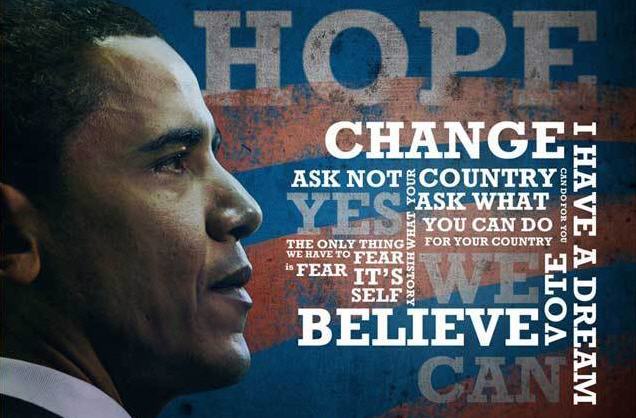

President Obama ran his hugely successful 2008 election campaign on the themes of hope and change. Unfortunately, he is also running the Libya war based on the same themes with far less success. The coalition strategy is to hope that escalating airstrikes will fracture Colonel Gaddafi’s inner circle and give the ragtag group of rebels enough momentum to bring about the fall of the ruling regime in Libya.

Hope was a great campaign slogan, but it is unlikely to be a successful military strategy. Worse still, the failure to present a more credible strategy for achieving an endgame in Libya has opened the doors for more hawkish and dangerous alternatives.

Libya is settling into a discouraging stalemate. The rebels are disorganized at best and incompetent at worst. Absent major coalition airstrikes that go above and beyond the interpretation of UN Resolution 1973, the rebels are unable to exert any pressure on Gaddafi strongholds of Sirte or Tripoli. More than surgical airstrikes will be required to dethrone the self-proclaimed King of Kings. That’s where hope comes into play.

With the weakness of the rebels obvious for all to see, the Obama administration has put the greatest stock in hoping that betrayal from Gaddafi’s inner circle will bring down the regime. Even the hard-headed Defense Secretary Robert Gates, wisely skeptical of this intervention in the first place, put forward the administration’s wistful strategy in his whirlwind tour of the Sunday morning talk shows saying to Bob Shieffer of CBS, “The military attacks began essentially a week ago, last Saturday night. And– and don’t underestimate the potential for elements of the regime themselves to crack.” The defection of longtime Gaddafi confidante and Libyan Foreign Minister Mussa Kussa will no doubt raise hopes that the mounting pressure of coalition airstrikes will cause further defections.

Unfortunately, the core of Gaddafi’s regime and fighting power is led by Colonel’s sons and manned by their tribesmen, who are unlikely to betray their own. And Tripoli and Sirte are likely to prove much harder to capture than towns of more questionable devotion to the regime in the east. This means President Obama and the allies must hope for luck.

The president and his team understand that a stalemate would fracture the NATO Alliance, weaken Arab and broader international support for military operations, dissatisfy the American electorate, and leave a dangerous and vengeful dictator in charge of at least part of his country and a still formidable cache of weapons and gold bullion.

The president’s incoherent strategy for bridging the coalition’s limited military means to the ambitious political objectives of regime change has given more hawkish voices room to fill the void with dangerous ideas. The neoconservatives, back earlier than expected from their post-Iraq policy exile, helped bait the President into this intervention in the first place by teaming up with human rights crusaders and Clintonistas, guilt-ridden by their failure to intervene in Rwanda in the 1990s. With the president now sucked into the conflict without a credible end-game, the hawks have the political space to advocate ever more aggressive military actions to bring about the fall of the Gaddafi regime.

The Washington debate now revolves around arming the rebels, whom NATO Commander Admiral Jim Stavridis admits may have ties to Islamic extremists. You might imagine that after ten years of fighting Taliban militants in Afghanistan, some of whom were armed with weapons sent by the CIA during America’s clandestine war against the Soviets in the 1980s, that we would know better than to arm Muslim insurgents yet again. Or that there would be some recognition that imported arms will do more harm than good without training and military advisors to help coordinate the actions and activities of the rebels. Or that after the Iraq experience we might not try to so hastily overthrow a long-standing iron-fisted dictator without a better plan and vision for what would follow.

But these careless ideas will rise to the fore as long as the President is unable to articulate a strategy other than hope to bring about the fall of the Gaddafi regime. NATO can likely maintain its sustained bombing campaign for one to two more weeks before public opinion in member states and the broader international community turns. This gives Turkey and others a bit more time to attempt to negotiate Gaddafi’s departure and offers the allies a bit more time to pressure the regime in hopes of its collapse.

If all else fails and Gaddafi is able to weather the storm, the international community will have to contain a degraded and weakened Muammar al Gaddafi with what is likely to be a partitioned state. This would be an embarrassing climbdown, but it need not be the end of the world. Even that very unsatisfactory outcome would be better than the United States having to assume ownership of building a post-Gaddafi Libya. And it would enable the administration focus on America’s real strategic interests: Egypt, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia.

Starry-eyed idealism got the United States and its allies into this conflict. Unless luck intervenes and hope prevails, only hard-headed realism will get us out of it. Cross your fingers and hope for the best.

Jeff Lightfoot is an Associate Director of the Atlantic Council’s International Security Program.

Image: obama-hope-change-wordcloud.jpg