Last March, the Biden administration released its interim National Security Strategic Guidance.

Aside from a veritable handful of national security scholars beyond the administration—and likely many more in China and Russia—this document probably sank without a trace before it was even launched. In fairness, the congressionally mandated National Security and National Defense Strategy reviews, which will codify US President Joe Biden’s policies and priorities, will be released in early 2022.

But the interim guidance no doubt will be repeated, possibly word-for-word, in these documents.

That alone should raise some profound questions. First, the interim guidance is part-aspirational, part-rhetoric to honor campaign promises, as well as part-ideological to set up what may be an unfortunate collision with China and Russia. The guidance does not offer specific actions or prioritize basic aims and objectives. But it does present what may be profound departures from the prior administration.

The president’s introduction makes the aspirational and ideological thrusts very apparent: “I firmly believe that democracy holds the key to freedom, prosperity, peace and dignity. We must now demonstrate—with a clarity that dispels any doubt—that democracy can still deliver for our people and for people around the world.”

And the president argues that the way to accomplish this is to: “build back better our economic foundations; reclaim our place in international institutions; lift up our values at home and speak out to defend them around the world; modernize our military capabilities, while leading first with diplomacy; and revitalize America’s unmatched network of alliances and partnerships.”

Clearly, this is fairly standard and unexceptional rhetoric. The critical questions include how these goals will be translated into action; with what priorities, resources and timetables; and most importantly, do these respond to the geostrategic, economic, social, environmental, and pandemic-related challenges and crises the nation faces? These are unstated and thus assumed to be answered in due course.

To underscore the competition and struggle with authoritarianism as an alternative political model, the guidance concludes that to prevail, we must demonstrate that democracies can still deliver for our people. It will not happen by accident; we have to defend our democracy, strengthen it, and renew it. No doubt, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea are listening.

Regarding national defense, we will ensure our armed forces are equipped to deter our adversaries, defend our people, interests and allies, and defeat any threats that emerge. But the use of military force should be a last resort, not the first. And, like former President Donald Trump’s National Defense Strategy—which directed the US military to compete, deter, and, if war comes, defeat a range of adversaries headed by China as the “pacing threat” and Russia—those objectives remain undefined and how each is to be achieved unstated.

Trump’s strategy was based on “America first,” a withdrawal from multilateral activities, and tariff wars to punish or coerce other states into dealing “more equitably” with the United States. The Biden guidance rejects international retraction (despite the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan) in favor of far greater collective action to take on issues such as climate change, COVID-19, and social and economic inequality—all noble intentions.

But can these aspirations be met? And will the focus on democracies as the means to solve international ills work—given that many are failing to provide for citizens’ needs? To some, this notion seems to reflect former President John F. Kennedy’s promise to “pay any price, bear any burden” to protect liberty, which led to the Vietnam debacle.

History may not be repeating, but as Mark Twain observed, “it often rhymes.”

If the forthcoming security and defense reviews merely elaborate on this guidance, will the United States and its friends and partners be any safer or more secure? While we await that answer, I would propose this as an integrating theme for the administration’s guidance:

During the Cold War, preventing thermonuclear war and the evisceration of much of humanity was expressed in the shorthand of MAD—mutually assured destruction. As long as both sides could destroy one another, nuclear deterrence would be maintained. And it was.

Today, a new version of MAD should stand for massive attacks of disruption, whether from nature—such as COVID-19 or climate change—or from man, in the form of cyber threats, terrorism, and other sources. The aim must be to contain, prevent, and defend against MAD, which includes the disruptive strategies of China and Russia.

Around that theme, specific actions can follow. But for now, a guess: The forthcoming reviews will suffer from the same shortcomings as the guidance.

A version of this article previously appeared on UPI.

Harlan Ullman is an Atlantic Council senior advisor and UPI’s Arnaud deBorchgrave Distinguished Columnist. His latest book, due out soon, is The Fifth Horseman and the New MAD: How Massive Attacks of Disruption Became the Looming Danger to a Divided Nature and the World at Large.

Further reading

Fri, Oct 22, 2021

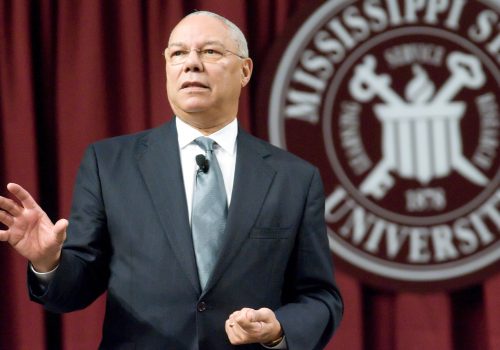

Colin Powell’s glorious American journey

New Atlanticist By Harlan Ullman

As a gentleman, Powell treated all people with great respect—no matter their rank or status.

Tue, Nov 16, 2021

FAST THINKING: Breaking down the Biden-Xi virtual summit

Fast Thinking By

While the three-and-a-half-hour talk reportedly covered trade, Taiwan, and human rights, it produced no major breakthroughs. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a big deal.

Wed, Dec 1, 2021

The world must carefully engage with Afghanistan. Here’s how.

New Atlanticist By Harris A. Samad

Ignoring Afghanistan would be a catastrophic mistake for the international community—as would be a rush to recognize the Taliban.

Image: President Joe Biden speaks at the White House in Washington, DC, on Aug. 31, 2021. Photo by Stefani Reynolds/Pool/ABACAPRESS.COM