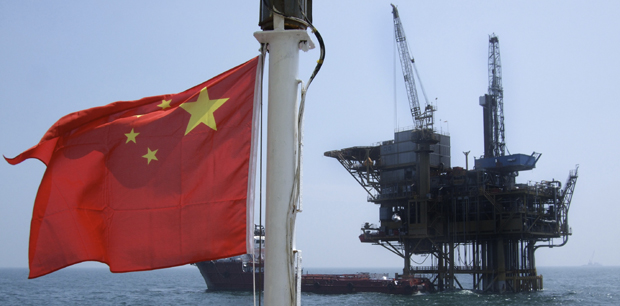

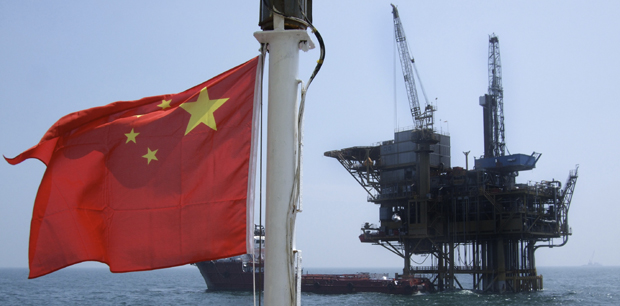

This, at least, is how Wang Yilin, Chairman of the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), chooses to view them. He reportedly told an audience at CNOOC’s headquarters in Beijing in May that ‘large-scale deep-water rigs are our mobile national territory and a strategic weapon’.

This writer is no Sinologist and lacks the qualifications to parse his words for hidden meanings. At the same time people are all-too familiar with the sound of public figures “misspeaking’. Nonetheless, it appears prudent to assume that the man knew what he was saying and that we should accept his words at face value. If we do we should be disturbed.

Six concerns spring to mind.

First, that the statement appears to reflect the mercantilist thinking of China’s ruling elite. Mercantilism, the trading philosophy that prevailed before open markets, saw wealth as limited and trade and national power as linked such that it was not enough for one state to win commercially and therefore politically, the other state had to loose. Consequently, when it comes to China’s great commercial corporations such as CNOOC they should not be regarded as being like modern Western companies but as arms of a competitive state in which profit-maximization sits uncomfortably alongside the need to further Chinese state policy, whatever that might happen to be at the time.

Second, the legal position is unclear: the CNOOC Chairman is asserting something that does not exist as there is nothing in the law of the sea that recognizes platforms or structures as sovereign territory, even though they are considered under title i.e. ownership of the state that put them there. In general they have much more salience in the political than in the legal realm and this appears to be what China is attempting to expand. Chairman Yilin’s language suggests that China’s intends using CNOOC platforms to slowly wrest control of offshore areas by creating an ambiguous political-legal aura of authority and control. Possession is nine-tenths of the law in any language and if China – as in the game of Go – can establish an advantageous position then it will do so.

Third, how this view of oil rigs as ‘strategic weapons’, and this peculiar interpretation of their legal status, coincides with China’s ‘Three Warfares’ thinking. The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) in its 2011 Annual Report to Congress on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China described this as a three-pronged offensive strategy based on:

- Psychological Warfare, which seeks to undermine an enemy’s ability to conduct combat operations by deterring, shocking, and demoralizing enemy military personnel and supporting civilian populations;

- Media Warfare that is aimed at influencing domestic and international public opinion to build support for China’s military actions and dissuade an adversary from pursuing actions contrary to China’s interests; and

- Legal Warfare that uses international and domestic law to claim the legal high ground or assert Chinese interests, employing both to hamstring an adversary’s operational freedom and shape the operational space. Legal warfare is also intended to build international support and manage possible political repercussions of China’s military actions.

A fuller account of this thinking can be found here.

Fourth, the implications of this thinking – and CNOOC’s state-directed role in advancing China’s national interests – in the current disputes in the South China Sea. China is looking to control 80% of its area and is prepared to use all arms of national power – diplomatic, military, paramilitary and commercial – to get what it wants. The starting point is an historic claim which is usually delineated by the so-called ‘nine-dash line’ based on a similar line drawn up by the previous nationalist regime. This line and China’s claims are contested by Vietnam and the Philippines particularly but by other littoral states as well.

A semi-submersible deep-water rig of the type China launched in May – the Haiyang Shiyou 981 (HYSY 981) – and which Chairman Yilin was celebrating when he spoke about a ‘strategic weapon’, would give China access to all but the very deepest seabed areas within the line. The Stimson Center and Collins and Erickson writing in China SignPost, both believe that for the present China will not deploy such a vulnerable asset outside its undisputed EEZ even though the rig now enables it to undertake drilling operations in the deep waters off the Vietnamese coast.

Collins and Erickson (who provide a useful map illustrating how HYSY 981 extends China’s exploratory range) take the view that

‘for the near future CNOOC’s deepwater drilling operations will remain in the Liwan trough and other areas that lie unequivocally within China’s EEZ. For Beijing, the diplomatic costs of drilling in a disputed zone such as the Spratlys against the wishes of the other claimants would likely substantially exceed the additional oil or gas production gained. Even a large new oilfield producing 200,000 bpd or more in a disputed zone would not be worth drilling unilaterally if doing so catalyzed further development of anti-China regional security alignments.’

‘for the near future CNOOC’s deepwater drilling operations will remain in the Liwan trough and other areas that lie unequivocally within China’s EEZ. For Beijing, the diplomatic costs of drilling in a disputed zone such as the Spratlys against the wishes of the other claimants would likely substantially exceed the additional oil or gas production gained. Even a large new oilfield producing 200,000 bpd or more in a disputed zone would not be worth drilling unilaterally if doing so catalyzed further development of anti-China regional security alignments.’

This may be true for the moment given that despite its provocative stance vis-a-vis the Philippines off the Scarborough Shoal, and despite the failure of the ASEAN nations to maintain a united front in the face of its brazen manipulation, China lacks the resources to defend the whole of its claim militarily. That it is working to change this is indisputable.

At the same time China – through the agency of CNOOC – has for the first time invited tenders for oil and gas exploration blocks in disputed waters off Vietnam’s coast. These blocks overlap already proclaimed Vietnamese blocks. The consequent uncertainty means that in all likelihood there will be few takers for what is on offer, certainly from major oil companies with the necessary deep-water technology and expertise. Suggestions that this move revealed a lack of policy coordination between the Chinese foreign affairs ministry and CNOOC may, or may not, be true with CNOOC acting on the basis that China’s right to everything within the ‘nine-dash line’ is unarguable just at the moment the foreign ministry was taking a somewhat more conciliatory line. Whichever interpretation proves correct, China is still sending a signal to Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries that it will proceed on its terms; one that is reinforced by the declaration of a new prefecture covering the Paracel and Spratly Islands and an increase in the size of the PLA garrison on the tiny Woody (or Yongxing) Island.

At the same time China – through the agency of CNOOC – has for the first time invited tenders for oil and gas exploration blocks in disputed waters off Vietnam’s coast. These blocks overlap already proclaimed Vietnamese blocks. The consequent uncertainty means that in all likelihood there will be few takers for what is on offer, certainly from major oil companies with the necessary deep-water technology and expertise. Suggestions that this move revealed a lack of policy coordination between the Chinese foreign affairs ministry and CNOOC may, or may not, be true with CNOOC acting on the basis that China’s right to everything within the ‘nine-dash line’ is unarguable just at the moment the foreign ministry was taking a somewhat more conciliatory line. Whichever interpretation proves correct, China is still sending a signal to Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries that it will proceed on its terms; one that is reinforced by the declaration of a new prefecture covering the Paracel and Spratly Islands and an increase in the size of the PLA garrison on the tiny Woody (or Yongxing) Island.

Fifth is how this view of the world, and the concomitant view of oil rigs as strategic weapons, could play out in more distant waters where China has similar natural resource interests. Pertinent examples are the emerging oil and gas province off East Africa and the seabed mineral deposits in the South-West Indian Ocean for which the UN International Seabed Authority recently granted China an exploratory license. It is unlikely that China will behave as aggressively in these areas as it is being in the South China Sea, but the grant of the mineral license has nonetheless provoked worries in India about an enlarged Chinese Indian Ocean naval presence. What its words (and actions) reveal is that it continues to regard the sea as territory, as compared the Western view that has prevailed for the past 300 years of the sea as space open to all subject only to limited restrictions. China attempted to assert its view during the negotiations which resulted in the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) but failed to have it accepted. Some states are nonetheless sympathetic to its position and, while none assert it as vigorously as China, may well be tempted to follow its lead if it crushes the objections of its neighbors and gains the level of control over the South China Sea to which it feels it is entitled. If its does, and its ‘blue water’ naval capability expands, then it is likely it will be able to subtly shift the international rules governing the maritime domain in its favor.

Sixth and finally, Chairman Yilin’s words do not square with CNOOC’s statement to the Wall Street Journal that it is ‘respectful of the regulatory requirements across all the respective jurisdictions’ and that it aims ‘to cooperate with all regulatory authorities.’ Why this is relevant to the United States is because CNOOC is attempting to buy a large Canadian energy company, Nexen, in a deal worth $15.1 billion. US regulatory approval is required because Nexen has assets in the Gulf of Mexico. While there are good reasons to allow the purchase – the Chinese are arguably over-paying (60% premium over pre-deal stock price) – nonetheless Nexen does have deep-water extractive technology that will help CNOOC in the South China Sea and elsewhere, and could allow it to maximize the return on its investment in HYSY 981 more quickly that it would be able to do otherwise. Is this in the interest of the United States? More particularly, how does approval – and the Obama Administration’s strange reluctance to challenge China’s political posturing in maritime matters – help its Southeast Asian allies who may, sometime in the near future depending upon how the negotiations in which China is aiming to pick them off one-by-one play out, see this rig and others like it parked in waters for which previously they had a valid claim?

Dr. Martin N. Murphy is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Michael S. Ansari Africa Center. This piece was originally published on Murphy’s blog Murphy on Piracy.

Image credit China oil rig: iStockphoto

Image credit Woody Island: Paul Spijkers

Map credit: China SignPost