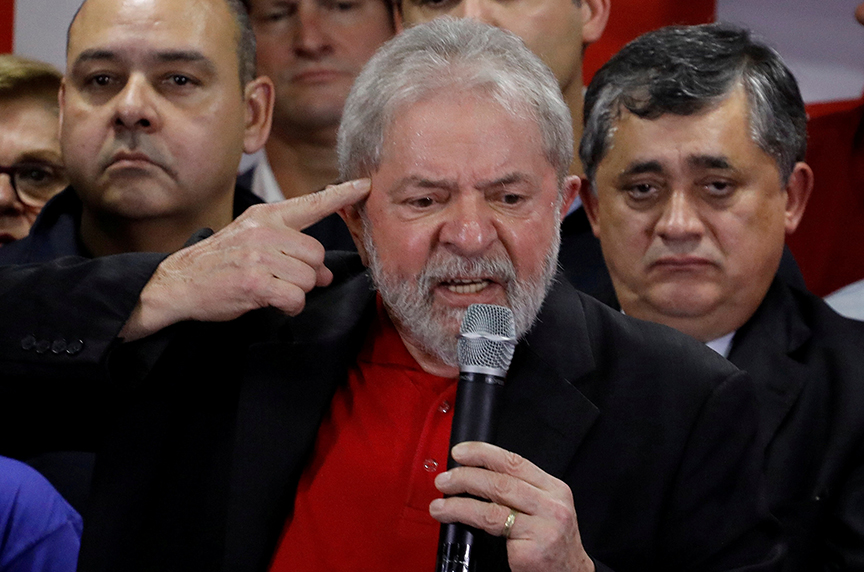

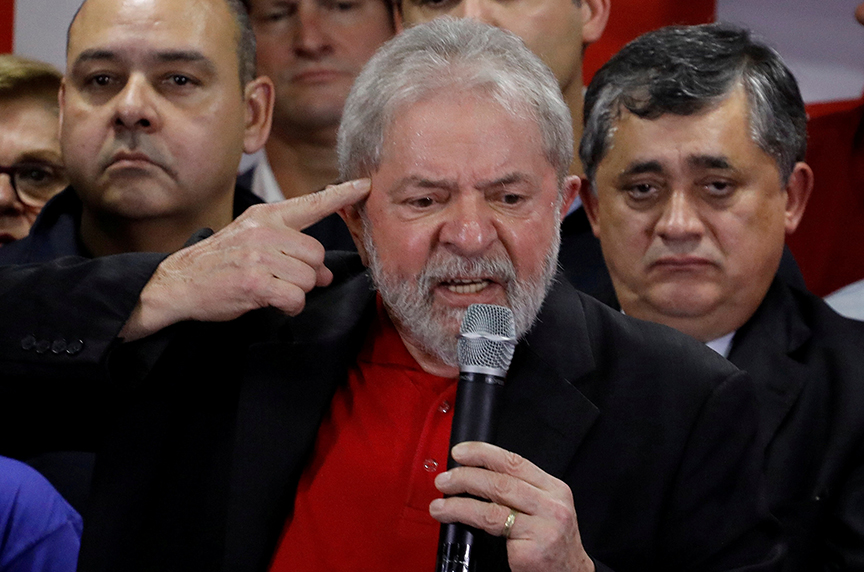

Since 2015, Brazilians have seen former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s name in the headlines, and not for the reasons that led him to be considered one of the most popular world leaders from 2003 to 2011. Over the past two years, Lula, as Brazilians call him, has gotten more entangled in the web of corruption woven around the country. That web finally tightened its hold on the former president on July 12, when he was sentenced to nine-and-a half years in prison for corruption and money laundering. The sentence, regardless of the result of impending appeals, has already changed the image of yet another of Brazil’s elite untouchables, a man who for many represents Brazil’s booming years.

Since 2015, Brazilians have seen former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s name in the headlines, and not for the reasons that led him to be considered one of the most popular world leaders from 2003 to 2011. Over the past two years, Lula, as Brazilians call him, has gotten more entangled in the web of corruption woven around the country. That web finally tightened its hold on the former president on July 12, when he was sentenced to nine-and-a half years in prison for corruption and money laundering. The sentence, regardless of the result of impending appeals, has already changed the image of yet another of Brazil’s elite untouchables, a man who for many represents Brazil’s booming years.

But one or two arrests will not transform Brazil. As the fight against corruption continues, deeper legislative and judicial reforms must follow.

In Lula’s case, the conviction is only a single step forward. In what was the first of potentially five trials, Lula was convicted of accepting $1.2 million—which he applied to the purchase and renovation of a luxury beach apartment—from engineering company OAS SA. In exchange, prosecutors say Lula helped OAS acquire contracts with the state-run oil corporation Petrobras. But Lula’s July 12 sentencing does not mean he’ll be arrested. That will only happen if his conviction is upheld by the 4th Federal Regional Court, to which he will appeal. A final decision could be made before or after the 2018 elections.

Though a hugely symbolic and, one could say, hopeful move in Brazil’s fight against corruption, not all Brazilians have faith that Lula will serve his sentence. Meanwhile, Brazilians, desperate to enact change, have few good options in the 2018 presidential elections.

Lula, tarnished but undeterred by his sentencing, announced on July 13 his intent to run for the presidency in 2018. Marina Silva, the evangelical candidate from the green party; Jair Bolsonaro, a controversial former army captain who has expressed nostalgia for the repressive military regime; and São Paulo Mayor João Doria, a millionaire media mogul and former host of Brazil’s The Apprentice, are leading the pack. All are perceived as problematic by many Brazilians.

The problem, however, goes deeper than a lack of viable candidates. Brazil’s democracy is only twenty-eight years old. It is clear both the legislative and perhaps even the much-celebrated judiciary are in need of reform.

The legislature has its problems. Congress oftentimes approves laws that benefit its own members, and quid pro quo is a common way of doing business. This is most evident in the case of President Michel Temer. The Chamber of Deputies was asked to approve a fresh indictment of corruption and money laundering before Temer could be tried by the supreme court (a privilege of sitting politicians in Brazil). The president and his supporters in Congress have negotiated, they have made agreements, and they have promised funds for deputies’ electoral bases. The result? Temer may receive the votes he needs to sidestep a supreme court investigation and trial.

The judicial system has undoubtedly come a long way over the past few years, but things are not yet perfect. Judge Sérgio Moro, who convicted Lula, arrests one person, and the supreme court releases him or her days later. To this day, many Brazilians know that despite an arrest, no real outcomes may occur. The judiciary must assure that investigations are transparent and that they happen out in the open, and not in political back rooms. The foro privilegiado in Brazil, the mechanism that stipulates those in certain positions of power will be tried by higher courts, is also in need of reform, as these trials can take years or decades to be finalized. Oftentimes, even after judgments have been passed, sentences fail to be implemented. Reforms must go through Congress, and therein lies the problem since many lawmakers are themselves under investigation. Something must change.

As the fight against corruption evolves, Brazil must not overlook the need to push for deeper reforms in the system. Even as one of Brazil’s biggest political icons is held accountable, politicians, the judiciary, and the people must work for reforms that will rebuild a Brazil we can be proud of.

Roberta Braga is a program assistant in the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. You can follow her on Twitter @RobertaSBraga.

Image: President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s attended a news conference after being convicted on corruption charges in São Paulo, Brazil, on July 13. (Reuters/Nacho Doce)