Answer lies in Pakistan’s willingness to end support for militants, says Atlantic Council’s James B. Cunningham

Representatives from Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, and the United States are meeting in Islamabad this week to draw up a roadmap for peace talks with the Taliban.

James B. Cunningham, a former US Ambassador to Afghanistan and current Khalilzad Chair on Afghanistan and Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, discussed the prospects of peace in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from our interview.

Q: Peace talks fell apart last summer following news that Taliban leader Mullah Omar had been dead for more than two years. What has kept the talks from getting back on track?

Cunningham: The revelation that Omar had died two years before had several negative implications. The Afghans thought that they were in the process of establishing a discussion with Omar. News that the Taliban leader had been dead for two years brought into focus the mistrust that exists towards Pakistan because obviously the Pakistani intelligence services would have known that Omar was deceased. It also caused a split in the Taliban leadership with the naming of Omar’s successor [Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour] who was not accepted by all members of the Taliban. So there had to be time for all of this to settle and be digested.

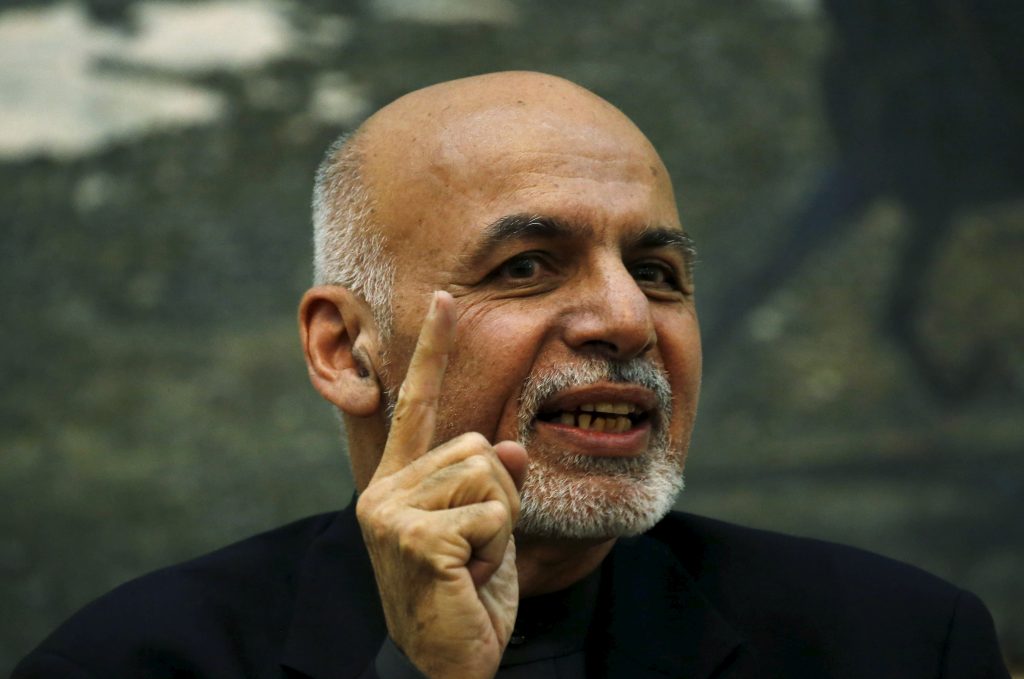

Afghanistan’s friends—the United States and others—were of the view that when possible the effort should be resumed notwithstanding all the problems that were created. That required several things to take place to reopen channels of communication and a decision by [Afghan] President [Ashraf] Ghani that he wanted to resume the effort to bring the Taliban to the table through Pakistan as well as other efforts that are underway to engage the Taliban.

Ghani’s decision to go to Islamabad for the Heart of Asia meeting and to meet with [Pakistani] Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to discuss how they might resume this process and what Pakistan’s role, including the crucial role of its military and intelligence services, might be, led to the conclusion that it was worth trying to resume this effort. The Prime Minister made clear that Pakistan would respect Afghanistan’s sovereignty, which was important. It was also clear that the United States and China were both willing to be sponsors of this process. [Pakistani Army Chief] Gen. Raheel Sharif’s visit to Kabul right after Christmas solidified the process that was coming together. All this led to the meeting taking place in Islamabad.

Q: What are your expectations from the meeting in Islamabad?

Cunningham: Expectations have to be modest. But I am hopeful that the discussions between the four parties will lead to a clear understanding on a way ahead that the Afghans and Pakistanis are willing to pursue.

Part of the new equation that didn’t exist last summer is clarity, finally, that the United States is going to remain militarily engaged in Afghanistan in a significant way for some time. That is a very important new factor in the equation.

Another is that there is a growing sense among Afghanistan’s partners that in order for a peace discussion to be a real phenomenon Pakistan needs to obstruct the ability of the Taliban to live, plan, and organize in Pakistan.

This new combination of factors will, I hope, work to change the dynamic that has existed up until very recently. There is, clearly, disagreement within the Taliban about how to proceed. As we argued in the report released by the Atlantic Council in October, one needs to change the strategic calculation of the Taliban and demonstrate that the goals that they have are not achievable through violence and terrorism. That seems to me to be one of the principal strategic objectives going forward.

Q: The Taliban today is not a cohesive group under a unified leadership. To what extent is this going to complicate efforts to restart peace talks?

Cunningham: There is a school of thought that believes that a united Taliban leadership is necessary to negotiate. I have never really thought that that is the case. I have always thought that the United States should support Afghanistan negotiating with any Taliban who are willing to reconcile and come off the field.

If there is a possibility of beginning a discussion with the Taliban who will represent which groups of people? The way things stand right now, it seems that there likely will not be a unified approach, but it would certainly be a good thing if a genuine discussion about ending the violence in the first place and then creating lasting peace could begin with a leadership that represents as much of the Taliban as possible.

The goal for everybody, I hope, will be to bring the violence to as much of a halt as possible and then turn to a political process for dealing with the issues that need to be resolved. That could certainly take place even if there are those who reject the process.

Taliban leader Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour. (Reuters)

Q: Mansour, Omar’s right-hand man, was leading the Taliban at the time when peace talks were underway and before Omar’s death was made public. Is Mansour more favorably inclined towards peace negotiations?

Cunningham: It is hard to speculate about his views. He was clearly representing the Taliban in the absence of Omar. He was at the helm when the process began last summer. I would hasten to note that sitting down and talking is not the same as actually negotiating and trying to find a solution. That’s where the role of Pakistan will be important.

The Taliban will be encouraged to negotiate seriously by the knowledge that their support structure is not going to remain as it has been in the past, and by the knowledge that the United States and our partners are going to keep assisting the Afghan security forces.

It is too early to say how that will develop in the coming months, but at least in the past one assumes that Mansour was willing to begin at least sitting at the table with the Afghans. That is the first step.

Q: Has the emergence of ISIS in Afghanistan complicated efforts to make peace with the Taliban, which may now be reluctant to give up territory that could be seized by ISIS?

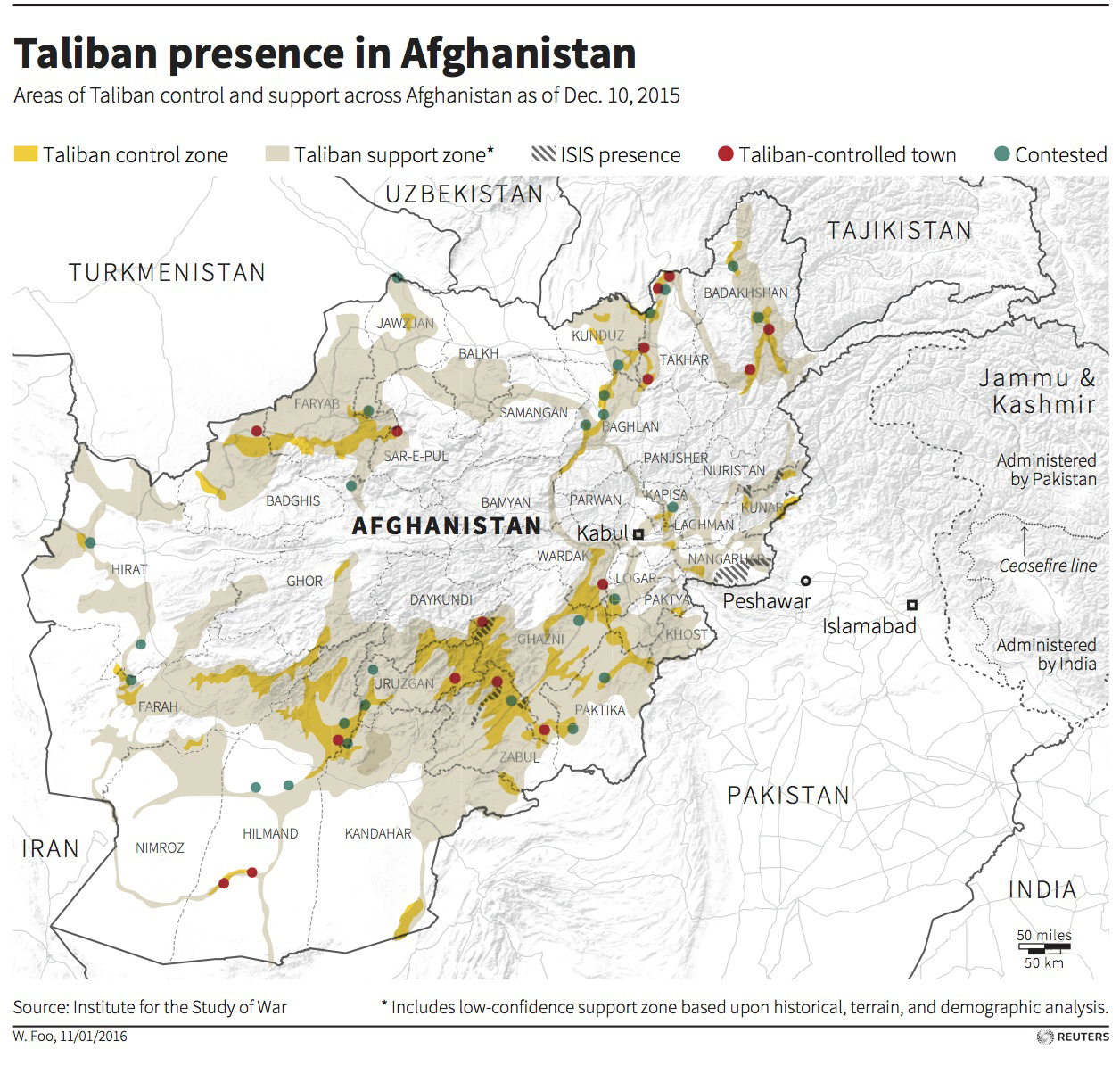

Cunningham: I don’t think that any Afghan is going to willingly cede territory to Daesh [another name for the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham]. Its presence in Afghanistan certainly does complicate things by bringing a vicious external actor into the scene. Daesh is not present in a dominant way, so far, but it is there.

It gives the wrong message to suggest that Daesh doesn’t matter because it is a rebranding of disaffected Taliban, which is what it seems to be along with some foreign fighters. But, as we have seen in Libya and probably will see elsewhere, these local groups, when they identify with the Daesh movement, if they establish themselves in occupied territory they then make the connection with [ISIS’] central leadership. That is the danger in Afghanistan.

Another reason for a certain amount of urgency and focus on trying to create a political process is that over time this phenomenon will replicate itself—not that Daesh will take over and reject the Taliban as the Taliban rejects Daesh now, but that it will establish itself nonetheless, which will make it a danger in that part of the world. The ideological home of Daesh is in what they call Khorasan, which is Afghanistan and northern Iran.

Q: The Taliban today controls more territory today than at any point since it was ousted from Kabul in the 2001 US-led invasion. In the past six months it has conducted high-profile operations in Kunduz and Kandahar. Is Mansour trying to assert his leadership and come to the negotiating table from a position of strength?

Cunningham: That is probably part of it, but it was also expected that 2015 was going to be a very difficult year because it was clear that with the end of the international mission and the US combat role in Afghanistan the Taliban would press very hard into the Afghan security forces.

Some observers believe that one of the Taliban’s aims was to establish a territorial sanctuary within Afghanistan from which they could operate, instead of operating from within Pakistan. That hasn’t happened. The Afghan forces, while they have taken a lot of losses, have fought and are learning lessons. The knowledge that the United States and our partners are going to be there and providing not just training and assistance, but also critical enabling support that the Afghans don’t have available, will provide more clarity about the security situation going forward as the Afghans learn and address the shortcomings that have been exposed in Kunduz and the fighting in Helmand.

As long as there is Afghan will to resist, which there is; international support to compensate for shortcomings, which we have now made clear will be there—and I hope that we will emphasize that message; and things that are already underway, such as building up the Afghan air force, come into being, it will become clear that the Afghan forces are becoming better and not worse and the Taliban will not be able to occupy significant amounts of territory.

It is undoubtedly true that the Taliban occupies more territory than in the past, but it is not crucial territory and when they have occupied territory often it has been taken back.

Q: President Ghani staked a lot of his political capital early in his presidency on an outreach to Pakistan. That didn’t pay off. Can it now? Are you seeing a different approach from Pakistan, especially its military, in light of Gen. Raheel Sharif’s visit to Kabul last month?

Cunningham: I haven’t seen a change in their approach yet except in the limited sense that they have resumed the dialogue at a very high level. I hope they realize how difficult this is politically for the Afghan government.

President Ghani is again expending political capital based on the premise that there is a positive way to move forward with Pakistan. That remains to be proven. The rhetoric has improved. The symbolism and the political gestures from [Pakistan’s] civilian government as well as the military have improved. But the proof will be in what actually happens.

Q: Is it important that groups like the Haqqani Network are part of a peace effort?

Cunningham: There are many people who have felt that the Haqqanis, because they are as much a criminal group as anything else, are not reconcilable, and that they have temporal and financial interests that they are trying to secure. They have, in the past, pledged allegiance to Mullah Omar. Now Siraj Haqqani, who is the operational head of the network, is a deputy of Mansour’s. The Haqqanis have always had representatives in the Taliban leadership, but this is a qualitative step up. What the implications of that will be at the end of the day remain to be seen.

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Afghan President Ashraf Ghani said at a news conference in Kabul, Afghanistan, on December 31, 2015, that international meetings to lay the groundwork for a possible resumption of peace talks with the Taliban had to seek an approach to the fractured insurgent movement that ensured a rejection of terrorism. (Reuters/Omar Sobhani)