After nearly two years of complex negotiations, the United States and India are close to securing a narrow trade deal that would strengthen commercial ties between Washington and New Delhi. Yet as negotiators prepare for the final stage of the talks, India’s efforts to advance three new tech policies could emerge as a potential spoiler. Preventing a downward spiral in bilateral trade relations will require India to tread cautiously in its approach to tech policy and delay new measures that would disrupt a trade deal.

Indian tech policy looms over the trade talks

While India’s tech policies are not the focus of the current trade talks, they loom over the discussions as a potential powder keg. Indeed, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) has threatened to conduct a Section 301 review of India’s market access barriers in response to new tech sector policies that negatively impact US companies, such as proposed data localization measures or broad restrictions on e-commerce companies. If initiated, such a review would pave the way for additional U.S. tariffs on India and almost certainly destroy any prospect of a short-term trade deal.

In this context, USTR has positioned the Section 301 review as a critical inflection point and policy deterrent. It has placed the onus on New Delhi to modify its approach to tech sector regulation or risk derailing a trade deal altogether.

Three potential landmines

USTR’s calculus may soon be put to the test. In the coming weeks, the Modi government is poised to advance three tech policies that will likely impose onerous restrictions on US firms. Each of these measures could convince USTR Robert Lighthizer to greenlight a Section 301 review:

- Personal Data Protection Bill: India’s Cabinet formally approved the Personal Data Protection Bill on December 4, setting the stage for its introduction in Parliament this week. If passed, the bill would radically overhaul data governance in India, impose strict data localization measures on US tech companies, and establish a new Data Protection Authority that could enforce new compliance requirements with steep monetary penalties. USTR is closely tracking the bill to assess potential risks to US firms and the need for a Section 301 response.

- E-Commerce policy: India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOCI) has revived efforts to develop a comprehensive e-commerce policy that could introduce new data localization restrictions, potential requirements for disclosure of source code, and broad restrictions limiting pricing strategies of multinationals. US companies have yet to see a revised version of the e-commerce policy, which the MOCI previously suggested would be completed by June 2020. A sudden push to accelerate the e-commerce policy—especially as domestic interest groups launch coordinated protests against Amazon and Walmart—could lead USTR to examine a Section 301 review.

- Intermediary guidelines: Alongside the Personal Data Protection Bill, India has led a high-profile push to develop new guidelines for intermediary platforms and social media companies to prevent sharing of dangerous content and promote cooperation with law enforcement. US social media companies have criticized the proposed measure for introducing mandatory “traceability” requirements that would require them to create backdoors into code and break end-to-end encryption protections. While US officials share Indian concerns around encryption, New Delhi’s attempts to advance the policy using a questionable legal basis and a targeted public focus on WhatsApp have generated significant attention internationally and could trigger further pushback from USTR.

Recommendations for New Delhi

In the current political and economic climate, the Modi government is likely to face strong domestic pressure to advance each of these three policies rapidly. This, in turn, will create incentives for bureaucrats or parliamentarians to limit additional stakeholder consultations, internal deliberations, and industry engagement. New Delhi would be wise to resist these pressures and exercise restraint. Instead, it should recognize the potential impact of tech policy on the US-India trade deal and take a measured approach to tech sector regulation across three important dimensions.

First, India should privately commit to a six-month moratorium on new tech policies, including the three measures outlined above. This would give trade negotiators adequate time and space to finalize the long-sought trade deal and set the stage for additional trade talks covering a wider set of issues. To secure political buy-in for such a concession, New Delhi could offer the moratorium in exchange for a reciprocal US moratorium on a Section 301 investigation that would last six months.

Second, ministry officials and parliamentarians should use the six-month period to launch a series of new stakeholder consultations on the Personal Data Protection Bill, e-commerce policy, and intermediary guidelines. This would require Indian ministries to publicly release the latest drafts of these bills and policies, which would help ease some of the uncertainty facing US companies by itself.

Third and finally, Indian trade officials should establish a dedicated dialogue with the United States to address differences on tech policy issues that are likely to continue in the years ahead. This concept has already emerged in the context of the present trade talks and it offers New Delhi a valuable platform to raise its own tech sector priorities with Washington. New Delhi should embrace this platform and urge Washington to do the same.

Ultimately, India and the United States have great opportunities for cooperation as economic partners and digital powerhouses. If restraint from New Delhi can help unlock the full potential of this partnership, it is a risk well worth taking.

Anand Raghuraman is an associate at The Asia Group, LLC.

Further reading:

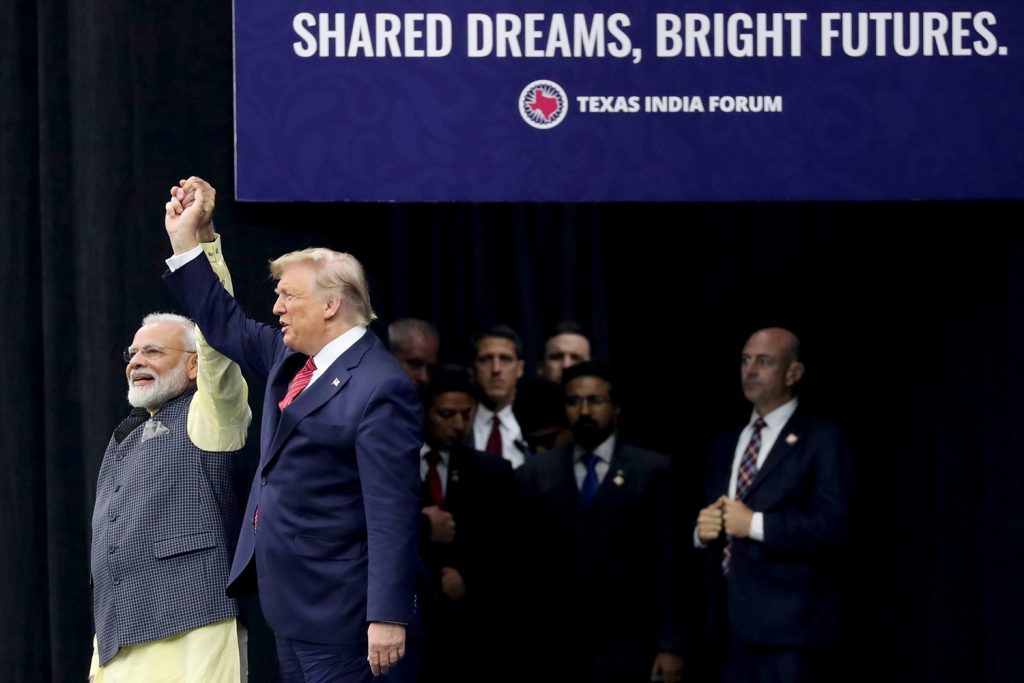

Image: US President Donald Trump and India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi gesture during the "Howdy Modi" event in Houston, Texas, U.S., September 22, 2019. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst