President’s plan for state of emergency could further reduce space for dissent, said Atlantic Council’s Mirette Mabrouk

Egyptian President Abdul Fattah el-Sisi’s decision to impose a three-month state of emergency in response to deadly church bombings will likely further shrink the space for freedom of expression and dissent in Egypt, according to Mirette Mabrouk, director of research and programs at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

“The space for freedom of expression and dissent in Egypt has already shrunk considerably. I can’t imagine that this is to going help,” said Mabrouk. The state of emergency, which must first be approved by parliament, would allow security forces to monitor people’s social media and communications without permission, but after the president has issued a verbal or written order.

Sisi’s relationship with the United States grew frosty on US President Barack Obama’s watch amid concerns in Washington about the military coup that brought Sisi, then a general, to power on July 3, 2013, and the bloody crackdown that followed on August 14, 2013, which killed an estimated 817 peaceful demonstrators in Cairo’s Rabaa al-Adawiya Square.

The Obama administration responded to these developments by temporarily suspending joint military exercises and the delivery of major weapons systems to Egypt. Following the ouster of Egypt’s longtime ruler Hosni Mubarak in 2011, the US Congress conditioned US military aid to Cairo on Egypt taking steps to protect human rights and ensure a democratic transition to a civilian government. However, in most years since that agreement the US secretary of state has waived these conditions, citing US national security interests.

On April 3, Sisi was rewarded with a White House meeting with US President Donald J. Trump. In that meeting, Trump delivered a strong expression of support for Sisi. “He’s done a fantastic job in a very difficult situation,” said the US president.

Human rights groups disagree. They estimate that the Egyptian government has detained at least 41,000 and possibly as many as 60,000 people since the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, was ousted by Sisi on July 3, 2013.

ISIS and Egypt

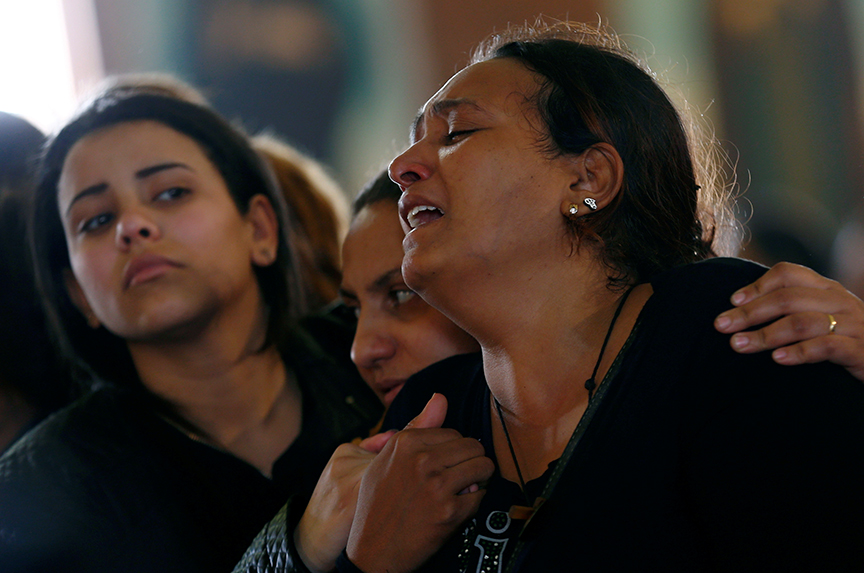

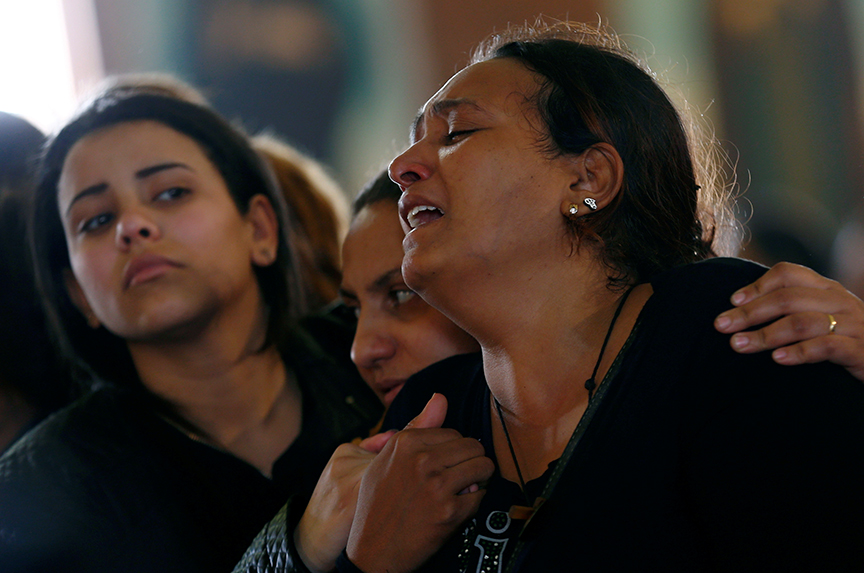

The so-called Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) claimed responsibility for the blasts in Tanta and Alexandria on Palm Sunday. As many as forty-four people were killed.

“ISIS is up to the same thing in Egypt as it is anywhere else—destabilization and possibly recruitment,” said Mabrouk.

The group’s modus operandi is to intimidate civilians through acts of terrorism, stir up anger against the government, and radicalize local populations. “It’s a vicious circle,” said Mabrouk.

The attack on April 9 targeted minority Christian Copts, a particularly vulnerable target for Islamic terrorists. “Terrorists will try and go after the Copts because they can use the old ‘Oh, they’re not Muslims’ excuse,” said Mabrouk.

Targeting Copts is a “sure way of [ISIS] raising their own flag,” she said. Noting that the extremist group had also attempted to bomb a mosque in Tanta, she added, “they are expanding their net and trying to wreak havoc.”

While Egypt’s security forces have been criticized for being ill-equipped to take on the challenge posed by ISIS, Mabrouk noted that no city in the world is immune to acts of terrorism. In Stockholm, for example, an attacker rammed a stolen beer truck into a crowd of people killing four and injuring fifteen others on April 7; and on March 22, an attacker rammed his car into pedestrians near Parliament in London and stabbed a police officer, killing a total of five people.

“Terrorism is now an ugly fact of life. The only thing that can be done is to remain vigilant,” said Mabrouk.

The Islamic State-Sinai Province, a Salafi jihadist group, was formed in Egypt and the Gaza Strip in 2011. After Mubarak was ousted in an Arab Spring—pro-democracy—uprising in 2011, Islamic State-Sinai Province rushed to fill a vacuum created after tribal communities in the Sinai Peninsula drove out security forces.

Acts of terrorism have since occurred beyond the Sinai Peninsula. “People were used to it happening in Sinai, but not so much in Cairo or Alexandria or surrounding governorates,” said Mabrouk.

“The state is going to scramble to keep up with it, but it is simply not possible to cover the entire country,” she said. “So, I am fairly sure something like [the attack on the churches] is going to happen again, because I just don’t see how you can prevent it.”

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications at the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

Image: Relatives mourned for the victims of the Palm Sunday bombings during their funeral at the Monastery of Saint Mina in Alexandria, Egypt, on April 10. (Reuters/Amr Abdallah Dalsh)