The United States, working with its allies, must gradually ramp up economic sanctions on Venezuela as part of a strategy to change Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s authoritarian behavior, according to an Atlantic Council analyst.

The United States, working with its allies, must gradually ramp up economic sanctions on Venezuela as part of a strategy to change Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s authoritarian behavior, according to an Atlantic Council analyst.

“The goal of the sanctions is to change the calculus of President Maduro and his supporters… so they realize there are much more significant costs to his government pursuing these undemocratic steps,” said David Mortlock, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center. However, he added, “those sanctions must be accompanied by a clear narrative” of what the United States and the international community expects to see change.

“The end goal here is not the sanctions themselves but a negotiated diplomatic solution,” said Mortlock, adding that the cost to all governments, to the oil sector, and to the global economy, should Venezuela collapse due to unrest and economic recession, “is too great to simply step back and let Venezuela continue down this path.”

Venezuela has been plagued by civil unrest, political repression, and humanitarian crisis. Amidst protests which have killed over 120 civilians and widespread hunger throughout the country, Maduro held an illegal vote on July 30 to elect a new Constituent Assembly, comprised of those loyal to the government. This new governing body will be able to eliminate any further democratic checks on the president’s power, leading Venezuela further down the path to authoritarian rule.

On August 8, foreign ministers from seventeen different countries in the Western hemisphere—including Mexico, Argentina, and Canada—convened in Lima, Peru, to discuss the escalating situation in Venezuela. They declared their governments will refuse to recognize Venezuela’s new Constituent Assembly.

According to Francisco Monaldi, a fellow in Latin American Energy Policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, this agreement—the Lima Declaration—is indicative of the international community “laying groundwork for how they want the Venezuelan government to change paths.”

Mortlock and Monaldi spoke together on a conference call, moderated by Jason Marczak, director of the Latin America Economic Growth Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, to discuss the options available to the United States and its partners as they attempt to stem what Marczak labeled the “deepest diplomatic rupture yet” in Venezuela.

However, Monaldi cautioned, “all this should be done… as part of a diplomatic effort with a clear narrative and clear goals.”

On July 31, the United States imposed financial sanctions on Maduro, making him the fourth head of state currently under sanctions by the United States. The other three are Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un.

The United States has also imposed economic sanctions on a number of individuals in Venezuela who are close to the government in an attempt to induce Maduro to halt the erosion of democracy. However, despite US sanctions slapped on Maduro for his abuses of power, the new Constituent Assembly’s first act was the ouster of Venezuela’s Chief Prosecutor Luisa Ortega Díaz, an outspoken critic of the government. Given the course of events, “it is quite likely we’ll see more of that,” said Mortlock.

Now the administration of US President Donald J. Trump is weighing the possibility of imposing sanctions on Venezuela’s energy sector. As the country with the world’s largest oil reserves, Venezuela would be crippled by sanctions targeting energy, a pillar of their economy.

Mortlock and Monaldi discuss the array of sanctions options available to the United States in their latest publication: Venezuela: What are the most effective US sanctions?

Sanctions are “a useful tool that the United States can deploy here to pursue [a] diplomatic solution in Venezuela,” said Mortlock. He described how the United States should be serious about taking steps that impose real costs on the Venezuelan government, but also indicate that they are willing to increase those costs over time if Maduro does not change course.

Both Mortlock and Monaldi insisted that while the sanctions should continue to ramp up in severity, they should also include an off ramp, making it possible for Maduro to get Venezuela back on a democratic track.

The United States has already sanctioned Maduro and many individuals close to him, however, next steps could include the banning of exports and imports between Venezuela and the United States. Such measures would have a severe and immediate impact on the Venezuelan economy, already in a crippled state.

“The import ban is the biggest weapon,” said Monaldi. US goods and services trade with Venezuela totaled an estimated $22.9 billion in 2016—exports were $11.2 billion, while imports totaled $11.7 billion.

Should Venezuela find itself unable to export oil to the United States, it “will have to divert those exports to mostly Asia,” said Monaldi. He described how this would result in higher transport costs and lower prices in order to compete in a new market.

The ban on Venezuelan imports would also negatively impact the US economy, said Mortlock, as well as the economies of any country which also signed on to the ban. Implementing multilateral sanctions with broad support “requires a strenuous diplomatic life to get other countries to go along with you,” he said. According to Monaldi, “in terms of the broader diplomatic efforts, it’s important to involve Latin America.” In this regard, he said, the Lima Declaration is a step in the right direction.

While a US representative was not at the table in Lima, that does not mean Washington is leaning back from the issue, said Marcak. Rather, he said, US officials are working behind the scenes in coalition with regional partners, to galvanize Latin American countries to take further actions against the Venezuelan government.

The next step, beyond banning imports and exports, would be to sanction PDVSA, Venezuela’s national oil company. PDVSA generates 95 percent of Venezuela’s foreign exchange. Should the United States add PDVSA to the List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN List), it “would have an effect equivalent or worse than the combined effect of all the other sanctions mentioned,” Mortlock and Monaldi write. Such a measure could lead Venezuela into the worst recession in Latin America in recorded history, they said.

According to Monaldi, polls “seem to point to the fact that Venezuelans are worried… about economic sanctions.” In a country wracked by lack of food and medicine where thousands flee across the Colombian border every day, people worry that US sanctions could further deteriorate their standard of living, he said.

Monaldi cautioned that any sanctions imposed by the United States or international governments must be done in such a way as to minimize the negative impact on the people of Venezuela. Sanctions “could be gradual and targeted so that [they] affect a minimal portion of the population,” said Monaldi. According to Mortlock, “all of these options can be rolled out in a way to minimize the negative impact on the US and Venezuelan people.”

However, Monaldi added, regardless of the measures taken, “it will be necessary for the humanitarian community to offer humanitarian help.”

While Maduro has refused humanitarian aid in the past, it would undermine his current argument that the current ills of the country are due to economic pressure from the United States should he block further assistance, said Mortlock.

When former US President Barack Obama imposed sanctions on seven Venezuelan government officials in 2015, the Venezuelan people placed the blame for their economic situation on Washington. However, “as events have evolved… it would be harder for the government to sell the notion that the US or external forces are to blame for some of these sanctions,” said Monaldi.

Rachel Ansley is an editorial assistant at the Atlantic Council.

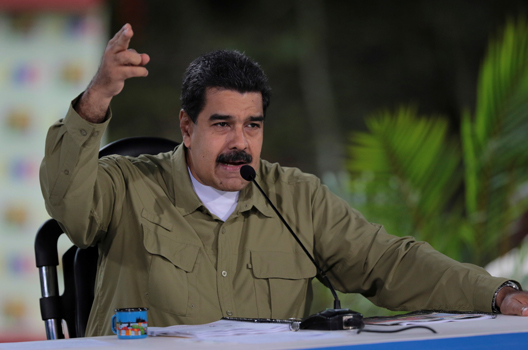

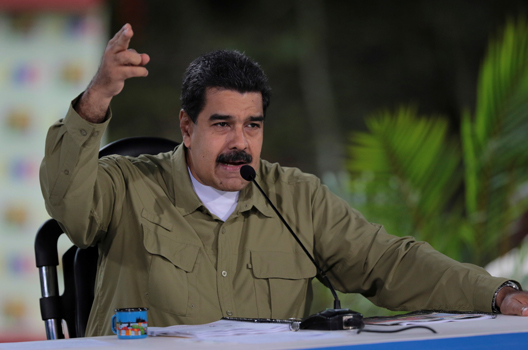

Image: Venezuela's President Nicolas Maduro speaks during his weekly broadcast "Los Domingos con Maduro" (The Sundays with Maduro) in Caracas, Venezuela August 6, 2017. (Miraflores Palace/Handout via REUTERS)