Election season approaches and the effects of Russian information operations are once again manifesting in our government. In February 2020, the New York Times reported that both Democrats and Republicans are already suspicious that the other side of the aisle is benefitting from Russian interference. However, we have overlooked other vulnerabilities in our elections amidst the threat of information operations.

The numerous sectors of our critical infrastructure, to include the elections process, are interdependent on one another and a failure in one sector could result in the failure of another. For example, a power outage would significantly degrade the ability of a small municipality to conduct an election. Recent developments indicate that Russia could exploit the interdependent nature of our critical infrastructure to disrupt our elections via well-timed cyberattacks. How prepared are we to address election interference that goes beyond information operations?

Georgia and others are a testbed for Russian cyber tactics

On February 20, 2020 US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo issued an official statement accusing the Russian General Staff Main Intelligence Directorate’s (GRU) Main Center for Special Technologies (GTsST) of committing sweeping cyberattacks against Georgia last October. Other subordinate units of the GRU, like the unit known to cybersecurity researchers as Fancy Bear, are responsible for infamous cyberattacks like the hacking of the Democratic National Committee in 2016. The GTsST, known popularly as the Sandworm group, “disrupted operations of several thousand Georgian government and privately-run websites and interrupted the broadcast of at least two major television stations.” The cyberattacks against Georgia are an example of how recent forays into other nations have afforded Russia the opportunity to develop new tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) for cyber operations.

Influencing our elections by disrupting critical infrastructure could be a one such strategy employed by Russia in the coming months. Russia has demonstrated its intent to disrupt our democratic processes on numerous occasions in the recent past. Furthermore, the US government has acknowledged that Russia has used cyber operations to gain access to critical infrastructure. Russia would not exploit these vulnerabilities to sabotage financial markets or destroy power plants in the US—scenarios that we typically worry about with nation-state cyberattacks. Severe geopolitical consequences preclude such operations. However, executing limited cyberattacks on critical infrastructure to influence our elections seems like a plausible strategy for Russia given the amount of vulnerabilities that allow them to do so.

United States ill-prepared to address disruptions of election infrastructure

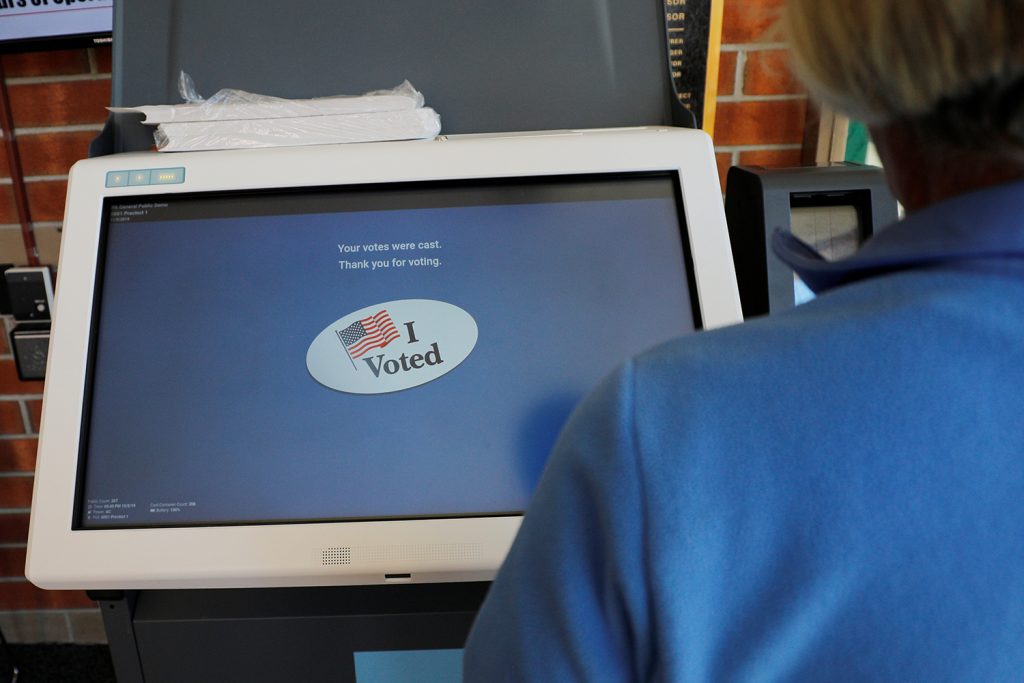

There are three ways that US election infrastructure is vulnerable to Russian interference. First, electronic voting machines are woefully insecure. For the past three years, the hackers at the DEFCON security conference successfully compromised the voting machines typically used in the United States. This year, more than one hundred different machines certified for use in the election infrastructure were exploited and most attacks were described as “trivial.” Sandworm, a group responsible for some of the most destructive cyberattacks thus far like Olympic Destroyer and NotPetya, could easily attack voting machines.

Second, the decentralized nature of US election processes makes regulation and standardization difficult. The power for states to regulate elections is enshrined in the US Constitution and the disparities in election security ranges from average to disastrous. Currently, there are no federal agencies with statutory authority to regulate elections. There are agencies to help along with the process, like the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) and the Federal Election Commission (FEC), but they lack authority to tell states what to do. While the US Constitution does permit Congress to create overriding legislation of elections, the GOP-controlled Senate blocked three election security bills in February, a manifestation of high partisan tensions regarding the election process and a reluctance on the federal level to address the issue. Consequently, the burden of elections security falls on the states, who rely heavily on federal resources throughout the election process.

Third, attackers could leverage the interdependent nature of critical infrastructure to compromise election security through weaknesses in other sectors. Research indicates that many sectors of US critical infrastructure are interdependent and that a disastrous failure in one sector could result in an equally disastrous failure in another. For example, during the Cyber 9/12 event held at the University of Texas at Austin Strauss Center, event organizers asked participants to address a fictional scenario where attackers compromised local power grids to disrupt an ongoing election. Recent events suggest that such a scenario is possible. In March of 2018, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and DHS revealed a “multi-stage intrusion campaign by Russian government cyber actors who targeted small commercial facilities’ networks where they staged malware, conducted spear phishing, and gained remote access into energy sector networks.” These sorts of compromises lend themselves to a situation where threat actors could instead choose to target other sectors of critical infrastructure, like the power grid of a small municipality on election day, to compromise the election process.

The United States is undertaking some measures to address vulnerabilities

Fortunately, there are elements of the US government that have recognized the threat posed to democratic institutions and are acting accordingly. For example, United States Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM) effectively disrupted interference attempts by the Internet Research Agency, Russia’s infamous troll farm, during the 2018 midterm election. This unprecedented maneuver was possible with the recently increased authority granted to USCYBERCOM by the Pentagon. Recent statements suggest that USCYBERCOM is developing a similar strategy for the upcoming election.

On the domestic side, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) within DHS is leading federal efforts to coordinate election security with state and local governments. In the days leading up to Super Tuesday, senior federal officials issued a statement warning the public of potential foreign interference in the primary elections, reassuring that the relationship between federal, state, and local agencies was “stronger than it’s ever been,” according to the officials.

However, the United States may need more than a strong relationship when trust in elections—the cornerstone of US democratic processes—is at stake. Russia succeeded in its mission to exacerbate national divides in 2016 and the consequences have tinted nearly every aspect of political discourse to this day. The government must address three key weaknesses to create a defensible democratic process: election infrastructure security, election law reform, and critical infrastructure interdependency. Failure to address these areas could result in another compromise of US elections and a monumental loss in faith by the public.

Nicholas Cunningham is a cadet at the US Military Academy and a member of BlackJacks, the winning team at the 2020 Cyber 9/12 Strategy Challenge in Austin, Texas.

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect the position of the United States Military Academy, the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Image: The screen reads "I Voted" after a voter went through a practice session with the new Election Systems & Software ExpressVote XL voting machine, an electronic voting system with a backup paper trail, in Hanover Township, Pennsylvania, U.S., October 5, 2019. Picture taken October 5, 2019. REUTERS/Brian Snyder