On June 26, just before Greece’s referendum, and on July 14, one day after the so-called agreement between the Greek government and the creditors (the International Monetary Fund, the European Union, the European Central Bank), the IMF unusually made public a short but crucial document in any negotiation over a financial aid package: the debt sustainability analysis (DSA).

We want to answer four questions:

- Why is the announcement unusual?

- Why is debt sustainability so relevant to the IMF?

- How did debt sustainability deteriorate over time?

- What can be done about it?

Why is the announcement unusual?

The DSA is an integral part of any assessment of an IMF program. It is an annex in the Article IV report for each and every country that is a member of the IMF or is presented at the board for consideration as an annex of the quarterly review in the case of a country under a program. It never comes as a separate document and it never becomes public without the board’s approval.

This is the first time that a DSA comes as a standalone document, which shows the IMF’s intention to make public its dissent over any agreement that does not contemplate a deep debt restructuring. In this case, the IMF wants to press not just the country concerned, but mainly its creditors—i.e. the European countries and the European institutions—to reach a deal that can give some hope for Greece to regain market access.

Why is debt sustainability so relevant to the IMF?

In order to lend money to a country, this analysis must show that the country is sustainable over the medium term (three to five years) with “high probability.”. This means that there is a high probability for the IMF to get the money back since the country will regain market access and will be able to finance its debt and repay the official creditor. When the DSA shows sustainability with high probability, then IMF staff can recommend that the board conclude the review and make the disbursement.

In the case of Greece, even at the very beginning of the bailout program there was clarity that the debt was not sustainable with high probability and therefore a so-called “systemic clause” was invoked that would have allowed the IMF to start a program for Greece and lend money. In brief, there was a systemic risk of contagion given the fact that Greece was (and still is!) in a currency union and that other countries in the same union were under heavy market pressure.

This was quite controversial because it was seen by some IMF member states—mainly Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, the BRICS—as a violation of even-handedness. In several cases, the IMF asked for a debt restructuring before starting a financial assistance program, while it did not do the same for Greece. To make a recent comparison, debt restructuring was a condition for the completion of the first review in the new program for Ukraine.

However, even under the “systemic clause,” the country cannot be “highly unsustainable” as it is shown now in the latest analysis released on July 14, because otherwise the risk that the IMF will lose its money becomes too big. At the end of the day, the IMF is like a bank, with a limited and special group of clients—the 188 member states—who go to this bank only when anybody else (the market) decides it is too risky to lend money.

It is a risky business and the risks must be mitigated in some way. The IMF has three tools: put conditionality on any loan, assess the sustainability of the debt under program conditions, and the preferred creditor status. The third option is a “gentlemen’s agreement” among member states because it is not written anywhere that the IMF must be paid before any other creditor. But thanks to this status the IMF was able in the past to take relevant risks and activate financial assistance programs to countries with no market access.

The IMF does not want to put at risk this preferred creditor status and therefore insists that European official creditors do their job and allow a debt restructuring. It also wants to reaffirm that it is a rules-based institution and cannot have special treatment for one of its members. And it considers this as the only way to have its credit repaid.

And most likely, there is also a fourth reason: it considers a debt restructuring the only hope for Greece.

How did debt sustainability deteriorate over time?

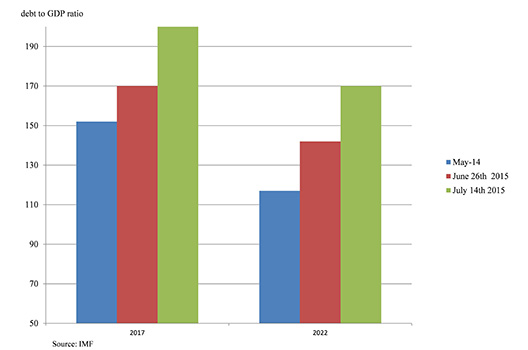

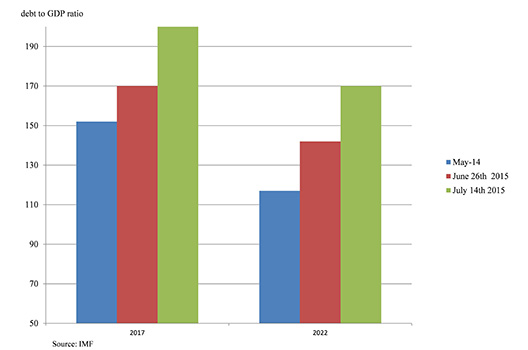

A comparison of the three latest updates of the DSA shows a sharp deterioration of the debt profile. The figure shows the debt to GDP ratio under the three updates for 2017 and 2022. While one year ago the debt to GDP ratio for 2017 was estimated to be slightly above 150 percent, the latest figures show a much higher number, at 200 percent. This is due to a deterioration of growth expectations as well as a much lower expected primary surplus. Interestingly, assuming the same profile for GDP growth and primary surplus, the debt to GDP ratio projected for 2017 deteriorated by 30 percent (€60 billion) in the last two weeks.

Quite obviously, the IMF stated on July 14 that “Greece’s public debt has become highly unsustainable.”

What can be done about this?

The IMF analysis is still based on the unrealistic hypothesis of high primary surpluses for a very long period of time. If the projections take reality into account, it is clear that there is no alternative but a debt restructuring.

This is unfortunate because European taxpayers will lose money, the IMF will likely have arrears with Greece for several years ahead, and Greece itself will suffer austerity in exchange for debt restructuring. However, it will finally make clear that five years of assistance from international financial institutions did not work (no matter who is to blame).

But at this stage it simply does not make sense to avoid the problem. Likely, a sort of debt re-profiling (longer grace periods and longer amortization) will materialize in the bailout program, if there is one. Most probable, it will be a political commitment to be included in the first Memorandum of Understanding, which will become an integral part of the program after the first review. Only if Europe presents a credible re-profiling plan will the IMF reengage with Greece and agree to be part of a financial package. Until then, it will likely provide technical assistance and be part of the troika but without financial disbursement.

Another possibility is that a debt re-profiling will be considered insufficient to ensure sustainability. In that case the IMF will condition a third bailout on a proper haircut. Is this something Germany will accept?

Andrea Montanino is the Director of the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program.