substance to offer.

In fact, Biden’s presence in Peru will be eclipsed by what Xi will come to inaugurate on the sidelines of his visit: a massive deep-water port in the Peruvian coastal town of Chancay that is set to redefine trade between China and Latin America. At a cost of $3.5 billion, state-owned China Ocean Shipping Company Limited (COSCO) developed one of China’s most high-profile and controversial infrastructure projects. And after a five-year construction, it is ready to be inaugurated by Xi.

For Peru, the port will offer material benefits. Many Peruvians are hopeful that the megaport will elevate Peru into a key hub for global supply chains, particularly for exports from Latin America to Asia. Observers have also posited that the port could help diversify Peru’s economy, increase trade volumes between Peru and China, and attract further Chinese investment in Peru. Its construction has provided a boost to the local economy, generating roughly 7,500 jobs. Once the port is operational, many residents, who for decades have aimed to develop their skills through education, hope to become trained port workers with specialized skills in computer systems and cargo logistics. These aspirations speak directly to a priority for this year’s APEC summit: promoting the transition to the formal and global economy.

For all the opportunities it presents, the port has also faced significant criticism from international observers. In June, the Peruvian government amended Peruvian law to give COSCO unprecedented control over the port. US observers have justifiably raised alarms over the possibility of COSCO’s exclusive operational rights enabling the Chinese navy and intelligence services to use the port to spy on US naval and commercial ships. Chinese officials could also potentially use port equipment to steal proprietary commercial data.

Chancay is the latest development in a worrying pattern of Chinese state-owned companies, which are beholden to the political interests of their government, building and operating ports in strategic waterways across the world, from the Aegean Sea to the Panama Canal. If a conflict were to break out in, for example, Taiwan or the South China Sea, this global network of thirty-eight COSCO-operated ports could pose a serious logistical challenge for foreign militaries looking to move ships or supplies to the Indo-Pacific.

Through the port inauguration ceremony on the sidelines of this year’s APEC summit, Xi is attempting to send a clear message to current and prospective Belt and Road Initiative members: Both China and the United States will talk with you about inclusive growth and sustainable development, but only we will deliver the real thing.

What is the United States’ response to this? The Biden administration’s main proposal to deepen economic engagement with the region and counter Chinese economic influence in the hemisphere has been the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity (APEP), which aims to catalyze private sector investment to the Americas and deepen trade relations with its eleven founding members. APEP, however, has yet to yield material benefits that rival those of Chinese investment. Other investment projects, such as the US Development Finance Corporation’s (DFC’s) $150 million loan to finance the expansion and modernization of a port in Ecuador, or the DFC’s plan to partner with the US Agency for International Development and Taiwan to finance projects in the region, will take time to materialize into tangible trade and investment benefits that can be trumpeted as alternatives to China’s.

Beyond Chancay, Xi is expected to leave a trail of new economic cooperation agreements behind him as he travels to Lima this week and the G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro next week. The United States, meanwhile, is not expected to keep up. China is successfully pairing its economic diplomacy with action, and the United States should be concerned. The incoming Trump administration should recognize that advancing US interests calls for deeper economic engagement in Latin America. Any hesitation or inaction would inevitably allow Beijing to expand its influence in the region. If the United States leaves a leadership void, China stands ready to fill it, seizing the chance to frame the United States as retreating from its global responsibilities.

At the same time, the United States should recognize the difficulty of competing with China dollar for dollar and consider other ways to help recipient countries guard against the risks of Chinese investments. For example, the United States is well-poised to support host country efforts to screen investments and Chinese corporate entities, create effective oversight mechanisms, and bolster port cybersecurity.

After this year’s APEC summit and the inauguration of the Port of Chancay on its sidelines, Latin American countries may have an increased desire for diplomacy backed by tangible economic results. US policymakers should be prepared to deliver.

Martin Cassinelli is a program assistant in the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center at the Atlantic Council.

Caroline Costello is a program assistant in the Global China Hub at the Atlantic Council.

Further reading

Wed, Oct 23, 2024

China’s support for Maduro should be a warning to democracies in Latin America

New Atlanticist By Caroline Costello

China’s backing of Nicolás Maduro over the will of the Venezuelan people severely undermines Beijing’s claim to noninterference in Latin America.

Mon, Feb 26, 2024

Redefining US strategy with Latin America and the Caribbean for a new era

Report By Jason Marczak, María Fernanda Bozmoski, Matthew Kroenig

The strategic interest of the United States and the countries of Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) lies in strengthening their western hemisphere partnership. However, the perception of waning US interest and the rise of external influences necessitate the rejuvenation of and renewed focus on this partnership.

Tue, Jul 2, 2024

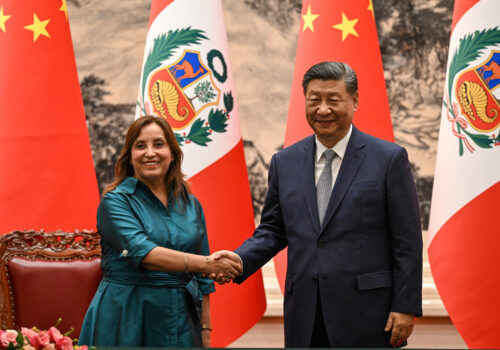

What the Peruvian president’s state visit to China means for US economic diplomacy

New Atlanticist By Martin Cassinelli

Peruvian President Dina Boluarte recently traveled to Beijing to meet with Chinese leader Xi Jinping. Washington should take note of the growing Peru-China relationship.

Image: US President Joe Biden waves as he welcomes Chinese President Xi Jinping at Filoli estate on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit, in Woodside, California, U.S., November 15, 2023. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque