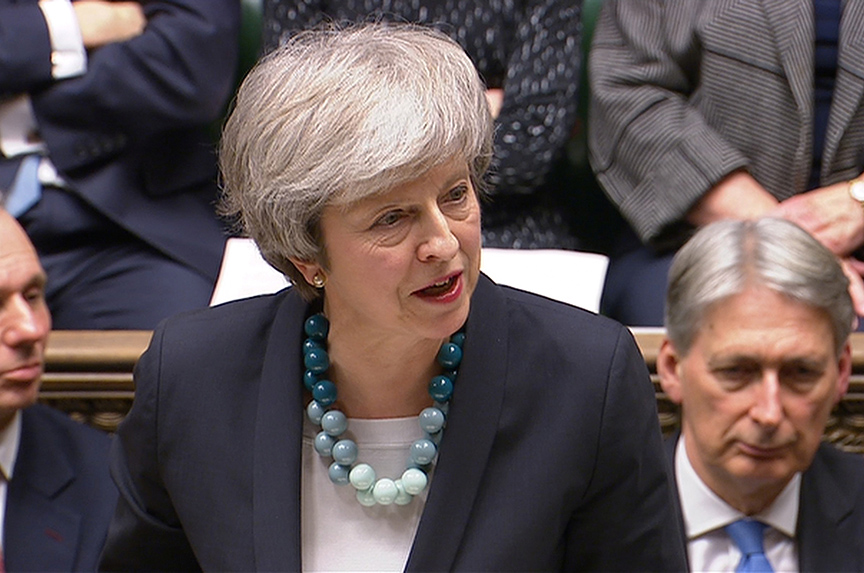

British Prime Minister Theresa May on December 10 decided not to call a long-expected vote on her plan to take the United Kingdom out of the European Union (EU). The underlying reason is continued controversy over the so-called Irish backstop—a fall-back plan that would maintain an open border on the island of Ireland if the UK leaves the EU without securing a deal. But while there is a mountain of controversy over the backstop mechanism itself, and whether it might lock the UK, against its will, into a near permanent customs union with the EU, there is virtually no discussion of the underlying political—and security—rationale for the backstop.

The rationale concerns security conditions in Northern Ireland and the need to ensure that the UK’s planned departure from the EU does not result in anything that could lead to a resumption of the vicious strife that dominated life in Northern Ireland for thirty years and caused more than 3,000 violent deaths.

Even on December 10, as she caused a parliamentary furore by announcing during the middle of a five-day debate on her Brexit plan that there would be no vote at the end of it, the prime minister devoted just twenty words in her prepared statement to the true reason why the backstop remains essential.

There were, she said “inescapable facts.” And the first fact she cited was that “the hard-won peace that has been built over the last two decades (in Northern Ireland) has been built around a seamless border.”

May was alluding to one of the key elements in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended the conflict: the fact that the UK and the Irish Republic were members of the EU and were bound together in both a customs union and a single market. This was crucial for Republican forces who believed—and still believe—that Northern Ireland should be united with the Irish Republic instead of being part of the UK.

What makes the Brexit question so problematic and dangerous in an Irish context is that the Good Friday Agreement, to which both the British and Irish governments were signatories, has the status of an international treaty. This means any agreement for the UK to leave the EU, which would normally result in the resurrection of customs barriers between the UK and its former European partners, has to ensure that there is no return to a hard border along the 310-mile line that separates north from south.

Responding to comments from a plethora of critics in the wake of her statement, May told Parliament on December 10 that the British government “retains its commitment to the Belfast Good Friday Agreement and the commitments the government made within that agreement.”

The border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic is a highly delicate political issue. Farms and businesses have premises that span both sides of the line while much larger enterprises depend on easy cross-border connections for delivery of goods and services. A generation ago, the line was overlooked by grim watchtowers and sangars erected by the British army to police the rough terrain of the inter-Irish border during its bitter war with militants of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), a body banned on both sides of the border.

While there are, no doubt, a few die-hard militants who still believe armed conflict is the way to achieve a united Ireland, the Irish government in Dublin and the British government in London are united in their determination to ensure there should be no return to the violence of “The Troubles.”

At an EU summit meeting in Brussels in October, held largely to discuss the Irish border issue, Irish Taoiseach (prime minister) Leo Varadkar warned of the dangers of a return to violence if Brexit resulted in a hard border in Ireland. At dinner, Varadkar produced a photograph showing the devastation caused by an IRA van bomb at a British army post on the border at Newry in 1992. He explained: “I just wanted to make sure that there was no sense in the room that in any way anybody in Ireland or in the Irish government was exaggerating the real risk of a return to violence in Ireland.”

There are alternatives to a hard border, but these either involve complex digital and technical solutions or, more simply, they involve checks on the sea routes between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, the so-called Irish Sea border solution. The British government initially favored a technological solution, including digital monitoring and physical spot checks at distribution points well away from the actual Irish border, but the digital side of all this remains essentially untested.

As for the Irish Sea border option, this is fiercely rejected by Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), with which May’s minority Conservative administration has an increasingly strained “confidence-and-supply” agreement in order to ensure an overall majority in the House of Commons at Westminster.

The DUP’s ten members of Parliament at Westminster seem to hate the backstop more than anything. But neither the DUP nor the UK government really wants to discuss openly the question of whether a Brexit agreement might result in the resumption of major violence in Northern Ireland.

And, at present, politics in Northern Ireland is already more strained than at any time since the Good Friday Agreement was signed twenty years ago. A dispute over financial mismanagement led Sinn Fein, the Republican partner in the power-sharing arrangements, to walk out of the devolved Northern Ireland government in January 2017. With the British government unable to secure a reconciliation between Sinn Fein and the DUP, and reluctant to impose direct rule, this has led to a curious situation in which day-to-day government is handled by civil servants while policy matters are set aside and remain unresolved.

There is a worrisome imbalance in all this. Sinn Fein, generally considered the political arm of the IRA, became a partner in government in Northern Ireland as a result of the Good Friday Agreement. But its antipathy to the DUP, and in particular to DUP leader Arlene Foster, means it is not prepared to do business with its former government partner.

At the same time the DUP, which was the only major party in Northern Ireland to reject the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, is now playing a key role in determining British attitudes to the backstop, with all that that the backstop and a revived hard border might entail in terms of the return of violence to Northern Ireland.

The outlook is not good. Just before May addressed Parliament, Foster tweeted: “Just finished a call with the Prime Minister. My message was clear. The backstop must go.”

John M. Roberts is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center and Global Energy Center.

Image: British Prime Minister Theresa May on December 10 called off a December 11 vote on her Brexit deal. (Parliament TV handout via Reuters)