Click on the banner above to explore the Tiger Project.

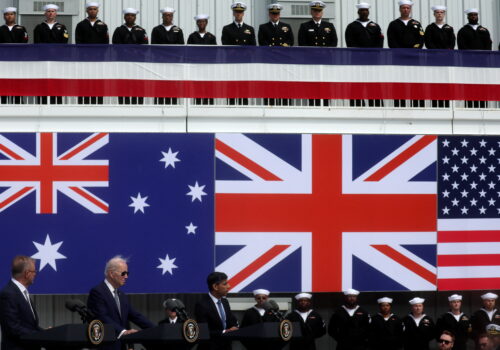

This week, Australian and US forces began Talisman Sabre, a major biennial military exercise that sends a powerful message of the two countries’ resolute bilateral ties and joint capabilities. This year’s iteration is being described as the “largest and most sophisticated war fighting exercise ever conducted in Australia,” involving some 35,000 personnel. The successful completion of this major, three-week exercise will hopefully alleviate some of the anxiety that has built up following the US Department of Defense’s recent decision to review the defense industry pact among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, known as AUKUS.

Much of this anxiety was misplaced in the first place. The US review is not the alliance-busting event that some have portrayed it as. Far from it. It is reasonable and expected that a new US administration would review such an agreement, and it is something that new governments in both the United Kingdom and Australia have also completed. Moreover, the review of AUKUS should be understood as just one part of a larger US effort to accelerate and refine defense industry cooperation to meet shared security goals in the Indo-Pacific.

What else is included in this larger US effort? In a speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore in May, for example, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth announced the first tranche of Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience (PIPIR) projects. It was a decisive move toward deepening US-led defense industrial base cooperation—within the administration’s “America first” framework—to counter China’s looming threat. PIPIR and AUKUS, if employed properly, will be powerful tools to achieve the Trump administration’s vision of ensuring US deterrence against aggression in the Indo-Pacific.

AUKUS: The submarines aren’t the only substance

The first problem is that the AUKUS pact is widely misunderstood. It is not a new trilateral “alliance.” AUKUS does not, for instance, involve new commitments on the use of military force. Nor is it a political coalition, like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue made up of Australia, India, Japan and the United States. Further, despite the focus of recent media coverage, AUKUS is not just about a new submarine sales deal that cut France out of selling diesel submarines to Australia. AUKUS has two “pillars,” both of which hold important benefits for the United States and particularly its Indo-Pacific Command.

Pillar I is about developing nuclear-powered, but nonnuclear armed, attack submarine capability operating out of Australia. This has already started, with Australians training on nuclear submarine technology with US and UK counterparts, and with US submarines making more port calls at Perth in Western Australia. The next major milestone will be in 2027, when Submarine Rotational Force-West will be established at Perth, initially with US and UK submarines. Then, in the early 2030s, the United States will sell Australia Virginia-class submarines as an interim measure while Australia develops its own nuclear submarine production capability. By the early 2040s, Australia will be building and operating its own subs of the new SSN-AUKUS class, an Australia-UK-US design.

However, concerns are rising that the US industrial base may not be able to produce enough Virginia-class submarines to provide for both Australian and US requirements for Pillar I. Since 2022, the United States has only been able to produce 1.2 Virginia-class submarines a year. It has not reached the targeted procurement rate of two new submarines per year, much less the 2.33 production rate required to provide submarines to Australia. While the US Congress and the Australian government have directed billions of dollars to defense industrial base investments, reaching this production rate in the next few years is a herculean task. However, in the interim, even if Pillar I only results in US and UK attack submarines operating out of Western Australia—much closer to the key flashpoints of the Taiwan Strait and the West Philippine Sea—then it has had a meaningful impact.

AUKUS Pillar II, meanwhile, is a much broader effort at defense industrial cooperation in a range of important areas. This includes long-range fires, quantum computing, unmanned underwater vehicles, electronic warfare capabilities, and artificial intelligence, pooling the advanced research efforts of all three countries to deliver new capabilities in the short term. These baskets of capability are not as simple and powerfully symbolic as new nuclear subs, but they are very important. In fact, there’s a strong argument that the focus and funds for AUKUS should shift away from the signature submarine programs to build out these new systems right away. Further, unlike Pillar I, Pillar II has a real prospect of including additional regional allies in specific Pillar II projects beyond the original three partners. Unlike AUKUS Pillar I, which has hard production limitations focused on a very expensive platform type with a long production timeline, Pillar II is bearing fruit quickly. One example of an AUKUS Pillar II capability is the imminent deployment of a “trilateral algorithm” to share classified information from P-8 sonobuoys across each country’s systems, increasing the range and maritime domain awareness of allied anti-submarine warfare efforts.

PIPIR: Leveraging regional US partnerships

PIPIR is less prominent than AUKUS, but it is more expansive and may prove to be even more important. Since its founding in May 2024, PIPIR has evolved from an agreed-upon concept to a plan of action in recent weeks. Announced in late May, the first set of marquee projects shows how the United States looks across the region at opportunities to save taxpayer money and improve US sustainment capability. For example, one new project aims to “establish repair capability and capacity for P-8 radar systems in Australia.” The P-8 is a critical aircraft for anti-submarine warfare and for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions. Currently, repair efforts on the radar system are limited to the continental United States. The ability to repair both US and partner P-8 radar systems out of range of most China’s missiles will enhance both deterrence and sustainment capabilities in the event of a conflict.

Another new project involves identifying standards for small unmanned aerial systems and secure supply chains for production. Currently, China controls nearly 90 percent of the commercial drone market, and the Department of Defense’s innovation unit claims that “China could shut [the drone industry] down globally for a year.” Efforts to build ally and partner supply chains are essential for deterrence and lethality. The commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Samuel Paparo, has continued to emphasize the importance of the “Hellscape” concept of massed unmanned systems to fight China. This new PIPIR project will help buttress the Department of Defense’s Replicator Initiative to ensure “Hellscape” is a credible option that is truly free of Chinese components.

Other PIPIR efforts include expanding in-theater ship repair, cooperation with Australia to produce artillery shells and guided missiles, and even coproduction with India on “equipment needed to deter aggression.” Hegseth’s public release of these projects indicates that partners and allies in the region are confident about PIPIR and the United States’ commitment to its success, with likely even more cooperation occurring behind closed doors.

The way forward

Together, PIPIR and AUKUS Pillar II could prove to be vital to deterrence and defense in the Indo-Pacific. While diplomatic messages and military exercises are immediate, visible, and necessary to shore up deterrence in the near term, aligning defense on industrial capabilities to match China’s massive armament program is the more important strategic move for the years ahead. The US Navy has acknowledged that China has 230 times more shipbuilding capacity than the United States. To provide both a qualitative and quantitative response to China’s push to become a “world class” military power, the need for the United States to integrate the industrial capacity and comparative technological advantages of allies and partners in the region has never been greater. Pitting the US defense industry against China’s without the help of Washington’s allies and partners, is a recipe for the failure of deterrence and, perhaps, catastrophic defeat. As US President Donald Trump has put it in the past, “America first does not mean America alone.”

Further defense industrial cooperation and integration can yield immense and local benefits for the US warfighter. However, these benefits must be carefully balanced with the need to ensure that the US government is not replacing US capacity and jobs with foreign ones to cut costs and speed up timelines. The Trump administration’s recently announced review of AUKUS, and its likely already completed review of PIPIR, under an “America first” framework, will be critical to mitigating this risk. A revitalized AUKUS and PIPIR model can create coproduction and cooperative models, allowing the United States to bring its strengths to the table. The better the United States can work with its regional partners on munitions and systems of mutual use, such as addressing the meager supply of 155mm artillery shells, the more effectively Washington can equip its warfighters to deter, and if necessary, win a prolonged war.

As the Trump administration prepares a national security strategy to help restore US greatness, regional defense industrial base partnerships must play a central role in restoring domestic manufacturing and increasing US lethality and deterrence. The early successes of AUKUS Pillar II and the announcement of marquee PIPIR projects have built a solid foundation for what should be an even more ambitious program of integration and cooperation.

Adam Kozloski is a nonresident senior fellow at the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and at the N7 Initiative in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He previously served as an aide in the United States Senate, supporting Armed Services and Foreign Relations Committee members, including as Senator Joni Ernst’s foreign policy advisor.

Markus Garlauskas is the director of the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, leading the Council’s Tiger Project on War and Deterrence in the Indo-Pacific. He is a former senior US government official with two decades of service as an intelligence officer and strategist, including twelve years stationed overseas in the region. He posts as @Mister_G_2 on X.

The Tiger Project, an Atlantic Council effort, develops new insights and actionable recommendations for the United States, as well as its allies and partners, to deter and counter aggression in the Indo-Pacific. Explore our collection of work, including expert commentary, multimedia content, and in-depth analysis, on strategic defense and deterrence issues in the region.

Further reading

Sun, Sep 15, 2024

On the third AUKUS anniversary, a toast to ITAR reform and a call to keep going

New Atlanticist By R. Clarke Cooper

The landmark trilateral security partnership has come a long way, but current reform efforts will only reach their potential if additional regulatory adjustments are made.

Mon, Jun 9, 2025

China is carrying out ‘dress rehearsals’ to take Taiwan. Here’s how the US should respond.

New Atlanticist By Adam Kozloski

With China escalating its operational tempo in the Taiwan Strait, the United States must enhance its forward defense posture in the Indo-Pacific.

Thu, Oct 17, 2024

In a war against China, the US could quickly exhaust its weapons. A new Indo-Pacific defense initiative might be the answer.

New Atlanticist By Adam Kozloski

The new Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience could enable faster provisioning of resources to Taiwan, the Philippines, South Korea, or even the United States if a war breaks out.

Image: ATLANTIC OCEAN (Dec, 6, 2024) U.S. Navy, Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy personnel pose for a picture with Mission Specialist Defender Mark IV remotely-operated vehicles (ROV) and an IVER4 900 autonomous-underwater vehicle aboard the Norwegian-flagged seabed construction vessel MV Island Pride during the Australia, United Kingdom and US (AUKUS) Pillar II Subsea and Seabed Warfare Event Two/Integrated Battle Problem 25.1. (US Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Justin E. Yarborough)