On October 20, 2011, the death of Libya’s longtime dictator Moammar Gadhafi at the hands of rebels in his hometown of Sirte put an end to the revolution that erupted in February of that year, and ushered in a new political and military elite. This new leadership was supposed to guide Libya through a transitional period that would lead to the establishment of a democratic republic. That is far from being the case.

The official narrative saw the Libyan people rising up against the oppressive and corrupt Gadhafi regime and, after a long fight, prevailing over the dictator’s forces, constituted mostly of African mercenaries.

Over time, however, another more correct and realistic narrative emerged: this was not a revolution of a people against a dictator and his mercenaries. Gadhafi enjoyed relatively widespread support in Libya. What was sparked in the spring of 2011 was not a revolution, but rather a revolt of one section of society against another, a detail that transformed the “revolution” into a “civil war.” This civil war did not end with Gadhafi’s death; it continues to this day albeit in a different form.

Many sympathizers of the Gadhafi regime sought refuge in Libya’s neighborhood from where they plotted their return. They have become a force that neither the international community, represented by the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Libya, Ghassan Salamé, nor the new Libyan authorities can ignore.

On the seventh anniversary of Gadhafi’s death, it is important to assess his legacy and the opinion that a majority of Libyans have of his regime. There is no doubt that the governments that succeeded the National Transitional Council—Libya’s de facto government for a period during and after the revolution—have not done a good job of moving Libya toward becoming a stable democracy.

The polarization of the political and military forces coupled with the fragmentation of authority and the inability of the various governments to restore security, restart the economy, and provide basic services have exacted a heavy toll on Libyans. It is now common to hear in the streets of the capital Tripoli and other Libyan cities the wistful sentiment: “I wish we could go back to the golden period of Gadhafi’s rule.”

Nostalgia for the past is not an exclusive domain of Libyans. The same phenomenon occurs every time a revolution or a revolt has brought about a change of a long-entrenched system and the elite that represent it. Nevertheless, it is a sign of discomfort with the current situation in Libya that the country’s new political class should neither ignore nor underestimate.

Libyans’ nostalgia for the past is not a revalidation of Gadhafi and what he meant for Libya. There is no sign of such a process occurring at least in the public sphere. There was wide consensus on the positions Gadhafi took against neighbors’ attempts to infringe on Libya’s sovereignty and his anti-colonial policies in Africa and elsewhere. It is true that Gadhafi was not a positive force when it came to creating a cohesive national identity or building strong state institutions, but during his forty-two-year reign Libyans came to know one another, old frontiers were removed, differences were overcome, and ultimately a sense of pride in identifying with a Libyan community rather than a local one prevailed. This fact should not be overlooked. If correctly revived it could help heal many old and new wounds.

It is also time to challenge the narrative that Gadhafi’s Libya was a state completely deprived of institutions. Granted, Libya under Gadhafi was largely a one-man show, but not completely so. There were bureaucracies that worked under laws and regulations such as ministries, city councils; regulatory agencies such as the audit bureau and the central bank; security sector agencies, and so on.

It is not by accident that two of the most competent members of the government in Tripoli today—Minister of Foreign Affairs Mohamed Syala and Minister of Planning Taher Jehemi—served in the Gadhafi administration. The same is true in many other cases throughout the entire state structure. There is no way for Libya to be viable as a state and build new, stronger, and more legitimate institutions without at least to some extent resorting to the expertise of old cadres of state functionaries, despite the risks that this may comport in terms of loyalty to the new system and allegiance to the new leadership.

There is, right now in Libya, a return within the country of sympathizers of Gadhafi’s Jamahiriyya. In most cases, this sympathy is a form of resentment for the marginalization of constituents of the old regime by the revolutionary elites more than a real allegiance to the old form of government.

Gadhafi and Gadhafism have become a symbol for the dissatisfaction with the new situation, not an assertion of the superiority of the old regime. Declarations and statements by former Gadhafi loyalists expressly state their allegiance to a pluralistic and constitutional system not to a return to the Jamahiriyya or dictatorial exercise of power.

There is a need in Libya to study the past and interpret it with realism and rationality rather than reimagine it as a mythical era where everything was better. This exercise will go far in reconciling the population with its history and with its search for a political system rooted in the identity and aspirations of all Libyans, not just a few of them.

Gadhafi is dead and so is his regime, but that doesn’t mean we should ignore the positive elements of the past that can contribute to the creation of a new, more inclusive Libya.

Karim Mezran is a senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. Follow him on Twitter @MezranK.

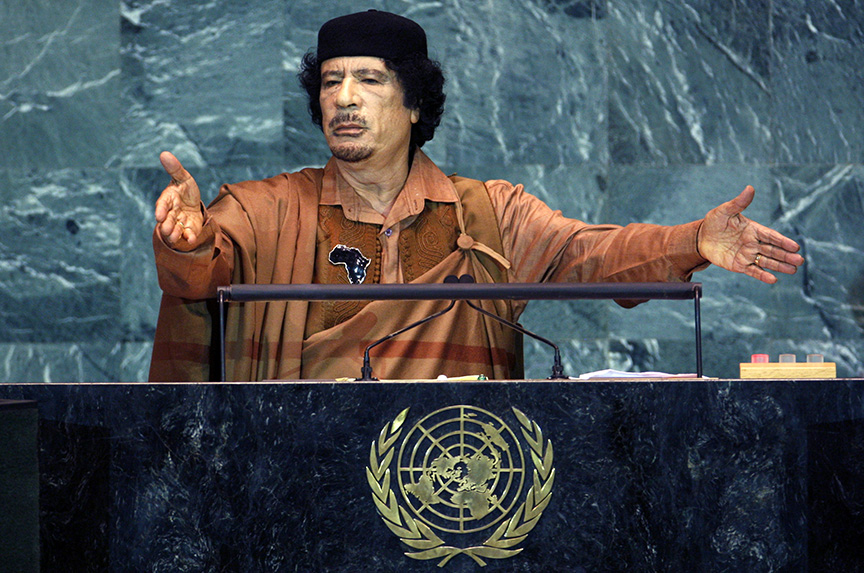

Image: Moammar Gadhafi addressed the 64th United Nations General Assembly in New York on September 23, 2009. The Libyan leader was killed by rebels in his hometown of Sirte, Libya, on October 20, 2011. (Reuters/Mike Segar)