The visits to Washington this week by Europe’s two top leaders—French President Emanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel—underscore the dramatic changes within Europe and in the transatlantic relationship over the past year.

The visits to Washington this week by Europe’s two top leaders—French President Emanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel—underscore the dramatic changes within Europe and in the transatlantic relationship over the past year.

France has emerged as arguably the European Union’s most influential nation today, and certainly as Washington’s preferred partner. In this, France replaces Germany, which had a privileged role with former US President Barack Obama and his predecessors, and a dominant role within the European Union (EU).

The reasons for this role reversal, which may prove to be transitory, are rooted in recent developments in France and Germany and in the divergent paths taken by each leader in their relationships with the United States, which under President Donald J. Trump has mounted a serious challenge to the postwar world order.

The respective visits also reflected the agendas of each leader and the state of their ties to the US president. Macron received the Trump administration’s first state visit, while Merkel, in sharp contrast, got a working meeting of less than three hours.

Though both Europeans share the same overall agenda, Merkel was primarily interested in preventing a transatlantic trade war, especially given her country’s large export sector, while Macron attempted to shift Trump’s thinking on a range of issues from Syria and climate change to the Iran nuclear deal and multilateralism.

Merkel’s standing in Germany and authority within Europe has been eroded following protracted negotiations to form a new coalition government in the wake of last September’s election. In that election, the far-right populist AfD (Alternative for Germany) party saw dramatic gains, and Merkel was left with to share power with the SPD (Social Democratic Party).

Macron, on the other hand, following his surprise election last May, quickly consolidated his domestic political power in a system that already makes him one of the world’s strongest democratic executives. His youthfulness, dynamism, and charm have helped, too.

A year ago, no one could have expected that Merkel, who just began her fourth term and whose nation has long been Europe’s economic motor and political powerhouse, would be overshadowed by a forty-year-old former banker with no prior political experience.

Within Europe, Macron has promoted a broad reform agenda, including greater integration of the eurozone and the creation of a rapid response force. He has encountered considerable resistance in Germany and other countries to these proposals. His defense proposals will require countries like Germany to follow France in upping their outlays as well as better defense industrial cooperation.

During her visit to Washington, Merkel stressed the progress Germany has made on defense. Germany currently spends 1.2 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, less than the 2 percent target agreed to by NATO member states. Merkel announced on April 27 that this would be upped to 1.3 percent in 2019.

As concerns have mounted in Europe about Trump’s indifference or opposition to the values and norms that have defined the West and the liberal international order for decades, many wondered who, if anyone, now leads the West.

Some analysts suggested that role fell to Merkel. However, as longtime European expert and Atlantic Council nonresident senior fellow Stanley Sloan suggested last June, Germany clearly lacks the military power to play that role.

Into this vacuum stepped the ambitious young French leader, who has emerged as the champion of the liberal world order against the challenges of illiberalism and populism. This was reflected in his April 17 speech to the European Parliament in Brussels that came soon after the re-election of populist Viktor Orban as prime minister of Hungary and his April 25 address to a joint meeting of the US Congress in Washington.

After Macron’s speech to Congress, Steven Schmidt, who ran Republican Sen. John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign, tweeted: “[I]t is perfectly clear Macron is the leader of the free world. Trump vacated the job.”

However, Sloan tweeted: “[Macron] certainly stands out as the leading spokesman for Western values. Whether anyone can ‘lead the West’ other than the United States is an open question, but it certainly cannot and will not be led by [Trump].”

Macron and Merkel have taken two different approaches to Trump. While Macron has sought to emphasize areas of agreement with Trump while speaking frankly in private, Merkel has offered the US president support conditioned on his respect for traditional liberal values.

This has been apparent in the different relationships each European leader has with Trump—a contrast evident in the body language between the leaders.

While Macron’s state visit included an intimate dinner in Mount Vernon, a state dinner at the White House, a night at the opera, and an address before the US Congress, Merkel got a working lunch and a press conference.

Macon and Trump repeatedly held each other’s hands, exchanged air kisses, and slapped each other on the back, while Merkel and Trump maintained a more business-like demeanor. However, compared to their frosty meeting a year ago, the US and German leaders had a much more cordial meeting this time.

Macron used his rapport with Trump to press the US president not to abandon the Iran nuclear deal and the postwar liberal international order.

Macron shifted his public stance in his address to Congress in which he made a more direct and pointed critique of the US president’s worldview and policies. He spoke strongly in defense of multilateralism and once again said that climate change must be addressed because “there is no Planet B.” He also said that trade wars and “massive deregulation and extreme nationalism” were not the answers to problems in international trade.

While the French president had some success in persuading Trump of the merits of a side deal to the Iran nuclear accord on ballistic missiles and Iran’s aggressive regional behavior, he told reporters he feared Trump was likely to end US participation in the deal.

In a joint press conference at the White House on April 27, Merkel called the Iran deal “anything but perfect,” and said the country’s regional ambitions must be curbed. She voiced openness to possible bilateral trade deals, thanked Trump for his work on North Korea, and repeated her view that “Germany and Europe must take their destiny in their own hands and not rely on the United States” as much as in the past.

It remains to be seen how effective Macron will ultimately be in pursuing his agenda, and whether his country’s close ties with the United States will outlast the time in office of the current presidents of the two nations.

Germany’s power within the EU, including its influence over other EU members, should never be underestimated, nor should Merkel. The next German chancellor and US president may form a deeper bond than Merkel did with Trump.

Louis Golino is an independent analyst covering Europe, US foreign policy, and transatlantic affairs. He was formerly at the Library of Congress’ Congressional Research Service where he worked on NATO and EU issues.

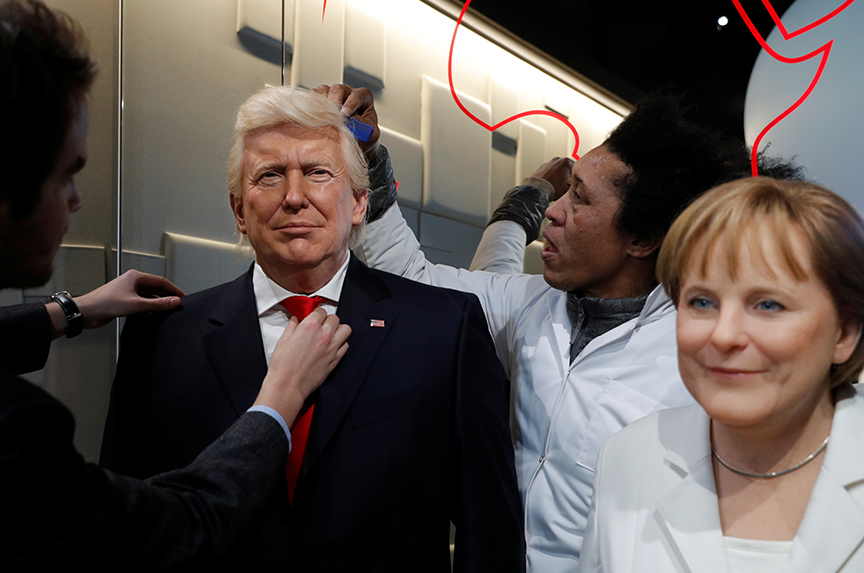

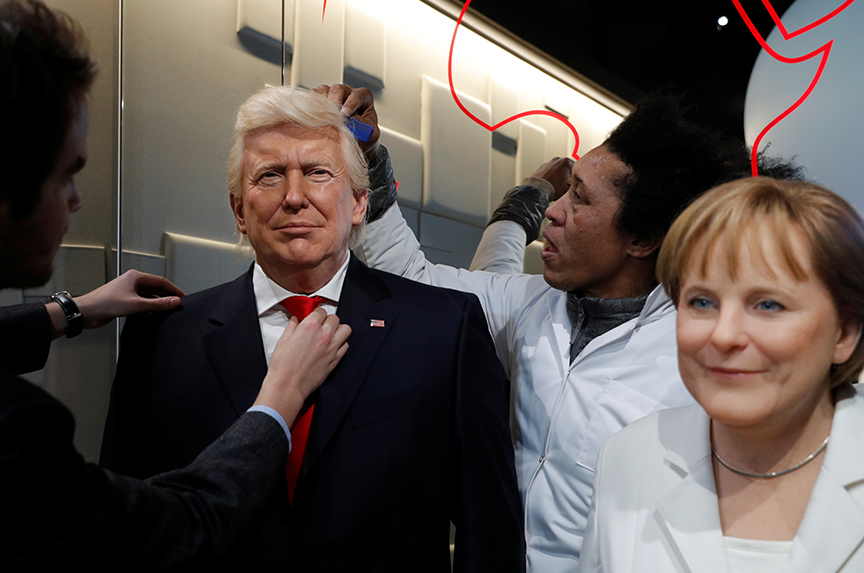

Image: Technicians adjusted a waxwork of then US President-elect Donald J. Trump, which was presented next to a waxwork of German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the Musee Grevin in Paris on January 19. Trump will meet Merkel in Washington on March 17. (Reuters/Philippe Wojazer)