Our current age of “automation anxiety” is nothing new. Writing in 1930, John Maynard Keynes was concerned with the onset of “technological unemployment” and the “temporary phase of maladjustment” which would ensue. In 1964, US President Lyndon Baines Johnson commissioned a study on “technology, automation, and economic progress” which outlined recourse for the government to act as “employer of last resort (EOLR).” More than half a century later, economists, executives, and policy makers are consumed with “brilliant technologies” and the impact on employment in the “second machine age.”

It is the pace of change happening now—the onset of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and robotics—unfolding contemporaneously with large social undercurrents of inequality, populist movements, and an increase of protectionism that has induced an almost pervasive sense of distress in advanced economies today.

Automation and advancing technology have contributed to a U-shaped curve of employment in the United States and other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies, with a hollowing out of the middle-wage industrial and manufacturing jobs and growth in “new economy” jobs—such as personal services—on the one end of the spectrum, and business and professional services at the other end. The corresponding wage polarization alongside these labor market developments has almost certainly contributed to the rise of populism and the return of geopolitics. But the important thing is not to give way to despair. Solutions can be enacted by both governments and the private sector, which may even spur opportunities for long-term investing. These solutions are not only applicable in advanced economies, but also in still-developing societies such as such as Brazil and China as they transition from old to new economic growth.

What are the facts?

The latest waves in rapidly advancing technology and robotics have unfolded beneath a wider umbrella of long-term shifts in patterns of demand. In advanced societies, we have evolved from agrarian, to heavy industrial manufacturing, to services-based employment. And in an age in which investors speculate about the “death of retail,” personal expenditures are often directed toward leisure, health, and personal services, rather than the acquisition of goods. Beneath this umbrella of secular change, significant advancements in technology in the manufacturing and industrial sectors have led to “skill-biased technical change (SBTC).” In countries such as the United States, as improvements in technology have replaced task-intensive, routine jobs in the middle of the employment spectrum, a U-shaped employment curve has emerged, with a polarization of jobs to non-routine, manual services jobs at one end of the curve, and non-routine, cognitive jobs (white collar) at the other. Although there are other contributing factors to the “hollowing out” of middle-skill and middle-wage jobs in the United States—trade shocks from greater import competition from China, the globalization of labor markets, and the decline in private sector unions, for example—our focus is on what Keynes called “technological unemployment.”

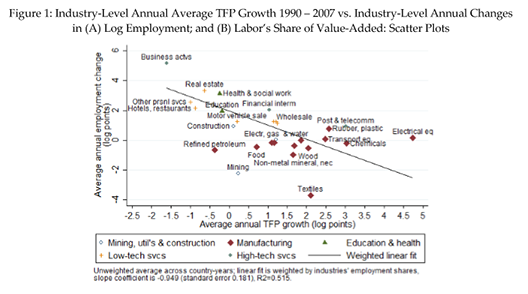

Over the last three decades, the United States has witnessed robust job growth in business services, personal services, education and healthcare, real estate, and hospitality and leisure, with losses in old economy sectors, such as mining [Figure 1]. Alongside these shifts in employment, wages have polarized, with the highest wages in the white-collar business and professional sector, and lower wages for personal, leisure, and healthcare services. It is likely that real wages in services have been further compressed by an influx of workers phased out of the old economy, as middle-skill workers—particularly those without a college degree—are more likely to migrate to non-routine manual jobs than they are to non-routine, cognitive jobs which may require postgraduate degrees.

Figure 1:

Source: David Autor and Anna Salomons

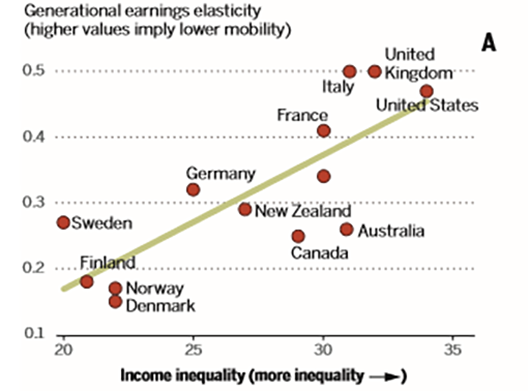

In a worrisome development for global financial markets and long-term economic growth, wage inequality in the United States corresponds with a lack of intergenerational mobility. Indeed, contrary to popular belief about the ease of achieving the “American dream,” “the US has both the lowest mobility and the highest inequality among all wealthy democratic countries” among a comparable set of OECD countries. As we can see in Figure 2, Italy and the United Kingdom are not far behind in ranking for the lowest mobility and highest inequality.

Figure 2:

Source: David Autor

These three countries—the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy—also happen to be the epicenter of populist politics today, which one could argue set into motion a negative feedback loop. An increase in protectionism, volatility in financial markets, and uncertainty in immigration policy can have a paralyzing effect on business and companies’ capital spending plans. And in countries such as Italy and the UK, populist movements may even increase the debt-servicing costs, as worried investors dump sovereign bonds, potentially stymying public spending plans.

What are the solutions?

As we consider both sides of the U-shaped employment spectrum, there are certain jobs which are unlikely to be threatened by automation. In the personal services side, jobs which require visual recognition and interpersonal interaction, such as home healthcare, nurse-care practitioners, security, building maintenance, food preparation, and hairdressing are unlikely to be replaced by a robot. At the high-skill end of the spectrum, business services that prioritize human relationships, flexibility, creativity, problem-solving capabilities, and intuition are unlikely to be replaced by machines.

One can take this a step further: with the automation of some functions of the business world, such as passive index investing, banking, and machine-informed hedge funds, a higher skill premium may be placed on these interpersonal and creative capabilities, which may require different continuing educational and training requirements than traditional technically-focused degrees.

If we recognize that these long-term employment shifts, and corresponding wage inequality and lack of mobility, are long-term problems, there are three solutions which can be enacted by policy makers, companies, and perhaps by investors. These are:

Education: Vocational training is paramount. It can be argued that the United States needs a rapid revolution in tertiary education and “learning for working” for workers to be able learn skills as the “new artisans” in growing sectors. Germany is the exemplar here. Perhaps governments could incentivize companies to grow apprenticeship and training programs with favorable tax deductions. Additionally, by contributing to sustainable employment and reducing wage inequality, companies could clearly meet the “social” criteria of social impact investing; that is, the “s” part of ESG (environmental social governance) benchmarking, becoming increasingly important for global companies and investors.

Job creation: With these long-term changes in mind, governments could generate jobs in thriving sectors such as infrastructure, smart cities, transport, construction and maintenance of affordable housing, green and clean tech, integrative healthcare, and preventive medicine. In such a way, the government’s acting as an EOLR would yield benefits for the taxpayers paying for these projects, whether it was more green space in an urban center, better roads, improvements in healthcare, or better air quality. And research and development can be directed toward dynamic sectors, with goods and services geared to export to growing markets.

Wage subsidies – reinstating the dignity of work: With the hollowing out of manufacturing jobs, wages in the personal services side of the U-shaped curve may be compressed with an influx of new workers (particularly in a scenario in which vocational education helped them to secure these new jobs). Governments could supplement wages in the private sector in some of these growing service industries. Unlike a cash handout or universal basic income (UBI), wage subsidies would help to reinstate the dignity of work. It would be a move from entitlement to empowerment, in supplementing income derived from work.

The supplements may not need to be long-term; with the growth in wages at the high-skill end of the employment spectrum, workers tend to spend more of their disposable income on personal services, leisure, and hospitality, perhaps spurring greater demand in the sub-sector over time.

Conclusion

Looking forward, we are unlikely to roll back the tide of technological advancement, automation, and robotics. As China advances with its Made in China 2025 vision, and countries from Israel to Singapore solidify their positions as AI hubs, it is unlikely that a postmodern Luddite movement will emerge. But the long-term changes which have unfolded over the last few decades—job and wage polarization, and lack of intergenerational mobility—have led to waves of angst, dissatisfaction, insecurity, and distrust by voting publics in many advanced economies. Protectionist cries have spilled over into financial markets, contributing to an uncertain environment in which to make business decisions, and to invest.

The potential solutions—a proliferation of vocational training, job creation in growing sectors, and wage supplements—require long-term thinking, direction, and patience in implementation. The move from entitlement to empowerment necessitates a different kind of communication from governments to their people, and potentially from companies to their shareholders. But by contributing to sustainable employment, and reinstating the dignity of work, stakeholders can do their part in transforming the future of work, creating upside potential, rather than remaining paralyzed in fear.

Dr. Alexis Crow is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program.

Image: A nurse checks the blood pressure of John Rodriguez at the San Rafael nursing home in Arecibo, Puerto Rico February 14, 2018. Picture taken February 14, 2018. (REUTERS/Alvin Baez)