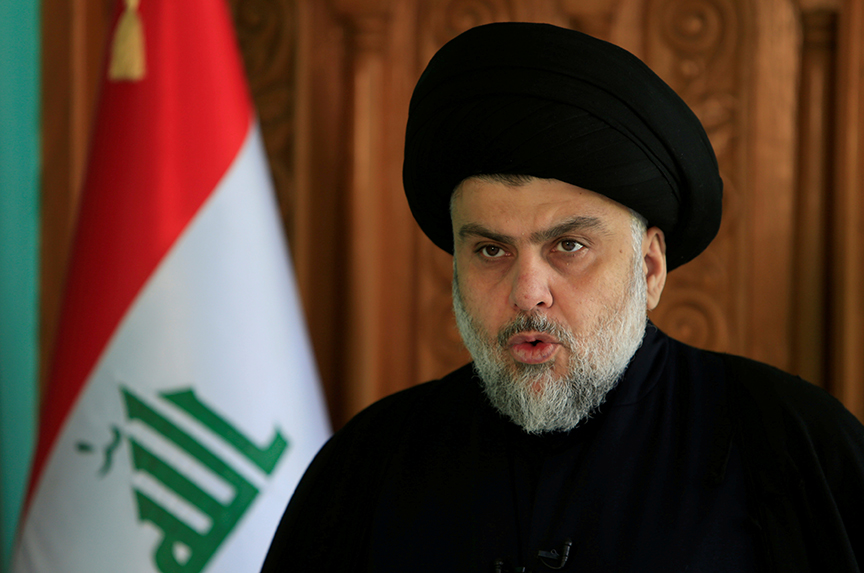

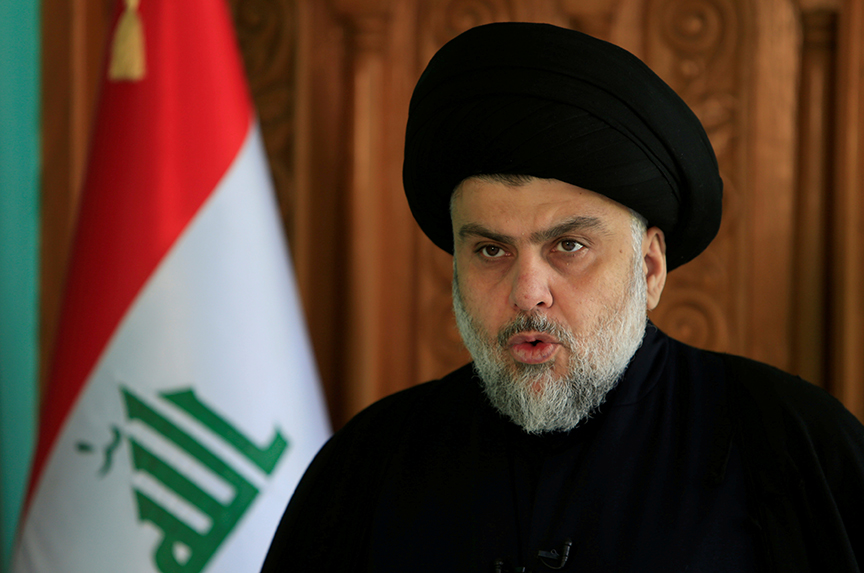

Amid the uncertainty that has followed the Iraqi parliamentary elections on May 12 one thing is clear: formerly anti-US Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr’s list is the top vote-getter.

Amid the uncertainty that has followed the Iraqi parliamentary elections on May 12 one thing is clear: formerly anti-US Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr’s list is the top vote-getter.

Sadr is trailed by Iran-backed Shia militia leader Hadi al-Amiri in second place and current Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi in third according to the unofficial results that are subject to change in the upcoming days.

Sadr, who formed the Mahdi Army in response to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, has since disbanded the group and transformed himself into a leading Shia politician.

In an interview with the New Atlanticist, Harith Hasan, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, discussed the opportunities and challenges presented by the elections.

For one, he said, if Sadr and Abadi join forces in a governing coalition it would give Iraq a centrist, reformist government that could be more resistant to the Iranian influence. This, among other factors, is reason enough for the United States to support such a coalition, he added.

“Sadr is not an easy partner for the Americans, but at the same time he is no longer the enemy,” said al-Qarawee.

“Now he is a Shia figure who is trying to contain the Iranian influence in Iraq. He is an Iraqi nationalist who has become more pragmatic than before,” he added.

Here are excerpts from our interview.

Q: What are the main takeaways from the Iraqi elections?

Hasan: The first is that [voter] turnout was lower than all the previous elections that have taken place in Iraq since 2003. A 45 percent turnout indicates growing disillusionment with the system.

There were demands to adopt a different electoral system that allows new parties and independents to compete, but the political elite did not respond to these demands. There was a feeling that the electoral process has been used to preserve the power of the established political groups. As a reaction, there were also calls for Iraqis to boycott the vote.

Another important takeaway was the fact that the electoral map was very fragmented. There was no grand coalition that could claim the support of a majority of Shias, Kurds, or Sunnis. The intra-communal competition was more intense than in previous elections. This could create the possibility of having groups from different ethnic and sectarian backgrounds allied together in one coalition, thereby overcoming the previous formula in which most of the alliances were based on communal solidarity—a grand Shia alliance, a grand Sunni alliance, and a grand Kurdish alliance, for example. However, this possibility remains limited and communal alliances are likely to be revived if cross-sectarian coalitions fail to materialize.

In the election, there was greater focus on governance issues than on identity politics. There was no strong emphasis on sectarian or ethnic mobilization, but a greater focus on the groups trying to build their own distinct brands.

It is important to note that in Iraq elections don’t simply tell you who is the winner and who is the loser. No party has the majority with this fragmented electoral map. There will be a longer process in forming the largest bloc in the parliament, which will have the mandate to form the government. Post-electoral negotiations and compromises will play a major role in the process of the formation of the next government.

Q: What are the next steps toward the formation of a government?

Hasan: It now depends on which parties manage to form an alliance that will have the largest number of seats in the parliament. According to the Iraqi federal court, the bloc that has the largest number of seats will be mandated to form the government. This could be the coalition that won the most seats or a new coalition emerging before the first session of parliament. It could take more than a month for the results to be certified by the federal court.

Meanwhile, the political parties, especially the major Shia parties, will try to gather the largest alliance. Here there are two possible scenarios. First is a scenario in which Sadr, whose coalition unofficially has the most seats, will try to ally with Abadi and form a new bloc based on their similar programs. They both criticized a government based on the apportionment of executive positions among political parties (a practice known in Iraq as muhassessa); they both prefer a government of independents and technocrats backed by a parliamentary majority. This would be a promising scenario because it would also imply an avoidance of alliances formed on basis of identity politics and perhaps a more effective mode of governance, which Iraq desperately needs to deal with its social and economic problems, as well the security challenge.

Second, if this attempt fails, Abadi’s party will push him to form an alliance with other groups that are closer to Iran and Iran will put pressure on its Shia allies to come together again. There could be an effort to exclude Sadr because he has been vocal against the revival of sectarian alliances and critical of foreign interventions. Such a dynamic will be a return to a very unpopular formula, which has in the past seen the formation of weak governments divided among different parties.

Q: What does Muqtada al-Sadr’s surprisingly strong performance in the election mean for Iraq?

Hasan: The low turnout helped Sadr gain more seats than expected. He has a more consolidated base than the other parties and a better grass-roots organization which helped mobilize his base during the voting.

Sadr has rebranded his group in the last few years. In 2015, when massive protests against the government erupted Sadr repositioned himself as an opponent of the established parties and the existing system of governance. He changed the nature of his movement, attracted secular supporters, and allied with the Communists.

Most other parties depend a lot on patronage. Sadr, in contrast, has been able to cultivate support by appealing to popular demands, often using a populist discourse that appealed to his base and the growing anti-establishment sentiments.

This is important because it shows that engaging in politics has helped change a major player from a radical opponent of the democratic process into an active actor within it, albeit with a peculiar style and discourse. It also gives hope to alienated Iraqis that it might be still possible to change the system from within.

Q: Sadr, a Shia cleric, formed a coalition with secular Sunnis and Communists. Can he serve as a unifying force in the country?

Hasan: Sadr is no longer perceived as a radical leader of militias involved in a brutal civil war, as was the case in 2006-2007. When it comes to sectarian and ethnic divisions, he seems to be less polarizing compared to some other politicians. There is now an agreement that he is someone that other political groups can deal with. The fact that he is very popular in his base provides him with the ability to make concessions to other groups and market these concessions.

Having said that, clearly Sadr will not dictate the whole process by himself. The margin by which he won the election is very, very small. He will have to enter into long and painful negotiations with other parties.

Q: As the leader of the Mahdi Army, Sadr’s forces fought US troops in Iraq. The Mahdi Army has long since disbanded. What does Sadr’s electoral performance mean for Iraq’s relationship with the United States?

Hasan: The United States will need to be very careful in its policies and how it reacts to the results. Obviously, there is a long-established suspicion of Sadr. He was perceived as an anti-American figure. He refused to deal with the Americans directly. Building on that, Sadr is not an easy partner for the Americans, but at the same time he is no longer the enemy.

Now he is a Shia figure who is trying to contain the Iranian influence in Iraq. He is an Iraqi nationalist who has become more pragmatic than before. This has created an opportunity for the moderate Shia forces—particularly Sadr and Abadi—to come together in one coalition that could secure the majority in the parliament.

This will be an important step forward to overcome sectarian divisions. A centrist, reformist government is something that the United States should support because its consequence would be strengthening an Iraqi nationalist approach in the government.

What the Americans should not do is revert to business-as-usual thinking because they don’t know Sadr very well. They might be tempted to think that it is safer to support the old formula of compromising among sectarian coalitions and reaching a tacit agreement with the Iranians about the next prime minister who would preside over a weak and ineffective government in which the United States and Iran share influence.

This election has created an opportunity to invest in a new dynamic in Iraq. The United States should not miss this opportunity.

Q: What are the implications of Sadr’s rise for Iraq’s relationship with Iran?

Hasan: While Sadr has more seats than the others, it is also very possible that he might be excluded from government if the other Shia parties come together. The Iranians are not without cards. They could try to mobilize their own allies who are not only Shia; they also have Kurdish allies such as the PUK [the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan].

Although he has tried to emphasize Iraqi nationalism and distance Iraq from Iranian—and American—influence, Sadr is also careful not to completely alienate the Iranians and make them feel that he is a threat to them. He has had to go through some pragmatic compromises with them.

If Sadr and Abadi come together in one coalition that will not be good news for the Iranian hardliners. It would mean that an Iraq-centric government will be formed, which, while keeping friendly relations with Iran, is not going to be a proxy for the Iranians. So, the Iranians will have some difficult choices to make about how they want to project their influence in Iraq. If they want to push against [a Sadr-Abadi government] or a more reformed style of governance, they might create more enemies in the long run inside Iraq.

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on twitter @AshishSen.

Harith Hasan is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. Follow him on Twitter @harith_hasan.

Image: Iraqi Shia leader Muqtada al-Sadr’s list won the most votes in Iraq’s parliamentary elections on May 12. (Reuters/Alaa Al-Marjani)