Winston Churchill declared, “In war-time, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.” In the current environment, it’s difficult to know where the truth ends and the lies begin. Last week the Washington Post reported, “The National Security Agency has broken privacy rules or overstepped its legal authority thousands of times each year since Congress granted the agency broad new powers in 2008.” But that report shed more heat than light on a contentious subject.

Winston Churchill declared, “In war-time, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.” In the current environment, it’s difficult to know where the truth ends and the lies begin. Last week the Washington Post reported, “The National Security Agency has broken privacy rules or overstepped its legal authority thousands of times each year since Congress granted the agency broad new powers in 2008.” But that report shed more heat than light on a contentious subject.

More than two months after Edward Snowden’s revelations, we still do not know the scope of the NSA’s surveillance programs. Quite probably, we never will. But the hue and cry over the NSA’s internal investigation finding all manner of violations of the law is misplaced. In fact, the uproar is strong evidence of an agency that takes its responsibilities to comply with the law seriously.

Benjamin Wittes, a senior fellow at Brookings and editor of its Lawfare blog, puts it quite succinctly:

[The report] should give the public great confidence both in NSA’s internal oversight mechanisms and in the executive and judicial oversight mechanisms outside the agency. They show no evidence of any intentional spying on Americans or abuse of civil liberties. They show a low rate of the sort of errors any complex system of technical collection will inevitably yield. They show robust compliance procedures on the part of the NSA. And they show an earnest, ongoing dialog with the FISA Court over the parameters of the agency’s legal authority and a commitment both to keeping the court informed of activities and to complying with its judgments on their legality.

While Wittes is “annoyed” by the hyped framing of this discussion in the media, he’s more frustrated by “the administration’s weedy and defensive response,” which has made the wildest claims seem plausible.

While we’re in full agreement on that score, it’s perhaps a bit unfair given the uneven playing field. Most of what the public knows about the matter, including this latest release, comes from selective, criminal leaks of classified data by an erstwhile defense contractor hiding out in Russia while claiming to be a whistleblower. Meanwhile, those who would defend the program either don’t know all that much about it or are limited in what they can say about it precisely because it’s classified.

Then there is Senator Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat who sits on the intelligence committee. He has been an outspoken critic of these programs in general and about misleading statements from intelligence community leaders in particular. In a speech at the Center for American Progress, he asked, “When did it become all right for government officials’ public statements and private statements to differ so fundamentally?” The question was apparently rhetorical: “The answer is that it is not all right, and it is indicative of a much larger culture of misinformation that goes beyond the congressional hearing room and into the public conversation writ large.”

While I share some of Wyden’s misgivings about the scope of the government’s collection of information on American citizens, and indeed the general weakening of the Bill of Rights in the fight against global terrorism, this charge strikes me as naive, if not silly. By its very nature, a culture of misinformation follows a culture of secrecy as night follows day. As Churchill understood, questions will come up and misinformation is necessary to divert people from stumbling on the truth.

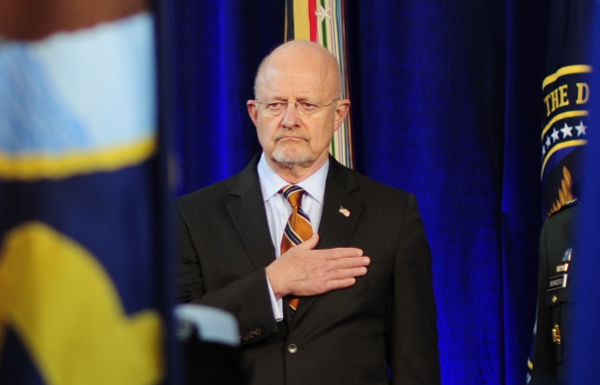

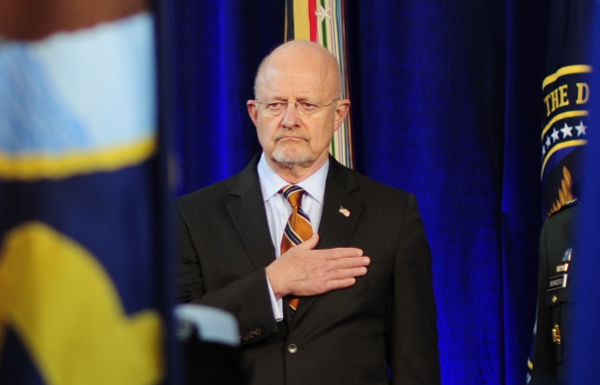

Indeed, Wyden himself unwittingly demonstrated this recently. He was justifiably upset that Director of National Intelligence James Clapper told him that the NSA was “not wittingly” collecting data on millions of Americans when, in fact, it was and Clapper knew it. That the intelligence community defines “collect” in a different way than the dictionary doesn’t change the fact that Clapper was intentionally trying to hide the existence of the program.

Then again, Wyden should have known better than to ask that question in a public hearing. It would not only have been foolish but illegal for Clapper to acknowledge the existence of a highly sensitive and classified program in that setting. So, Clapper was put in a position where he had to either lie or give an answer that tacitly revealed classified information. (Truthfully denying one program and then giving a “I can neither confirm nor deny” response regarding another makes it rather clear that the second program exists.) Clapper tried to avoid either path by giving an answer that was too cute, seemingly denying the program existed while not quite doing so. That was foolish and he was later forced to apologize.

The bottom line here is that, while some members of Congress are entitled to know what our intelligence community is doing, “Congress” isn’t. Some information is shared only with the chairman and ranking member of the House and Senate intelligence committees. Some is shared with the committees in whole but only behind closed doors, in sessions where they’re sworn to secrecy. Very little information is shared in public hearings and, frankly, we probably shouldn’t put too much in what is.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council. This piece first appeared in The National Interest.

Image: Photo: US Air Force