The weekend’s European Parliament produced good news for the center-right parties, bad news for the center-left, and good news for radical parties of all stripes.

Election Returns Reporting

Constant Brand and Robert Wielaard offer a breakdown for AP:

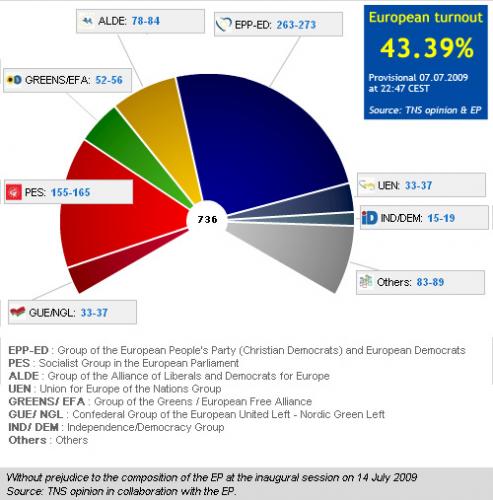

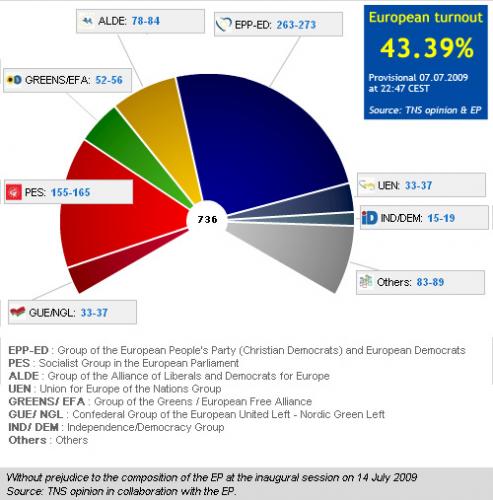

The European Union said center-right parties were expected to take the most seats — 267 — in the 736-member parliament. Center-left parties were headed for 159 seats. The remainder were expected to go to smaller groupings. […] Far-right groups and other fringe parties gained in record-low turnout, estimated at 43.5 percent of 375 million eligible, reflecting widespread disenchantment with the continent-wide legislature.

Euractiv presents the results more graphically:

In a dossier from May, they also present a helpful breakdown of the manifestos of the various parties competing for seats. BBC also has a helpful, interactive guide to groups, broken down on a country-by-country basis, and Deutsche Welle offers a more concise overview.

BBC plays it straight with “Voters steer Europe to the right” as does Deutsche Welle with “Conservatives Sweep European elections.” Neither story offers commentary on the results.

Record Low Turnout

The Economist‘s Charlemagne notes that “overall average turnout has fallen at each and every Euro-election since direct elections were introduced in 1979.” He notes that the European television coverage had MEPs discussing this fact and that they all “began reeling off excuses, and other people to blame,” whether the media or national level politicians. While conceding that these points all have merit, he thinks the message that “we need to keep doing the same thing as before, only more of it. More Europe, more power for the European Parliament, and more taxpayer funded communication of Europe” is wrongheaded.

But having analysed the many reasons why pan-European democracy may not be working, MEPs seem to have an extraordinary ability to ignore the starting point of that analysis: that pan European democracy is not working. Not one seems able to take a step back and wonder if the falling turnout is a signal to accept that voters in each country feel more of a connection with national politics than the European version. There is much that is wrong with national politics. […] But how can anyone look at the turnout trends in Euro-elections and imagine that the answer is more of the same, with no deeper reflection?

An unsigned Euractiv essay, however, dismisses the repeated refrain that low turnout tainted the results:

Despite fears that voter turnout would plunge, participation in these elections remained stable, with 43.39% of voters heading to the polls. In the 2004 elections, it was 45.9%.

Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) leader Graham Watson said the low turnout could be interpreted in two ways: “Either people don’t go to vote because they are perfectly satisfied, or because there must be something wrong.”

“We need to work towards a proper policy of communication about what happens at EU level, give Euronews the status of public station broadcaster in all of our countries, and elect a percentage of the European Parliament on a pan-European list. That might help us to have a European debate, rather than help us to have 27 national debates,” he said.

Asked what effect the low turnout would have on the Parliament’s legitimacy, Professor Mario Telo, president of the European Studies Institute at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), said: “It is incorrect to talk about lack of legitimacy. A possible reading could also be that the European system is so well-established that even Eurosceptic parties want to be represented in the European Parliament.”

The National Security Network’s Max Bergmann, writing Friday before the balloting was over, recites many of the reasons for relatively low interest in the EU elections but thinks that, whatever the cause, it’s a problem.

Europe’s movement toward a more federal union is incomplete and currently stalling. While public apathy is not good no matter where you are, this is a particularly acute problem because for a more cohesive Europe to emerge it will continue to need to evolve and strengthen its federal political system, which will require public support. European apathy and disinterest has been a real obstacle to efforts to streamline the EU, as seen by the inability to push through a new constitution or the Lisbon treaty.

Matt Yglesias of the Center for American Progress sees a transatlantic dimension to the problem:

I increasingly worry that the fairly problematic institutional framework that governs the European Union is going to be a problem for all of us. Without anyone really digesting this information, over the past 10-15 years the United States has been eclipsed by the EU as the world’s most significant economic actor. But the EU in various ways lacks the capacity and legitimacy needed to respond in a forceful way to the global economic meltdown, and the European Central Bank appears to feel an overwhelming need to establish credibility as an inflation-fighter.

What it Means for Europe

The implications of the weekend’s balloting for individual European states and their governments will be the subject of a follow-up post. But what do they mean for Europe and the EU, more broadly.

Times of London uses the ominous headline “European elections: extremist and fringe parties are the big winners” for their coverage by David Charter and Rory Watson.

Extremist and fringe parties were the beneficiaries as voters across Europe deserted mainstream parties or stayed at home in protest at the state of their economies.

The Centre Left was set to be the big loser across the 27 European Union countries with the Centre Right consolidating its position as the largest group in the Parliament. Anti-immigrant parties gained MEPs in Austria, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, the Netherlands and Slovakia.

Governing parties generally suffered but this trend was bucked in Italy, where Silvio Berlusconi’s Party of Freedom was heading for gains, and in France, where Nicolas Sarkozy’s UMP recovered dramatically from a poor showing in 2004.

The turnout of about 43 per cent, compared with the low of 45.47 per cent in 2004, meant that 213 million voters abstained from the poll despite mandatory voting in several countries.

Petra de Koning and Jeroen van der Kris offer a more benign analysis for NRC Handelsblad:

Despite the credit crunch and the resulting economic crisis, Europeans gave a vote of confidence in the free market ideology by voting mostly for centre-right parties in the European parliament polls that closed on Sunday night.

French president Nicolas Sarkozy and Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi have reason to celebrate. German chancellor Angela Merkel did less well, but she was able to minimise the predicted loss. All these leaders belong to the European People’s Party, which looks set to remain the biggest political group in the European parliament.

For the past five years, Christian democrats and conservatives formed a majority with the liberals in the European parliament. This allowed the parliament to approve measures aimed at liberalising many sectors that were previously in the public domain: mail services, railways, telecommunications and energy among them. The socialist group on the other hand warned against the risks of the free market economy. It had demanded stricter controls on hedge funds well ahead of the financial crisis, but to no avail.

[…]

The result is good news for parliament president José Manuel Barroso who is seeking a second term. The socialist group in the parliament was the most critical of Barroso. The Portuguese, who is considered a ‘liberal’ president, already has the support of many heads of government. Europe’s move to the right means that he has a good chance of getting the approval of the European parliament as well.

Time’s Leo Cendrowicz (“Europe’s Voters Reward the Right“) is shocked and awed:

In the midst of a financial downturn, with big government back in fashion and capitalism badly bruised, the left should have swept the European Parliament elections that took place over four days last week. But instead, voters emphatically punished socialist and social-democrat parties — when they could be bothered to show up to the polls.

While there were many messages from the election that took place between June 4 and 7 — including the record low turnout and the rise of the fringe vote — the main one appeared to be a ringing rejection of the centre-left. Across the E.U.’s 27 member states, the story was the same regardless of who the incumbent national government was: voters were shifting rightwards, leaving many social-democrat parties hurting from historic defeats.

The result is almost perverse. At a time when the left’s longstanding complaints about the free market and the lack of workers’ protection are being widely acknowledged and agreed with, voters are turning their backs on those parties that now seem to have been so prophetic. “There is an existential crisis for the socialists. Voters do not want socialism, they want a market system that works,” says Corien Wortmann-Kool, who was re-elected for the Dutch center-right CDA party. “But the socialists are still rooted in the 20th century. They have not yet broken away from their ideological tradition of opposing capitalism.”

BBC Europe editor Mark Mardel, in a post titled “Euroskeptics triumphant,” contends that, “It’s been a tremendous night for those who question the EU’s direction and indeed its existence. “

FT’s Ben Hall signals his thoughts with a piece headlined “Sarkozy to use victory to push EU agenda.”

President Nicolas Sarkozy on Monday vowed to come forward with new initiatives to overhaul the European Union after leading his party to a comfortable victory in European parliamentary elections.

Mr Sarkozy claimed credit for his centre-right UMP party’s success, saying in a statement from the Elysée palace that the way French voters cast their votes showed “their recognition for the work accomplished during the French president of the European Union (last year) and their support for the efforts undertaken by the government to bring to an end an unprecedented global crisis”.

Mr Sarkozy is due to meet Angela Merkel, the German chancellor who is another clear winner of Sunday’s vote, in Paris on Thursday. Mr Sarkozy said he would “take initiatives in the coming days to open up new projects”. The French president is keen to work with Ms Merkel to push forward harmonised financial supervision in the EU, a potential flashpoint at the summit of EU leaders in Brussels later this month.

We shall see how successful Sarzoky is in these ambitions. There’s reason to remain skeptical, however.

While I agree with Yglesias that the EU’s failure to capture the public imagination by now is problematic, it goes to far to say that they are”the world’s most significant economic actor.” It’s true that the EU and USA vie for the title of world’s largest economy and that, epending on the day’s euro-dollar exchange rate, the EU is sometimes out in front. But the fact of the matter is that, while they’ve made a lot of progress, the EU is not a single economy, let alone a unified political entity. And they’re further away from that goal today than they were a week ago.

It’s also worth noting that, while “the right” were the big winners in these elections, “the right” is even less a coherent entity in EU politics than it is in the United States at the moment. While Sarzoky is bullish on consolidating gains and making the EU more powerful (naturally, with France/Sarkozy guiding the way) the center-right parties elected in the UK and elsewhere are decidedly not interested in that agenda.