No one knows just what will be the outcome of Britain’s fraught negotiations to leave the European Union—and that means no one knows whether the United Kingdom will remain united after Brexit.

Several ministers in British Prime Minister Theresa May’s Cabinet, speaking anonymously, have told the BBC they believe a “no deal” Brexit could lead to a vote on Irish unification. Sinn Fein, the Republican party which wants to see the British province of Northern Ireland unite with the independent Republic of Ireland, has already called for a vote on Irish unity after Brexit.

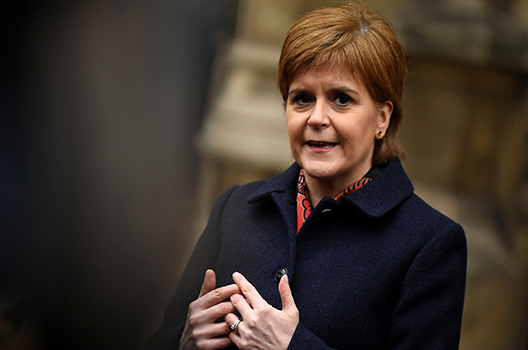

Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has stressed that she remains committed to holding a second referendum on Scottish independence but that she is waiting for clarity on Brexit before committing herself to the timing of such a vote. And Sturgeon and the first minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, issued a joint statement on February 7 in which they pleaded with May to rule out any “no deal” Brexit and called on her to ask the European Union for an immediate extension from the Article 50 deadline of March 29. The two first ministers declared: “All the evidence we have seen to date suggests that the UK is simply not prepared for a ‘no deal’ Brexit in less than two months’ time.”

May is continuing to insist that Britain will leave the EU on schedule on March 29. However, right now, there is no clear indication as to whether Britain will leave on that date on terms that have been mutually agreed with the EU; or whether it will crash out of the EU without a deal; or whether, by then, Britain and the EU will have simply agreed to delay everything to allow more time for further negotiations or—a remote possibility at present—for a new referendum that might possibly offer Britain an opportunity to remain an EU member.

Northern Ireland

The immediate focus is on Northern Ireland. In the Brexit referendum of June 2016, voters in Northern Ireland supported remaining in the EU by 55.8 percent to 44.2 percent. The problem Northern Ireland faces with Brexit is that it risks ending one of the key underpinnings of the Good Friday Agreement which ended thirty years of largely sectarian violence, namely the fact that because both Britain and the Republic of Ireland were grouped in a single market and customs area within the EU this meant that the old border between the two had become virtually invisible. Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland might remain separate political entities, but there were far less physical and psychological barriers separating communities.

It is easier to gauge the chances that a poll on Irish unity will be held in the north than to predict the outcome. The Good Friday Agreement provides for the British government to hold a referendum on the subject, if there are grounds for believing that that would be the wish of a majority of the population. The province’s demographics are changing steadily, with generally pro-Irish nationalist Catholics approaching numerical equality with generally pro-UK unionist Protestants. (The last census in 2011 identified 48 percent of the Northern Ireland’s 1.8 million people as Protestant and 45 percent as Catholic). Indeed, there are already more schoolchildren and students from Catholic backgrounds than there are from Protestant backgrounds. But there is no guarantee that voting in any unity poll would entirely follow sectarian lines.

Scotland

In a speech at Georgetown University on February 4, Sturgeon recalled that Scotland voted in 2016 to remain in the EU by 62 percent to 38 percent, “so, as things stand right now, on March 29… Scotland faces the prospect of leaving the European Union against our democratically expressed will.”

The prospect of moving to a second referendum on Scottish independence was only one of three major points Sturgeon sought to make to highlight her opposition to Brexit. The first point was her government’s firm view that immigration, viewed by many as the leading reason why Britain voted as a whole to quit the EU, was in fact very positive for Scotland. The second addressed the fact that much of the Leave vote in 2016 came from less well-off areas in Britain, which had failed to share in the wealth generated over the last thirty or forty years. Brexit, the first minister said, “is the wrong response to inequality—because it’s likely to make people’s living standards worse rather than better.”

Sturgeon faces a much harder task in both securing an independence referendum in Scotland and then winning it, than do Republicans favoring Irish unity. That is because the holding of such any vote on Scottish independence must be agreed by both the Scottish and British governments, and May’s government is vehemently opposed to another independence vote for Scotland, since it is only five years since the first referendum on independence was defeated 55.3 percent to 44.7 percent.

If Britain crashes out of the EU without a deal it will be largely because of widespread opposition to the EU among Conservative members of Parliament representing English constituencies, coupled with a cluster of opposition Labour MPs representative English seats in areas that have suffered from de-industrialization. This makes Brexit a particularly English affair. Indeed, it look increasingly as if the idea of a “no deal” Brexit is one that is largely confined to England, the largest element in Britain with some 55.8 million of Britain’s 66 million people, together with the embattled Protestant community in Northern Ireland.

Even though Wales also voted in 2016 to leave, its government favors continued EU membership and there are opinion polls showing that a majority in Wales now feel it was a mistake to vote to leave the EU.

Britain’s old nationalities are reasserting themselves. In 2014, Scots voted to remain within Britain, of which they have been a part since the England and Scotland came together in 1707 to form the United Kingdom, for a variety of reasons, including continue membership of the EU.

The economics for an independent Scotland, particularly in its early years, do not look good. But neither do the economics of Scotland if it were to find itself in a Britain severed from the EU without a properly negotiated exit. In her joint statement with Drakeford, Sturgeon said “the Confederation of British industry has estimated a No Deal Brexit could cost the Scottish economy £14 billion ($18 billion) a year by 2034.”

Britain’s vote to leave the EU was, in large part, the result of appeals to atavistic English nationalist impulses. Who is to say that the same impulses won’t prompt Scotland to leave the UK?

John M. Roberts is a UK-based senior fellow at Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center and Global Energy Center.

Image: Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon speaks to the media after Parliament rejected Prime Minister Theresa May's Brexit deal, in London, Britain, January 16, 2019. (REUTERS/Clodagh Kilcoyne)