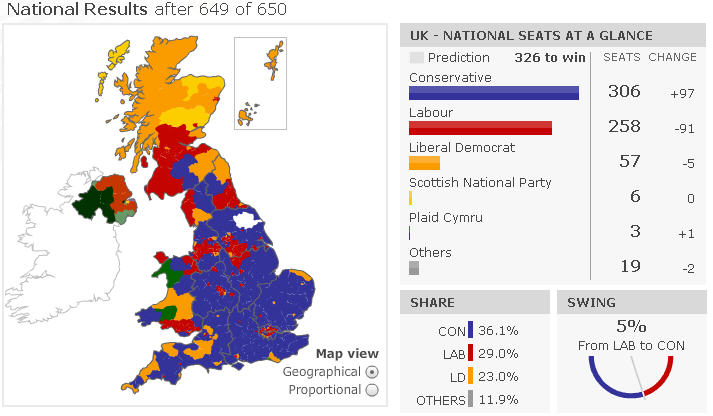

As expected, yesterday’s UK elections resulted in a hung parliament, with the Tories falling short of an outright majority needed to form a government on their own. While Nick Clegg and the Liberal Democrats wound up in distant third, they’re now in the driver’s seat.

Conservative leader David Cameron has reached out to Clegg to form a coalition. While seemingly a pairing of strange bedfellows given the closer ideological proximity between the LibDems and Labour, the election was rather obviously a repudiation of Gordon Brown and a signal that the voters have grown tired of Labour after thirteen years. So, it’s natural that the two "change" parties would try to work together. (Credit where due: The Spectator‘s Alex Massie was one of the few calling this early on.)

WSJ’s Iain Martin notes that, after the short-lived "Cleggmania," the actual results are a shocking rebuke:

Nick Clegg has just been absolutely humiliated. (This inconvenient fact is being mostly skimmed over by the BBC today for some reason). Clegg’s new politics is a smoking ruin. Cleggmania is destined to be an amusing trivia question in years to come. He has actually lost seats. His vote share has barely gone up. He is in no position to dictate terms to anyone, and I strongly suspect he’s bright enough to know it.

The Tory leader’s smartest course of action on electoral reform would be to offer not a sausage, nothing, hee-haw.

But that’s rather short-sighted. If Clegg demands too much then, sure, Cameron would be a fool to concede it. But some sop on policy or ministerial seats is generally the price of coalition-building and I would be shocked if Cameron balks at paying. Indeed, Cameron’s public comments have been quite conciliatory:

"I want to make a big, open and comprehensive offer to the Liberal Democrats. I want us to work together in tackling our country’s big and urgent problems – the debt crisis, our deep social problems and our broken political system," he said.

While there were policy disagreements between the Tories and Lib Dems – including on the European Union and defence – there were also "many areas of common ground".

At the same time, Cameron is not offering electoral reform, despite Clegg’s party winning a far smaller share of seats than they did of the popular vote.

Expat Scotsman Steve Hynd notes that Brown actually did quite well, given that most of us thought his government was going to fall a year back and that a Tory landslide was inevitable.

But then came some Labour bounceback as Brown proved he was always a better Chancellor than PM and, of course, "Cleggmania". The Liberal Democrat leader proved more charismatic than Broon and less toffee-nosed smarmy than Cameron in the debates, fuelling speculation among many that the Lib-Dems might finally break through and be more than the "other party".

That didn’t happen. The LibDem vote was up less than 1%. And while there was an overall national swing to the Tories of 4%, that swing was an average rather than a trend.

[…]

So, for what it’s worth, here’s what I think happened. With the benefit of Hynd-sight (sorry), the 2010 election was always going to be about two polarizing currents in British politics: the legacy of Blair/Brown vs the legacy of Thatcher/Major. Both ruled too long and both screwed over large sections of the populace more than they had any right to. But with tough economic times everywhere, not just in the UK, people went for what they knew, what was psychologically "safe". England outside the very big cities has always been more conservative and right-leaning than not and they voted for the Tories. In Scotland and the inner cities, they returned to the bosom of the party they’ve always backed in tough times and voted Labour. The Lib-Dems couldn’t overcome that decades-long inertia of voting habits.

For his part, Brown is not conceding defeat, noting that he is still prime minister and that, should Cameron and Clegg fail to achieve an accord, he would make an offer on his own. Complicating matters is that, if the projected allocation of seats holds, Labour’s 261 seats and Lib Dems 55 would still fall short of the 326 needed to form a majority, meaning that they’d need to get another 10 seats from somewhere. Indeed, since the fourth place DUP only has 8 seats, a coalition would actually need to include at least four parties.

The Times‘ Peter Riddell assures us that, whatever happens in the short term, the medium term holds another election in store.

Any government formed in the next few days will not be able to command a stable or overall majority in the Commons. So the new Parliament is unlikely to last more than a year or so. A second general election is probable either later this year or in the spring of 2011.

Everything else is uncertain.

The only way out, a Conservative/Lib Dem coalition, looks highly unlikely because of Tory opposition to electoral reform.

As politician after politician said overnight, the public has spoken, but it is not clear what they have said. The Tories were certainly the main winners of the night, gaining more seats than Baroness Thatcher did in 1979. Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats were the losers: the former by less than expected and the latter in an unexpected and unpredicted reverse.

Whether a true coalition government is formed or not, however, Riddell thinks Cameron will almost certainly emerge as premier. For now, at least.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council. Graphics: BBC.

Image: uk-election-2010-bbc.jpg