Since the failure of a brief effort at engaging Iran, the Obama administration has pivoted to economic pressure, piling sanction after sanction on the Islamic Republic to try to persuade it to curb a program that could give it the capacity to make nuclear weapons.

Last week, the U.S. penalized seven foreign companies for selling gasoline to Iran, on top of two targeted for dealings with Iran last year. All nine were sanctioned under the 2010 Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability and Divestment Act, the most thorough and biting U.S. legislation against Iran since the 1979 revolution.

Yet among the companies sanctioned, not a single one was Chinese despite the fact that China supplies about a third of Iran’s imported gasoline, according to the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington research and advocacy group. China is also Iran’s biggest single trading partner and largest investor in the oil and gas sector on which the Iranian economy relies.

An investigation by the Atlantic Council’s Iran Task Force released Thursday concludes that the sanctions against Iran will not succeed as long as the price of oil remains high and China continues its extensive involvement in the Iranian economy, in particular its oil and gas industry.

China voted for and is implementing four United Nations Security Council sanctions resolutions passed against Iran in recent years. But China has not followed the United States, Europe, Japan and Australia in imposing further measures that would have a real impact on Iranian decision makers. Under intense U.S. pressure, China has slightly scaled back its purchases of Iranian oil and slowed investment in the oil and gas industry to make it easier for the Obama administration to waive penalties against Chinese companies under CISADA. However, Beijing has made it clear that it will only go so far.

Diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks show that China has warned the U.S. not to touch its energy companies or face unspecified but presumably dire consequences. A March 2008 cable quotes Chinese Arms Control Director General Cheng Jingye telling Senate Foreign Relations Committee East Asia specialist Frank Jannuzi that “China has made clear its need for energy resources and has previously stated that its cooperation with Iran on energy has nothing to do with the Iran nuclear issue. … The threat of sanctions against Sinopec [a major Chinese oil company] is a very serious issue. … Sinopec is very important to China and Cheng ‘can’t imagine’ the consequences if the company is sanctioned.”

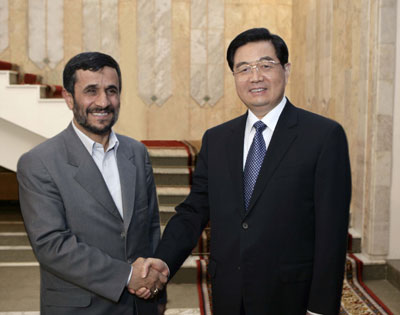

China is ambivalent about Iran’s nuclear progress and appears to value its relationship with a major power in the Persian Gulf more than it does global concerns about proliferation.

John W. Garver, an expert on Chinese-Iranian relations at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology, has argued that China is playing a “dual game,” seeking to retain access to “Iran’s fabulously rich but still largely unexploited oil and gas resources to meet China’s skyrocketing demand for imported energy” while also trying to stay on good terms with the U.S. in order “to maintain a favorable macro-climate for China’s development drive.”

Garver believes some officials in China would actually prefer Iran to develop nuclear weapons, because “a strong Iran resistant to U.S. dictates and at odds with the U.S. would force Washington to keep large military forces in the region, limiting the ability of the U.S. to concentrate forces in East Asia, where China’s core interests lie.”

To facilitate a diplomatic resolution of the Iranian nuclear issue, the U.S. and its allies should show greater flexibility and propose a trade-off that would allow Iran to retain a program of limited uranium enrichment under rigorous international safeguards. If Iran refuses such a compromise, the international consensus against it will only be strengthened.

If sanctions are to succeed, the U.S. must also persuade China to use its growing economic leverage over Iran to encourage it to accept a diplomatic solution. It is in China’s best interest as a rising great power to show that it has the ability to broker such deals, and that domestic economic growth — and bogging down the U.S. military in the Middle East — are not Beijing’s only preoccupations.

Otherwise, Iran is likely to continue its nuclear march, and strains will grow between the world’s two biggest and most influential economies.

Barbara Slavin is a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center. This article originally appeared on Politico.

Image: CHINA_Sco_1.jpg