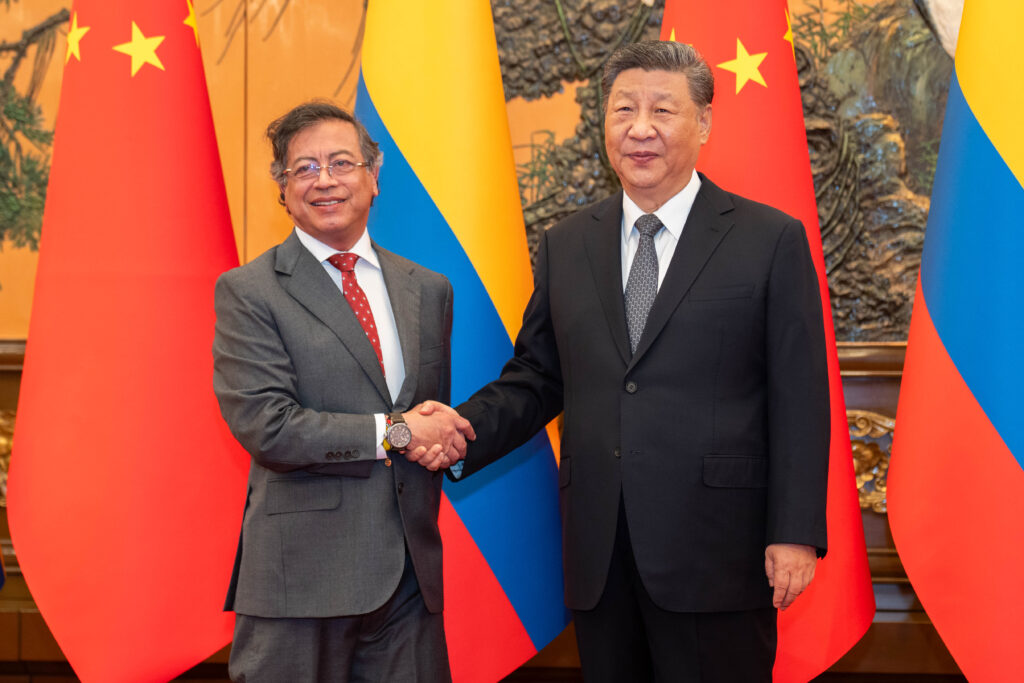

What’s the price of influence? On Tuesday, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced $9.2 billion worth of credit to Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries. Xi made this announcement at the China-CELAC Forum in Beijing, an annual gathering of Chinese officials and representatives of the thirty-three Community of Latin American and Caribbean States member countries. The summit also saw Xi and Colombian President Gustavo Petro formally agree to Bogotá’s entry into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). These developments come amid growing tensions between the United States and LAC countries over trade and tariffs, and growing concern among US policymakers about Beijing’s influence in the Western Hemisphere. Our experts answer the burning questions about this growing partnership below.

1. Why is Colombia joining the BRI?

Colombia’s decision to join the BRI appears less the result of a strategic foreign policy shift and more a reflection of domestic political needs and improvised diplomacy. In the lead-up to Petro’s visit to Beijing, tensions between him and Foreign Minister Laura Sarabia—particularly over the BRI—exposed the administration’s lack of internal consensus on China policy. Colombia did not have a clear framework for engaging China, and the memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed during the visit reflects that ambiguity.

The MOU itself is broad and general. It outlines cooperation across diverse sectors—connectivity, health, technology, green development, and trade—without tailoring to the specific contours of the Colombia-China relationship. There are no flagship projects or unique priorities; instead, it reads like a catch-all document with aspirational language. This generic approach suggests that Colombia is not yet in the driver’s seat when it comes to shaping its partnership with China. As things stand, China is likely to define future cooperation with Colombia under the BRI framework.

Aligning with the BRI offers Petro a symbolically strong, though substantively vague, diplomatic win amid mounting challenges at home. It also aligns with Petro’s broader ambition to project himself as a regional statesman. His remarks at the China-CELAC Forum were less about concrete proposals and more about positioning himself as a Latin American voice in global affairs.

Yet, this decision carries geopolitical risks. Petro spoke positively of the United States during his speech in Beijing and even called for a CELAC-US summit in an apparent attempt to reassure Washington. This cautious messaging suggests Colombia joined the BRI without preemptively managing the fallout with its principal strategic ally. The lack of a coherent China policy parallels an equally absent US engagement strategy, which is concerning given the potential sensitivities around growing China-Latin America ties, especially under the Trump administration.

Colombia’s entry into the BRI reveals more about its domestic political landscape and reactive foreign policy than any strategic realignment. It remains to be seen whether the country can translate this membership into tangible, sovereign-led development outcomes.

—Parsifal D’Sola is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and the CEO of the Andrés Bello Foundation–China Latin America Research Center in Bogotá.

China is already an important economic partner for Colombia. Economic ties between the two countries have been deepening for the past fifteen years and Petro inherited an economy that was already increasingly interconnected with China’s. While the United States remains the country’s main trading partner, January data showed Chinese products leading over US imports for the month. Ultimately, Colombia does not need to sign on to the BRI to continue deepening its commercial and investment relationship with China. In fact, doing so is a surefire way of losing friends in Washington at a time when the Trump administration is laser-focused on combating Chinese influence in the Western Hemisphere. So this is ultimately about domestic politics. An April survey by the leading pollster Invamer found that 62 percent of Colombians now have a favorable opinion of China, up 12 percent since February. This compares to just 40 percent that have a favorable opinion of the United States.

The MOU is wide-ranging. The focus goes beyond mere infrastructure to include topics such as technological exchange, decarbonization, and reindustrialization—but none of that comes with a clear commitment. Instead, the pillars mirror the main elements of Petro’s National Development Plan, suggesting this is merely a statement of intent from China to continue to play a role in Colombia’s economic development rather than a play to pry Colombia away from Washington’s sphere of influence.

This showcases the challenge that the United States faces in convincing Colombia of the value of US partnership. There was alarm in Washington over the fact that a Chinese firm inked a deal to construct and operate Bogotá’s first metro system. But no US firms placed bids on the metro system project or on any of Colombia’s large infrastructure projects in recent years. If Washington hopes to compete with China in the Western Hemisphere, it will have to credibly demonstrate a willingness to dramatically increase investment in infrastructure and other sectors that are attractive to Colombia and other governments across the region.

—Geoff Ramsey is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Colombia’s announcement to join the BRI came in 2024 after Petro signaled that his administration would further open its markets to China and diversify its international partners to seek greater commercial and investment opportunities. Moreover, Colombia became one of China’s strategic partners during Petro’s 2023 visit to Beijing. In this sense, the official signing of Colombia’s participation during the China-CELAC Summit only reiterated previous plans to expand ties with China. Even before this announcement, Colombia had already welcomed several Chinese investments into the country, including Bogotá’s metro line, by China Harbour Engineering. While this move may raise some concerns over Colombia’s relationship with the United States, it is also a test of how Petro’s administration will balance relations with both Washington and Beijing as US-China tensions escalate.

—Victoria Chonn-Ching is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, where she supports the Center’s China-Latin America work.

While some countries in the region remain cautious in their approach to China to maintain cordial relations with Washington, Colombia is embracing the opportunity to deepen ties with Beijing. Once hailed as a model of US bipartisan support in the hemisphere for its commitment to counterterrorism and anti-narcotics efforts, Colombia is now erratically pivoting under Petro. He has justified this shift by citing the strain placed on the US-Colombia Free Trade Agreement by the Trump administration’s imposition of “reciprocal tariffs.” These tariffs have effectively altered the commercial agreement’s 0 percent tariff baseline, imposing a 10 percent duty on non-mining and energy products. This affects the competitiveness of key Colombian exports to the US including coffee, cut flowers, avocados, mangoes, blueberries, peppers, light manufacturing goods, and apparel. Petro claims that China might now buy all these goods without conditions, but Beijing will not grant this for free.

Petro suggested that the free trade agreement with the United States needs to be renegotiated because it left Colombia with a trade deficit. But Colombia’s trade deficit with China is over thirteen billion US dollars per year, so it is not clear if the accession to the BRI will be an appropriate answer to this populist complaint.

—Enrique Millán-Mejía is a senior fellow for economic development at the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. He previously served as a senior trade and investment diplomat of the government of Colombia to the United States between 2014 and 2021.

2. What signals did we get from the rest of the region about China during the summit?

The latest China-CELAC Forum followed a familiar pattern: strong symbolism, minimal substance. While participation was notable—seventeen foreign ministers and three heads of state attended—the event was more a showcase of diplomatic optics than a venue for concrete policy advancement. Lofty rhetoric dominated public pronouncements, but there was little in the way of actionable deliverables or follow-through mechanisms.

The headline announcement—a $9.2 billion credit line for the region—made waves, but details remain scarce. No specifics were offered regarding how the funds will be distributed, which countries will benefit, or what the timeline looks like. Given China’s track record of making high-profile pledges that don’t always translate into implementation, it’s prudent to temper expectations.

The clearest signals came not from the multilateral setting but from bilateral tracks—especially Brazil and Chile. Both countries sent their presidents accompanied by large, high-level delegations. The presence of Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, alongside nine of his ministers, underscored Brazil’s intent to deepen ties with China through structured, bilateral channels. The contrast with his visits to the United States is stark: all of Lula’s trips to Washington have involved significantly smaller delegations, often limited to a handful of advisers. That disparity speaks volumes about where Brazil sees its strategic priorities.

Chile followed a similar playbook, arriving in Beijing prepared to engage substantively. These engagements signal that China is increasingly prioritizing bilateral diplomacy over regional multilateralism when it comes to tangible cooperation. Countries with a clear agenda and internal coordination—like Brazil and Chile—are well-positioned to benefit.

The forum revealed more about China’s dual-track approach—multilateral symbolism paired with bilateral pragmatism—than about any coordinated regional response to China’s rise.

—Parsifal D’Sola

3. What are the diplomatic implications of the summit for China?

This week’s China-CELAC summit in Beijing underscores China’s expanding ambitions to exert greater influence in Latin America and the Caribbean. What were once isolated engagements with select countries have evolved into a substantive effort to shape economic development, forging geopolitical alliances in some cases and ideological ones in others. This shift is evident in China’s pledge of substantial financial support—$20 billion for infrastructure, $10 billion in concessional loans, and a $5 billion cooperation fund—solidifying China’s increasing role as a development partner in the region.

Initiatives such as the “1+3+6” cooperation framework and Colombia’s decision to join the BRI reflect a broader trend among Latin American countries seeking to diversify their economic partnerships beyond traditional Western allies. Beyond economic cooperation, China is also strengthening collaboration in technology and legal frameworks. Projects like the China-LAC Technology Transfer Center and the China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite program demonstrate Beijing’s intent to integrate the region into its innovation ecosystem. The inaugural China-CELAC Legal Forum further institutionalizes these ties, fostering cooperation in areas such as digital law, finance, and governance.

Diplomatically, China’s growing presence poses a direct challenge to US dominance in the region. China is also leveraging the summit to diplomatically isolate Taiwan by engaging with countries such as Haiti and Saint Lucia—two of Taiwan’s remaining allies—further undermining Taipei’s international recognition.

China is also expanding its soft power through scholarships, training programs, and youth exchanges designed to cultivate relationships with future regional leaders. The summit reflects China’s aim to foster a multipolar global order, employing economic incentives, diplomatic engagement, and cultural diplomacy to establish itself as an indispensable partner to Latin America and the Caribbean.

—Enrique Millán-Mejía

The summit provided new indications that LAC countries must continue to collaborate on economic issues, particularly in the context of a lack of investment in regional infrastructure and ongoing pressure from the United States, which is engaged in a global trade war.

At the opening of the event, Xi emphasized his role as a reliable partner for LAC countries in the face of “geopolitical confrontation” and “protectionism,” a clear criticism of the United States. Xi also proposed initiatives to “build a Sino-Latin American community with a shared future” and pledged $9.2 billion in development credits for the LAC region. The delegations of the thirty-three CELAC countries responded positively, but there are still few details about how and when it will be spent.

But the announcement represents a further development in China’s interest in LAC. The region is a key target for Beijing, which is already the primary trading partner of Brazil, Peru, and Chile. Indeed, trade between China and the LAC countries surpassed $500 billion for the first time last year, a figure forty times higher than at the beginning of the century.

In contrast, despite the commitment of CELAC to regional integration, its members have taken different approaches to Beijing. While Colombia signed an agreement to join the BRI, Brazil has long avoided making such an association despite strengthening Brazil-China ties.

The United States’ more aggressive approach to Latin America has prompted several Latin American and Caribbean countries to seek closer ties with China, a phenomenon that emerged during US President Donald Trump’s first term. However, the practical implications of this enhanced relationship with Beijing over the next few years, and the potential costs for the region, remain uncertain.

—Thayz Guimarães is a visiting fellow for the China in Latin America Program at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and a foreign desk reporter at the Brazilian newspaper O Globo.

4. What are the implications for the United States?

The summit demonstrated China’s aims to strengthen ties and be seen an attractive partner for the region by highlighting its support for multilateralism and opposition to protectionism. For many countries in the region, China has become a key partner, albeit one that is treated with caution and reluctance. Nevertheless, as US-China competition continues, LAC countries may have to face the challenge of balancing the pursuit of their own interests as Washington seeks reengagement with the region and China increases its efforts to present itself as a more reliable partner.

—Victoria Chonn-Ching

As China deepens its ties with LAC countries through trade, it challenges the United States’ historical dominance in the Western Hemisphere. On the diplomatic front, the summit proves China’s ability to present itself as an alternative partner that offers less conditional support compared to the United States, which sometimes links aid to governance reforms or democratic norms. This approach resonates with some leaders, especially in LAC countries that are disenchanted with US foreign policy. For the United States, failure to recalibrate its approach to regional diplomacy risks further alienation and erosion of soft power in its traditional sphere of influence.

The United States faces a strategic imperative to strengthen its alliances in the region. Washington should pursue this through renewed diplomatic efforts, competitive investment initiatives, and cooperative programs that address shared challenges such as renewable energy, illegal migration, and economic inequality.

—Enrique Millán-Mejía

Further reading

Tue, Mar 25, 2025

Dispatch from Hong Kong: The Panama Canal port sale has put Chinese authorities in a bind

New Atlanticist By Josh Lipsky

Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison Holdings’ decision to sell its Panama Canal ports to BlackRock stunned officials in Hong Kong and Beijing.

Mon, Mar 24, 2025

Is China or the US the ‘wolf warrior’ in Latin America now?

New Atlanticist By Caroline Costello

The United States’ harsh rhetoric toward Latin American nations has given China an opportunity to falsely present itself as a more altruistic partner to the region.

Thu, Nov 14, 2024

China’s advances in Latin America should concern Trump

Inflection Points Today By Frederick Kempe

As Chinese leader Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden visit Peru and Brazil this week, the contrast between the US and Chinese approaches to the region is stark.

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping and Colombian President Gustavo in Beijing, China, on May 14, 2025. Juan Diego Cano/Pool/Latin America News Agency via Reuters Connect.