One of the most infuriating arguments to emerge out of the whole Egypt situation is the notion that somehow the Obama Administration was insufficiently engaged. I could link a dozen prominent examples of this argument, but I’m sure you’ve all seen them. The argument is basically, that Obama was too tentative, “behind the curve,” and so on.

I don’t think most people making this argument even quite understand the underpinning of their argument. So let me enunciate it. If you think Obama was too slow to response, you are assuming that an American intervention was both appropriate and potentially effective. As far as I can tell, neither is the case.

First, appropriateness. This is an Egyptian issue to be resolved primarily by Egyptians. Does the United States have interests in regards to Egypt? Of course. But does that mean that we ought, as a result, to take it upon ourselves to try to shape developments there? Not necessarily. At some point, you need to step back and respect the principle of self-determination.

Second, respecting the principle of self-determination is not just a good moral principle, it actually serves long-term U.S. national interests. The reality of the situation is that Egypt remains poised on a knife-edge. A lot of people are worried about a takeover by Islamist radicals. I don’t believe that is particularly likely, though it is certainly within the range of the possible. More likely, we’ll see continued military dominance with a facade of civilian control. Pakistan might be a model. Best case, I suspect is Turkey, where the military serves to constrain policy choices, but remains generally at arms-length. The lack of a clear organizing philosophy for such an army role, however, makes that unlikely. But the point is, it is hard to imagine that what emerges now is somehow going to be particularly stable, and if it is stable, it is unlikely to be popular. So, why would Americans want to own any responsibility for that outcome?

Yes, I know we’ll be blamed for anything that goes wrong. But I don’t accept that just because some will blame us, that we ought to fatalistically be resigned to that. We need to think about the long-game with Egypt, and our position in the long-game will not be materially improved by us seeming to have our fingers too visibly on the scales. We’re still paying for our intervention in Iranian politics in 1953! And at least then we had a coherent — though in retrospect misguided in that specific case — Cold War strategic rationale for our actions. In the case of Egypt today the demand for a more forward-leaning posture is really nothing more than a reflexive impulse to primacy combined with a vague and poorly-reasoned conception of the requirements of preventing terrorism.

Third and finally, there is little reason to believe that the United States is in a position to materially affect outcomes in Egypt. There are powerful forces within that country at work, and our influence is limited. And a practical matter, the best possible message we can send to the Egyptians (and the world) is precisely that we are not in control of the situation, that like everyone else, we wish the Egyptians well, are anxious about the situation, but in the final analysis are simply observers rather than players in the process.

Too long, didn’t read version: Despite the desire to “do something,” a greater involvement by the United States in Egypt is wrong, unwise, and likely to be ineffective.

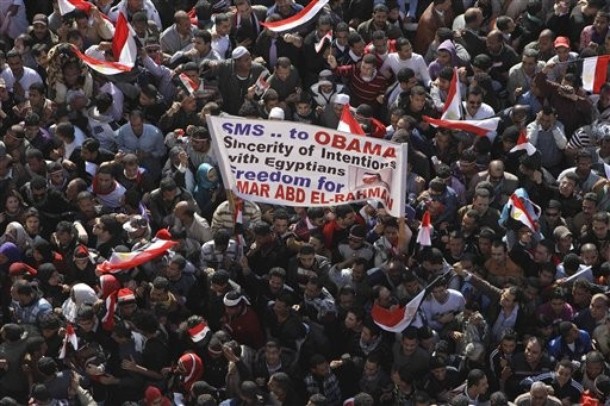

Dr. Bernard I. Finel, an Atlantic Council contributing editor, is Associate Professor of National Security Strategy at the National War College. His arguments are his own and do not represent the views or opinions of the National War College, National Defense University, or the Department of Defense. This was originally posted on his personal blog BernardFinel.com. Photo credit: AP Photo.

Image: obamarahman.jpg