At 9.3 percent, unemployment in the European Union is at its highest rate in more than a decade. For those under 25, however, the rate is more than twice that.

FP’s Annie Lowrey outlines the problem.

Throughout this decade, Europe has had higher rates of youth unemployment — about 16 or 17 percent — than the OECD average. But until recently, the rate was mitigated by a boom in short-term temporary contract work, which does not always require employers to offer expensive benefits. These jobs went, disproportionately, to young people. By some economists’ estimation, they accounted for most of Europe’s job growth in the past decade.

But these jobs created a generation of young people tenuously employed, with no benefits, severance pay, or guarantees. In France, the group social scientists call “Génération Précaire” earned less, in real terms, than their parents did in the years after World War II. In Britain, the term is the “IPOD” generation: insecure, pressured, overtaxed, and debt-ridden. By 2007, approximately 6 million young people worked temporary jobs. These workers have been the first to go in the recession; the contracts expire, and the work is gone.

And it isn’t just teenagers or dropouts looking for low-skill work who are having trouble finding jobs. People with college and graduate degrees are also struggling, as employers stop hiring new workers altogether. Unemployment among job seekers under 25 in France has risen more than 40 percent in the past year, while total unemployment rose by about 26 percent. A third of Britain’s unemployed are under 25. Youth unemployment is nudging 40 percent in Spain.

The Baltic states, whose bubble burst so dramatically last fall, have seen the greatest increases. In June 2008, between 8.9 and 11.9 percent of young people in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were out of work. As of the last round of reported data, from March and April, those rates stand between 25 and 35.1 percent — about a threefold increase in less than a year.

The European countries with the worst labor markets now — emerging Eastern European economies, like Russia and Latvia — are also those with a proportionately high number of labor-market entrants. Across Europe, a “baby boomlet” or “echo boom” of baby-boomer children means that the ranks of 18-to-25-year-olds have swelled in recent years, heightening the number of young job-seekers.

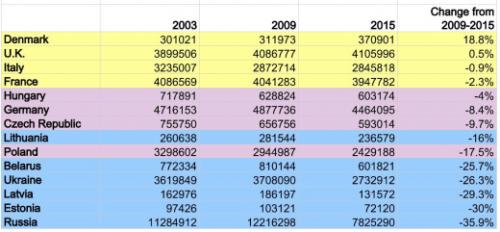

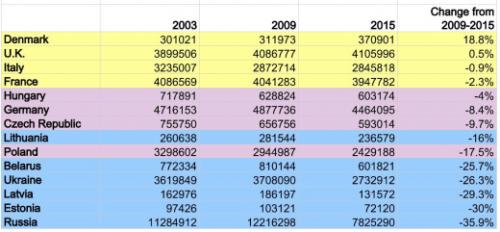

This boom is expected to reverse itself quickly, with a precipitous drop in the young population in mot countries by 2015, as Lowrey demonstrates on this chart:

In the meantime, however, an entire generation could feel permanent effects:

The effects aren’t simply financial. One prominent British think-tanker recently warned, “If this situation persists, the risk may be of a new generation lacking the experience, qualifications, and self-belief to provide for themselves and their families.” Moreover, youth unemployment, much more so than for older workers, carries dangerous social effects: social exclusion, depression, poorer health, social disruption, and higher incidences of crime, incarceration, and suicide. With every month a teenager is unemployed, for instance, his or her likelihood of being convicted of a crime increases.

Whether these statistics will hold true when unemployment is so common within one’s age cohort remains to be seen. But it’s a huge problem regardless.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council.